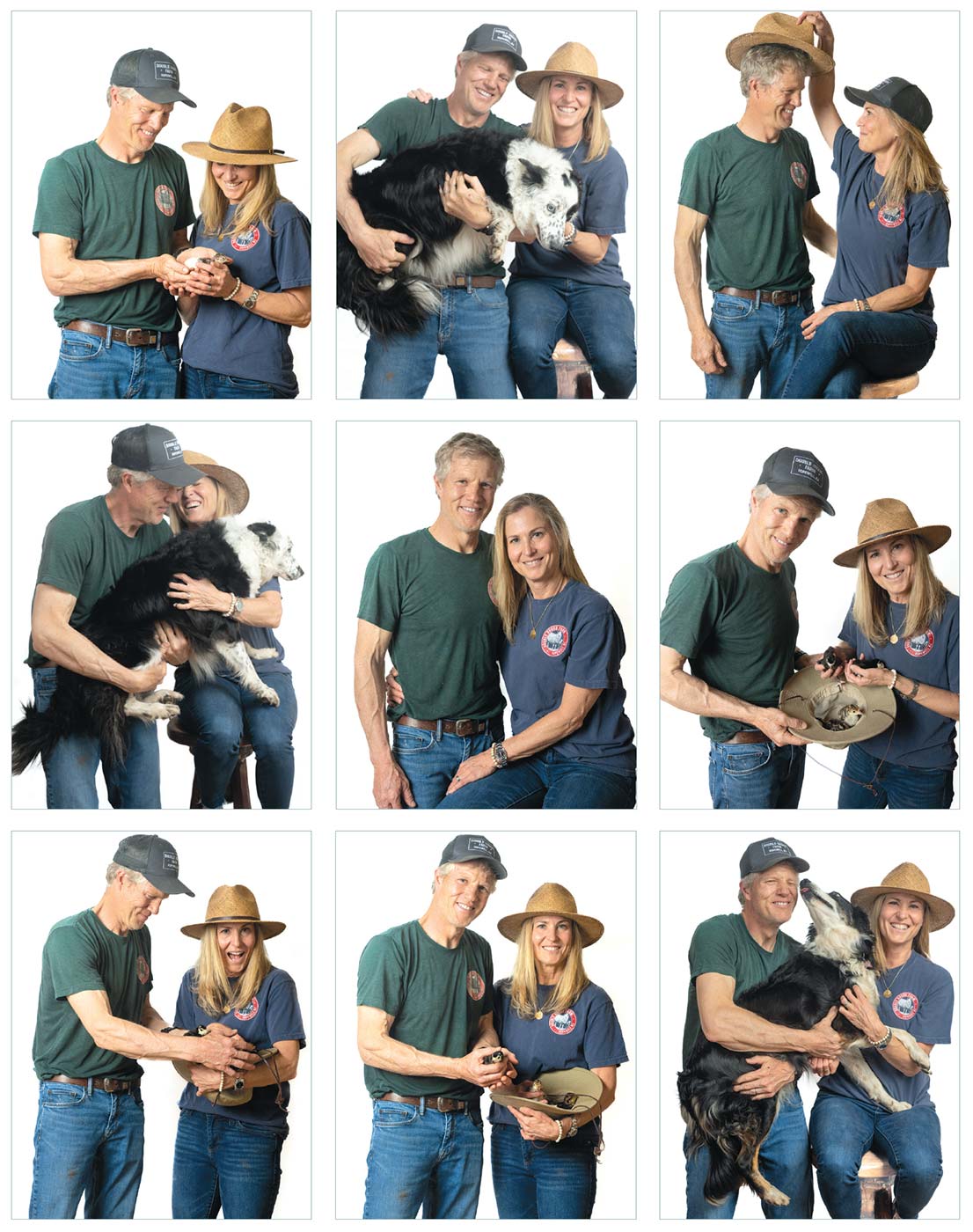

Robin & Jon McConaughy: Double Brook Farm

“WE WANT TO TAKE WHAT WE LEARNED OVER THE YEARS AND SHARE THAT KNOWLEDGE TO BENEFIT OTHER FARMERS.”

Can a magazine article change your life? In the case of Jon and Robin McConaughy, one at least jump-started a directional change for them and their young family that led to their establishing Double Brook Farm in Hopewell in 2004.

The article was “Power Steer” by Michael Pollan, best known as the author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, which famously explored our food sources and choices. It was the New York Times Magazine cover story that week in 2002, when Robin read it. She passed it along to Jon, and in Robin’s words, it “opened our eyes” as to how meat was raised and processed.

Today, the McConaughys own and manage 800 acres on which they raise pigs, sheep, lambs, turkeys, and chickens. Over the ensuing years since starting Double Brook, they also established and operated Brick Farm Market and Brick Farm Tavern in Hopewell. Their meat and poultry products were on the shelf and menu at those venues as well as other select quality grocers and restaurants. The McConaughys have also served as partner and advocate for other area farmers and Jon has often been a spokesperson at various forums, on behalf of sustainable and humane animal farming practices.

Now, two decades in, they have moved out of restaurant and food market ownership but are launching new plans and expanding existing ones, not downsizing but refocusing.

Edible Jersey: This all started because of a Michael Pollan article?

ROBIN McCONAUGHY: We bought this piece of property and had just moved to New Jersey full time, and I had read [the] excerpt in The New York Times Magazine from Michael Pollan about commodity beef. I said to Jon, “Read this. It’s going to totally turn you off. Or it’s going to open your eyes.” We like eating meat, so that planted a real seed. And in fact, Jon continued to read a lot of Michael Pollan, Joel Salatin, and Greg Judy, about how to raise animals so you can feel good about what you’re eating.

