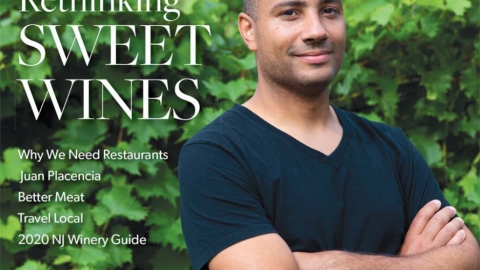

Juan Placencia Starts Over Again

“It’s happening,” says Juan Placencia. “Everything is moving fast.”

Placencia, a revered and beloved chef known in New Jersey as much for his ceviche as his ambition, spent the summer of 2020 being whisked to impromptu business meetings in Brooklyn, Manhattan, Montclair, Philadelphia, Chicago. His top-tier business network includes experts from all aspects of the hospitality industry—people who have consistently squeezed success out of withering situations, despite strangling rents, despite the increasing difficulty of finding and keeping staff, despite an aloof, fickle, and demanding customer base.

And then came the pandemic, making the difficult impossible. If you’re in the restaurant business today, says Placencia, you’re either on a thread or in the red. Everyone is scrambling to find a way out.

“I wonder if this is how prospectors felt during the American Gold Rush—seems like everyone is working on striking gold.”

In August, Placencia signed a lease to operate a ghost restaurant in Philadelphia; he expects to be up and running by the end of September. A ghost restaurant, a concept gathering steam in Silicon Valley and now on the East Coast, offers delivery only, eliminating the need for a dining room, tables, or wait staff. Placencia is acutely aware of the risk; in America, dreams can be snuffed in an instant, he says. On the other hand, he’s working, he’s moving. “It’s a thrill for me,” he says. “An opportunity to get scrappy again.”

In many ways, Placencia has been an avatar; his story is the story of the evolution of the immigrant in America and of the evolution of family restaurant to business empire. Placencia’s parents are from Peru, and Placencia began his culinary career as a child working in their North Jersey restaurant. He expanded his expertise at culinary school and by working in several of Manhattan’s most important kitchens. He opened a small restaurant in New Jersey, then a larger one. Yet success was a veneer. In reality, Placencia had lost everything before the pandemic. He already knew the center couldn’t hold.

A ghost restaurant is perhaps an apt and bittersweet name for a business hoping to emerge amid the wrath of Covid-19. But Placencia doesn’t have time to deliberate the symbolism.

“The restaurant business, as it was, is over. Not forever, but it’s over for now. We are forced to move into the future. Either you get on the train or you don’t. We’ll see what happens when it happens.”

Placencia was a toddler when he arrived in New Jersey in 1984 with his parents, Willy and Ana.

“THE RESTAURANT BUSINESS, AS IT WAS, IS OVER. NOT FOREVER, BUT IT’S OVER FOR NOW. WE ARE FORCED TO MOVE INTO THE FUTURE. EITHER YOU GET ON THE TRAIN OR YOU DON’T.”

A Culinary Education

Placencia was born in 1982 in Lima, Peru, home of the Pisco Sour. In Lima, the day often began with a trip to the Mercado, a thrumming open-air market, vivid and noisy—a place to buy whole chickens and fresh-caught fish, purple-hued potatoes, and jugo surtido, a juice made from an assortment of fruits, freshly pressed, usually containing strawberry, banana, papaya, and sometimes pineapple. For Placencia, a good day was one that began with yuquitas, a deep-fried dough—think of a yeast-risen doughnut without glaze, says Placencia—sold at a popular stall. You had to arrive early; sales ended when the yuquitas were gone. “By 11 in the morning, the shop was closed,” says Placencia. “They were done for the day.”

In Peru, 1980 began an era of internal brutality that would last two decades, marked with massacres and human-rights violations. Thousands migrated and more than 70,000 people died or disappeared. Many Peruvians came to New Jersey, settling in Paterson, Newark, Harrison, and Kearny.

Placencia was a toddler when he arrived in New Jersey in 1984 with his parents, Willy and Ana. They joined others in the family—Placencia’s paternal grandmother, Olga, had made her way to the States years before. “She was looking to restart her life.”

Today Placencia defines immigration not as a crossing but as a trek. His family, like so many others, was led to America by a coyote. The Placencias were warned about their talkative child; if the boy couldn’t keep quiet, the family would be left behind.

