Rain Gardens

After a week of heat, humidity and sunshine, a good heavy rain is a welcome relief. But what happens when the downpour ends? Just the other day, I watched helplessly as a broad stream of silty runoff gushed down the curb. Barren dirt from my neighbor’s front lawn-in-progress had eroded in the storm, picking up road oil, grease and stray garbage on its way to the storm drain and the nearby Whippany River.

“We treat water like garbage,” says Jared Rosenbaum, owner and botanist at Wild Ridge Plants. We let it stream down our dirty streets and into the sewer system, instead of collecting it as the critical resource that it is. But how do you catch rain? Yes, there are rain barrels, but they only do so much. Installing a rain garden is a natural, beautiful way to keep the rain where it falls, precisely where it can do the most good for our environment.

Why rain gardens? Rain gardens perform important services for the ecosystem, including replenishing groundwater, removing pollutants, and much more. When you help the natural environment, humans benefit, too.

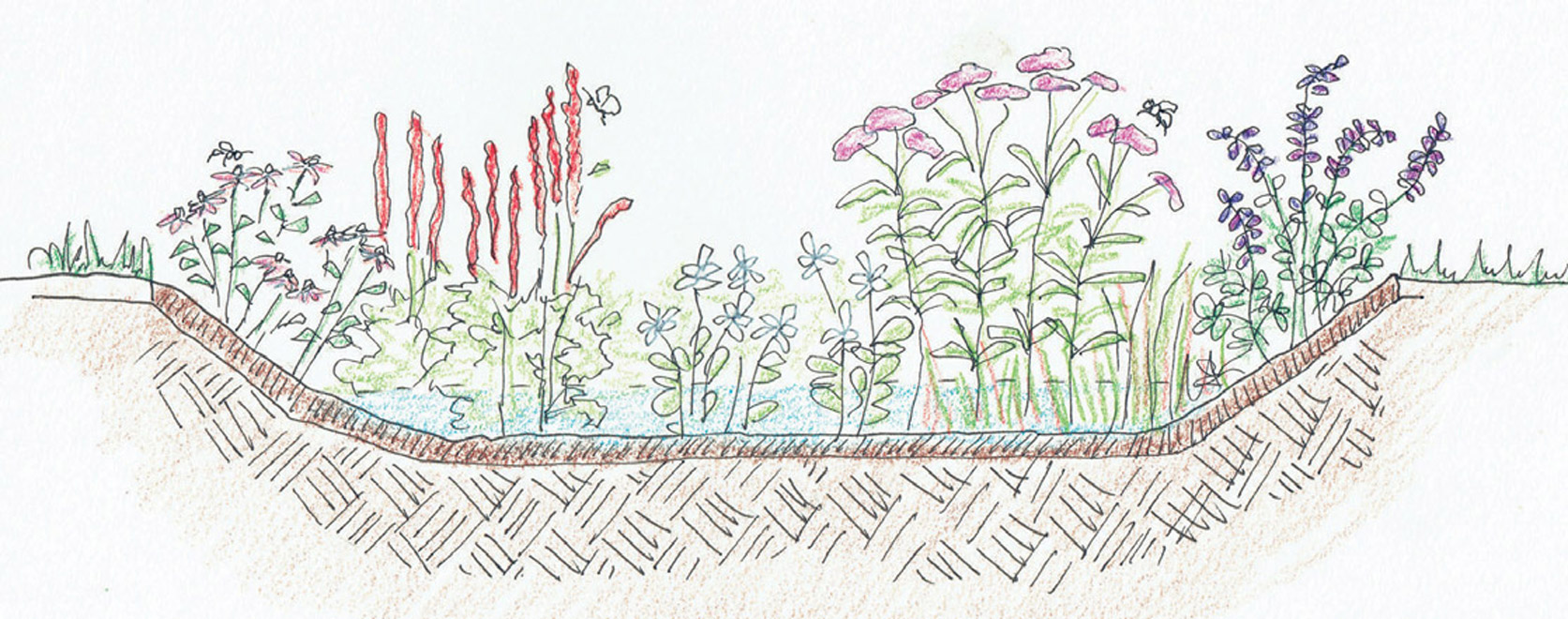

What is a rain garden? A rain garden is as simple as a depression in the ground. It collects rainwater and allows it to soak into the earth before it gets into the storm water system. A rain garden is typically 6 to 12 inches deep. This depression is planted with native plants that evolved in this region and flourish in our wet springs and dry summers. Native plants typically have deep root systems and can reach water even in summer. These long roots also act as conduits to get the water into the ground. Rain gardens are planted mostly with perennials that die back in winter, and about one-third of their roots die back too, leaving little tunnels for water to travel down. So, as these native plants establish themselves, a rain garden will start to drain even faster.