And our kids were little. They were literally just a few months and 2 years old. We wanted them to eat healthy food. We wanted them to also know where their food was coming from. That felt important.

EJ: Over 20 years, a lot has changed. You seem to have come more into focus and alignment. We are all geniuses in hindsight, but before discussing what you are doing differently now, what would you have done differently?

JON McCONAUGHY: When you think about farm-to-table and you ask people to say what that is, it’s a carrot, or it’s an onion, or it’s lettuce, or it’s microgreens. And then if you say, “Well, OK, what did you have for dinner last night?” And it’s a pork chop, or it’s chicken. What we think is our meal is defined by the center of the plate, but what we think is local is defined by the edge of the plate. Raising specific center-of-the-plate proteins and bringing more attention to how we do it has been a big part of our journey.

In the beginning, we were trying to produce everything: animals, vegetables, and much more. We tried to make cheese, we made ice cream, we had bee boxes for honey. Over time, our focus became the meat animals because they are more complicated and more important to get right. Every herd is a separate business. Each business is its own, its own animal. [laughter]

EJ: What is important here at Double Brook is the entire lifespan of your livestock, from birth to slaughter. You did a lot of reading, research, and experimentation.

JON: We also just dove in and we learned a lot. We’ll probably always be learning. That’s what I like to do.

We look at the entire picture. It’s not just how the animals are harvested, but how they’re born, how they’re raised, how they make it to the slaughterhouse. We have such a high-touch operation. We eyeball every single animal every single day, and we have thousands of them.

We care about animal welfare and the impact on the environment, and that’s part of what people are paying for when they buy our meat. They’re paying for our animals not to be a widget. They know where the meat comes from, not relying on some general “raised in the U.S.” label. They know that the farmer knows the animals and they are being led to slaughter by that farmer.

This is a unique aspect of us. It wasn’t initially by design, but we’re the only slaughterhouse in the country where the animals walk to the slaughterhouse right from the farm instead of being trucked in.

“[OUR ANIMALS] ARE ALWAYS WITH THEIR SOCIAL GROUP. THEY’RE ALWAYS WITH THE FARMERS THEY KNOW. THEY’RE IN A FAMILIAR ENVIRONMENT BECAUSE THAT’S WHERE THEY WERE BORN AND RAISED.”

EJ: There are other unique aspects to your operation, for which you even consulted Temple Grandin, renowned advocate for the humane treatment of livestock. One hears horror stories about the large-scale processing of meats in this country, but your space is pristine, no foul odors. It even seems serene.

JON: We are one of only two on-farm USDA-inspected slaughterhouses in the country. To sell meat retail, the process has to be USDA-inspected. No way around that. We have to schedule inspectors and provide office space for them, too.

Since there are only two such slaughterhouses in the entire country, what that really means for 99.9999% of the protein that we’re eating is that the farmer loses control in the transporting of the animals at [what is perhaps] the most important time. So, it becomes less personal right off the bat and becomes much more transactional.

And how we slaughter was very important to us from the beginning because we could control how our animals are treated until the final moment. That was the impetus for us to get into it, and our experience over time has confirmed that it was the right choice to build our own processing facility.

Our animals never get on a trailer. They are always with their social group. They’re always with the farmers they know. They’re in a familiar environment because that’s where they were born and raised. Plus, the reduced stress of our animals has an impact from the perspective of flavor. You can taste the difference.

EJ: Jon, you worked on Wall Street for many years as a trader. I am watching you crunch numbers in your head as we talk, but some of these decisions were clearly not based on P&L solely but by events outside your control, like the unexpected death of Richard Moskovitz, your partner and highly respected general manager of the Brick Farm Tavern and Market operations. Did that push you in a different direction?

JON: We were already working seven days a week, 16 hours a day, because of the pandemic. And then Richard passed away unexpectedly. We didn’t have to worry about those retail operations with him at the helm. It was, like, “He’s got it. No problem.” But then we suddenly had to again, and they are totally different businesses than the ones we were focusing on.

EJ: But out of tragedy came something fortuitous: a relationship that had already been formulated with Otto and Maria Zizak.

JON: Otto and Maria are restaurateurs who moved here from Brooklyn and they’re neighbors, with their farm abutting ours. We already had a great personal and business relationship with them. Shortly after Richard’s death, we spoke to Otto and Maria.

The initial idea was another partnership, but Otto preferred full ownership. That was fine with us. The agreement we reached was for them to have a stake in the farm, and we retain a stake in the retail operation. It has been enough glue to tie this all together, but also made sense from the perspective of the direction we wanted to take.

EJ: What does the future hold for the McConaughys and Double Brook Farm?

ROBIN: We’re getting ready to open up direct-from-the-farm operations focused on traditional animal shares and bulk orders. Single cuts and various cuts to order will still be available at the new retail shop, The Brick Farm Butcher, which opened in December of 2023, adjacent to Brick Farm Tavern, now owned and operated by the Zizaks.

One of the things the pandemic did was take away our experiences. Now that we’ve been freed up a little bit, I think we want to get back into doing farm tours. We have always enjoyed educating people about what we do, what makes us different. When you’re raising protein, people don’t think of it as a farm, per se. They think of fruits and vegetables and pick-your-own. If you can bring the experience back so that people aren’t just going out of their way to pick up a dozen eggs, but because they want to learn more about how we farm, it becomes more personal. They see farming happening on a craft level versus commodity level.

EJ: Robin and Jon, clearly, your commitment has not waned and you are both still all in. One more project worth mentioning is your foundation. What is the focus there?

JON: We want to take what we learned over the years and share that knowledge to benefit other farmers. How to get better access to capital. How to do more on-farm processing and find more straight-to-consumer pathways, which keeps more money in the farmer’s pocket.