The Placencias lived first in Jersey City. In 1987, Placencia’s brother, Jonathan, was born. In 1989, the Placencias opened San Andres restaurant, with 60 or so seats, one of two Peruvian restaurants in Hudson County. They served ceviche, and dishes made with Peruvian staples such as choclo (Peruvian corn) and potatoes (Peru is home to 3,800 varieties of potato). The restaurant became a hub for fellow Peruvians and, as its popularity grew, for the larger community.

As the son of restaurant owners, Placencia’s childhood was one of full bellies and succulence—killer rotisserie chicken, ceviche (“always, always ceviche”) and papa la huancaina, boiled potatoes, sliced in discs and served with a creamy yellow sauce made with queso fresco and aji amarillo (yellow Peruvian peppers). Placencia and his brother were immersed in the family business. For both sons, Juan as chef and Jonathan as business partner, the industry provided sustenance and opportunity. “I began my restaurant career when I was 6,” says Placencia.

As a child, Placencia sought library books on butchering. By age 10, he was making omelets and pancakes for family brunch. “I was the kid who was more enthused about Sunday morning cooking shows than Saturday morning cartoons,” he says. He watched Julia Child and Jacques Pepin. At the end of each school year, Placencia was sent back to Peru to stay with his mother’s family. In Lima, he lingered often at his aunt’s restaurant, a party space with 350 seats, and he continued—with his cousins and aunts—his daily ritual at the Mercado Cooperativo Balconcillo, better known as the Mercado Palermo.

In New Jersey, the Placencias opened a new restaurant in 1998 named Oh Calamares! in North Bergen; the restaurant moved to Kearny in 2003.

As an adult, Placencia furthered his education with a degree from the Culinary Institute of America and worked in the kitchens of some of the finest restaurants in New York City, including Gramercy Tavern and Eleven Madison Park. At Jean-Georges, a temple of haute cuisine, Placencia learned the secrets to tuna ribbons, seared scallops with roasted cauliflower, and the restaurant’s signature molten chocolate cake—dishes that were among the most talked about and most photographed in the world. Also at Jean-Georges, Placencia learned to look at cuisine through a global lens, marrying this ingredient to that technique, combining the expertise of cultures and recipes worldwide. And he learned the layers of discipline that are required for consistency. “At that level, perfection is the only option; there is no room for error.”

In 2010, Placencia channeled all that education and energy—all those rustic Peruvian family recipes with that haute cuisine expertise and discipline—into Costanera, a 60-seat restaurant that he opened, as an extension of the family business, on Bloomfield Avenue in Montclair. Costanera consistently received stellar reviews— from The New York Times, The Star-Ledger, Inside Jersey magazine, New Jersey Monthly.

Success was a slow climb—the state’s economy was still weak in the aftermath of the housing collapse in 2008 and Costanera had no liquor license—but in 2018, Placencia was ready to make his big move. He opened Somos in North Arlington, a pan-Latin restaurant that was also an event space and, at night, a dance club, with 6,000 or so square feet [see “Story of a Dish,” Edible Jersey, Fall 2019]. Placencia, stretching, was eager to leverage the family business. In America, he says, bigger is better. More is better.

As the decade approached its end, and as Placencia neared his 40th birthday, everything seemed to be in place. Placencia was happily married with two young daughters, and photos of his family, charming and giggly, fill his cell phone. He had become a well-regarded restaurateur, counting among his friends and colleagues some of the most esteemed names in industry. He had turned the family business into a burgeoning empire.

Yet Placencia could not sleep. He was not able to shut down his brain, and couldn’t escape from his dark thoughts. “I couldn’t find any respite—no moment of tranquility or peace.”

In Peru, family is foremost, a philosophy illuminated in a variety of ways but uniquely so by the nation’s cultural affinity for godparents. The designation—godmother, godfather—is not just a sacrament of the church. Peruvian children have any number of godparents. In Peru, you have your immediate family, which you nourish and nurture, and then you add to that family by naming godmothers and godfathers for just about every occasion, for any ceremony, pulling in as many supporters as you can.

“We have each other’s backs,” says Placencia.

In New Jersey, a fine example of this tradition comes directly from the work of the Placencia family. Placencia’s mother, Ana, helped start the Peruvian Civic Association of New Jersey, which promotes Peruvian and Latin American culture—art, music, literature, and food. The organization sponsors an annual Peruvian Independence Day Parade in July, from Harrison to Kearny, a commemoration of Peru breaking free from Spain in 1824. The civic association is a source of community pride, and food is a critical element at any event. “All Peruvians say we’re the best cooks in the family,” says Placencia. “We have the best food on the planet.” Bragging rights aside, Placencia has a point. Peru is one of the most biologically diverse countries in the world, home to 25,000 plant species.