Rain gardens are typically wet for fewer than 24 hours after a rain—not long enough for mosquitos to emerge. Rain gardens can endure long periods of dry conditions. The best rain garden plants are not wetland plants, but plants that can tolerate wet soil for short periods and thrive in dry summers as well. Sedges, Joe-Pye weed, swamp milkweed and swamp mallow are all excellent examples.

Installing your rain garden. Make sure the area you choose is downhill from down spouts, but not in a saturated area. Your rain garden should be 15 feet away from a basement wall, 10 feet from a slab. To make sure you’ve picked the right spot, do an infiltration test by digging an 18-by-18-inch hole. Fill it with water, let the water soak in, then fill it again and wait for 24 hours. This will tell you if you have good infiltration or not. A good location will drain in 24 hours. If not, you can amend the soil with sand and organic matter. If it is draining well, don’t do too much. You do not need well-tilled, fertile soil for native plants.

Once you have dug out your rain garden, it’s time to plant it. Plant it fuller than a perennial garden, so it fills in quickly. Using landscape plugs can make for an easier and less expensive rain garden. A landscape plug is a well-rooted plant often sold in flats of 50. A full planting mimics nature better and reduces the space for weeds to invade. It is also better to plant in masses, at least five of each perennial or grass—though 20 is better, since any weeds will be easy to distinguish and make maintenance easier.

Maintenance. Maintain your rain garden just as you would any other garden. Water as necessary through the first two seasons while the plants establish. Use no chemicals, herbicides or insecticides, as these would contaminate the rainwater you’re trying to purify. Lightly mulch until the garden becomes too full to need mulching.

Your rain garden will also help you create more biodiversity in your yard, which is the best way you can help our declining bird and insect populations.

With residential landscapes occupying almost one-fifth of the entire United States, what we do in our own yards has a huge impact on the health of our planet. It rains about 46 inches per year in New Jersey. Most of that runs off into storm drains. If everyone installed a rain garden, just think of the difference we could make.

For more information and a list of appropriate rain garden plants, check out this Rutgers University site: Water.Rutgers.edu/Rain_Gardens/RGWebsite/raingardens.html

4 ECOSYSTEM BENEFITS

PROVIDED BY A RAIN GARDEN

Groundwater replenishment: More than one-third of Americans get our drinking water from groundwater, so it is important to let rainwater get into the ground, instead of sending rainwater directly into the storm drain on the street.

Pollutant elimination: When rainwater runs off hard surfaces like roofs and driveways, it collects pollutants, oil, fertilizer chemicals and more. The runoff ends up in nearby steams and ponds, causing water pollution. This is part of the reason we saw a harmful algae bloom in our large lakes last summer, which halted swimming and boating. Up to 70% of the pollution in our lakes and streams is from storm water runoff. Excess nutrients in the water cause a dense growth of plant material on lakes, which in turn uses up the available oxygen in the water and also blocks the sun. In these conditions, aquatic life starts to die. The top 12 inches of soil in a rain garden acts as a giant filtration system, removing pollutants from the water physically, chemically and/or biologically. A rain garden can reduce water pollutants by up to 68%.

Prevention of downstream flooding: As storms get more frequent and drop more water due to climate change, we will see more flooding than ever before. Imagine if even half the 3,000 owner-occupied homes in Morristown installed rain gardens in their front yards. Each garden could store 1,120 gallons of water. If 1,500 rain gardens held 1,120 gallons each, then 1,680,000 gallons of water would not reach the Whippany River and overflow its banks. Now, multiply that by the number of towns along the Whippany River. By installing rain gardens, we could see real change.

Replication of natural systems in our home gardens: By trying to mimic what rainwater might have done on our properties before development, we let the water get back into the ground. Not only do we “do no harm,” but we repair some of the harm that was done in the decades before we bought our homes.