The Peruvian Civic Association designates, among its office holders, additional titles, including international godmother and artistic godfather. Such designations reaffirm civic ties.

“The titles of padrino or madrina, comadre or compadre, carry significant honor and responsibility,” says Placencia. “In Peruvian culture our godparents wear badges of wisdom, loyalty, and selflessness.”

Yet internally, within the Placencia family, as the businesses expanded, battles escalated. The family argued about financial priorities, about staffing, about the type of late-night entertainment to offer. Last year, the brothers stopped talking to each other. Placencia still isn’t sure the relationship can be repaired. Reflecting, he is blunt. He had been unable to delegate. He was blind to the fact that he was attempting to superimpose an escalating business model—Somos is a party and event space—onto a small restaurant business. Scaling up had overwhelmed the operation, and staffing issues, common to the industry, had exacerbated the problems.

Family has the power to love and destroy in profound ways. For Placencia, the pressures of the restaurant business had created a compression. And for the child of immigrants, one who grew up with heightened cultural expectations, that compression began to feel like a vise.

“Whether we were born here, like my brother was, or brought here, like I was, our parents are living their American dream through us.”

In general, second-generation Latinx immigrants earn more money and are better educated than their parents. Yet those benefits appear to come with a price. Researchers have long studied the Hispanic Paradox: the fact that Latinx in America enjoy higher life expectancies than their counterparts, no matter their socioeconomic status or level of education. “This survival advantage, which has been noted for the past few decades, is most pronounced among Latino first-generation immigrants,” reports researcher Noreen Goldman of Princeton University, a professor of demography and public affairs, in an interview published on the university’s website.

Researchers also have discovered a paradox within the paradox, as notes Nicholas Kristoff in The New York Times. “First-generation Latino immigrants tend to live longest, and their children— while better educated and earning more money—die earlier.”

The reason? Kristoff offers a summary. “Part of the explanation may be that what many white Americans think of as ‘traditional American values’— an emphasis on faith, family and community ties—are disproportionately found among Latino immigrants, but then fade as their children assimilate.”

Strong cultural ties can be a double-edged sword, says Placencia: “As tight-knit as the community may be, it can also be a little coddling.”

Fearful of the thoughts that now consumed his days, Placencia sought psychiatric help. He determined that the family restaurant business was destroying his relationship with his family, and he decided to disentangle himself from the business. Restaurateurs are known for their decisiveness, for better or worse, and, once his decision was made, he acted quickly. Earlier this year, he announced his plans: He would sell Somos, and he would transfer Costanera to his chef de cuisine. In February he closed both restaurants. “Money comes and goes, right?”

When Covid-19 hit—a sudden shift and great rupture—Placencia was grateful that his own great reckoning already had occurred. Had his path not previously split open, who knows?

“I probably would be very lost right now.”

FOR PLACENCIA, THE PRESSURES OF THE RESTAURANT BUSINESS HAD CREATED A COMPRESSION. AND FOR THE CHILD OF IMMIGRANTS, ONE WHO GREW UP WITH HEIGHTENED CULTURAL EXPECTATIONS, THAT COMPRESSION BEGAN TO FEEL LIKE A VISE.

An Awakening

For his spiritual journey back, for his reclamation of his cultural values, Placencia thanks his chef de cuisine, another immigrant.

Walter Ajquijay was born in Guatemala, one of nine siblings, into a village outside Guatemala City so poor that most of its residents didn’t have shoes. Ajquijay came to the United States 11 years ago, and for the past six years he’s worked in the kitchen of Costanera in Montclair. Ajquijay is quiet, hardworking, religious. On weekend mornings, he plays soccer. Placencia admired him immediately. Ajquijay and others from his village, who now live in New Jersey, Canada, and Europe, pool their resources and send money back home.

“A dollar goes a long way in Guatemala,” says Placencia. “When you are sending hundreds of dollars a month it’s like hitting the lottery.”

Placencia, who closed Costanera in February, had arranged for Ajquijay to take over the restaurant. As part of the process, Placencia flew to Guatemala in January to meet the family. He believes business should be conducted in person. “I wanted them to know that I wasn’t trying to scam anyone.”

For Placencia, that trip to Guatemala was a spiritual reckoning, and solidified his resolve to do what he had planned to do.

Placencia planned to shepherd his restaurant through its next stage, through a financial commitment to Ajquijay and Ajquijay’s business partner Monica Mata, by staying on as a consultant. In putting together their business plan, Placencia, Ajquijay, and Mata did what many Latinx do: They leaned on each other.

Carlos Medina, president of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of New Jersey, says access to capital is the biggest problem faced by Latinx businesses. In New Jersey, more than 120,000 business are Hispanic-owned, and those businesses contribute $20 billion annually to the state economy. Medina has worked to build awareness and combat institutional lending discrimination against Latinx business owners, and last year formed a partnership with World Business Lenders in Jersey City in an effort to make more funds available to Hispanic-owned small businesses. In April, he launched a television series on Univision in part to help Latinx business owners navigate the economic crisis brought on by Covid-19.

Ironically, their biggest asset has been thwarted. “The superpower of Hispanic business owners is that they’re very social,” Medina has said. “So, we always encourage them to use that superpower, because they network well.”

At Costanera, Ajquijay and Mata signed a five-year lease. Their first day as restaurateurs was March 1, 2020. They marked the occasion by getting right to work.

On March 15, they closed the restaurant, following Gov. Murphy’s statewide shutdown orders. Later that month, Ajquijay’s temperature spiked. Placencia drove him to the hospital, but Ajquijay, a young man with no underlying health conditions, was rejected for testing several times by a healthcare system that was overwhelmed. His fever lasted days, hovering at 104 degrees. Finally, Ajquijay was administered a test, which proved positive, and he was treated at Mountainside Medical Center in Montclair. Once he was released, his community rallied in support, and members of his church, the Emanuel Church of God in Montclair, delivered food and necessities to his home. His recovery was tedious. He lives with six people; of those, four were infected with the virus, and each infection reset the two-week quarantine clock.

Ajquijay is healthy now, as are his roommates. But his plans have changed. Costanera is over, and Mata is pursuing a different career. And, in this time of Covid-19, economic upheaval, and civil unrest, Ajquijay has had enough of America. He will return to Guatemala as soon as the risk of travel—of the possibility of transmitting the virus to his village—is gone. “I get the sense that he is disenchanted with the American dream,” says Placencia. “I don’t think he sees that bright future that he saw at one point.”

In Guatemala, the money Ajquijay sent home lifted his family out of a cycle of poverty. The family bought land. They launched an agribusiness, and they now grow and sell flowers. They built a bigger home. Ajquijay himself has a newly constructed house, nearly finished, awaiting him.

Placencia, in many ways, is jealous. “I kind of wish I was Walter.” If possible, Placencia plans to accompany Ajquijay on his journey home, to witness the family reunion, but also for the restorative experience. Placencia is eager to return to Guatemala. “I have cooked for, and waited on, heads of state, celebrities, royalty from other places in the world. I have never been star-struck, never had sense of awe. But with them, I was humbled by the entire experience. They have a regal air,” says Placencia.

Their village is verdant, says Placencia. Fresh air and crystal-clear skies day and night. Dinners were simple—homemade tortillas, for example—but the lettuce tasted like lettuce and the onions tasted like onions. “As if I had never had them.” The larger, newer family home remains humble, with no indoor plumbing and a frugal and intentional approach to electricity. The home is four expansive rooms, hacienda style, with a courtyard. The house sits atop a hill, with a view of the surrounding hills, where the wilderness is buttressed by parcels of land that have been cultivated, irrigated, tamed. Placencia remembers a night, after dinner, where, inside the home, a breeze blew through the open windows, a chilly breeze, he says, 50 degrees, but not a chill that penetrates the bone. The air was an awakening, like a first breath. “It was almost like I went to a completely different planet,” he says. “Earth, Day One.”

Placencia was most inspired by Ajquijay’s mother, a serene woman with a piercing gaze and unwavering faith, no matter the severity of the circumstances. “She is the rock of rocks. If I can have a fraction of what she’s got, I think I’ll be OK.

“They reminded me of my family, my lineage; in Lima you see that mestizo, that aesthetic. The clothes they wear—even though the embroidery is different, the patterns are different and the fabric is different, the colors were the same. The colors were just as bright.”

Each day in Guatemala, Placencia awoke early, at the crow of the rooster.

“I prayed when I was there. I’m not very devout but I was raised Catholic. I think I did some of my best praying on that land.”

“I’VE ALWAYS LIVED IN A VERY DEVELOPED PART OF THE WORD. I KNOW MORE ABOUT TELEPHONE POLES, ELECTRICAL POLES, THAN AMAZING FOLIAGE AND FAUNA. THAT’S WHAT I’M SEEKING IN THE LITERAL SENSE. NATURE. MORE NATURE.”

The Evolution

Placencia uses a cooking metaphor. This reckoning, he says, is like cutting through the fat, the act of taking a rich dish and tempering it with acid. The pandemic is forcing needed change, both in his personal life and in the industry.

At home these past months, Placencia has been cooking for his family, everything from scratch. He’s lost weight, feels more energetic and healthy. He’s naturally eating less meat, drinking less alcohol. “I have family. I have food. I’m OK. I have a roof over my head.”

When he wants to cook something on the grill, he burns apple wood, cherry wood. The smells remind him of the wood-burning stove at Gramercy Tavern, a New York City restaurant dedicated to seasonality, to New American cuisine, and to a thoughtful rusticity. Gramercy Tavern offers a connection between Old World and New World. The musky smolder of burning wood also takes Placencia to Guatemala.

He thinks often of Guatemala. “They don’t value money the way that I had,” he says. Yet he witnessed, among the Ajquijay family, a higher level of security, more serenity, a way of life that’s now sustainable. “They’ll always have something to eat. They’ll always have the resources to put a roof over their head. They were never starving, and they certainly were not starving in the spiritual sense.”

He thinks about self-sufficiency. Is it possible to collect rainwater for home use? Is it possible to turn his backyard into a small farm? Is it possible to homeschool his girls?

“I’ve always lived in a very developed part of the word. I know more about telephone poles, electrical poles, than amazing foliage and fauna.”

He goes hiking, and takes along his older daughter. Perhaps someday he’ll buy his own cabin in the woods. “That’s what I’m seeking in the literal sense. Nature. More nature.”

He worries, once the threat of the pandemic is over, that Americans will quickly return to a toxic and greedy lifestyle, eager to consume, but also eager to find a bargain— the kind of mentality that is anathema to a small business or a local restaurateur, businesses that cannot slash costs because of sales volume, businesses that are more about authenticity than price. Americans do not prefer to shop daily at the Mercado, he says. Even in the ‘80s, he and his family were shopping at Woolworth’s.

And yet, as Placencia has proven again and again, a neighborhood restaurant, one with a budget-conscious approach and one that is responsive to the community, can survive and thrive. Placencia still helps out in the family business in Kearny as needed. Oh Calamares! continues to evolve, and the city’s newest residents, who are Chinese and Indian, appreciate the bold flavors of Peruvian cuisine. Meanwhile, the restaurant returns the compliment, adding Asian influences to its menu.

These days, Placencia and his brother are civil to each other. This summer, his brother became a father again, and Placencia is hopeful that another baby in the family will be a source of joy.

A Pisco Sour has its complexities. The cocktail begins with pisco, a distilled brandy made from grapes, plus lime juice, egg white, and bitters. The origin story of the Pisco Sour is disputed— Chileans also lay claim to its creation, yet most historians attribute the drink to an American bartender, Victor Morris, an ex-pat in Lima during the 1920s. The Placencias have served their share of drinks made with pisco—the menu at Oh Calamares! alone includes a dozen or so options. But the Pisco Sour is unique, a cocktail that combines the terroir of Peru with the inventiveness of an American. A Pisco Sour is earthy, sweet, and tart.

A chef—and an immigrant and an American—is always thinking about evolution, about starting over.

“Having the opportunity, no matter how big or small it may be, to help shape the next chapter in the restaurant industry, that’s amazing.

“It feels good to be moving.”

GOING FORWARD

Chef Juan Placencia says it’s no longer possible to do what his parents did: come to America and build a life based on a brick-and-mortar restaurant, feed a community, and become successful. To do so, you need funding, investors, access to wealth.

A ghost restaurant, however, requires less capital.

In October, Placencia is scheduled to open what he anticipates as the first of several ghost restaurants. Brazas, featuring Peruvian wood-fired rotisserie chicken, will operate in Philadelphia’s University City (home to the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University, among others).

Under the Somos Hospitality brand, Placencia plans to launch additional restaurant and consulting operations. His restaurant space in North Arlington remains for sale.—T.P.