Immigrants and Restaurants

NJ chefs and restaurant owners react to policy changes and reflect on the importance of an immigrant workforce

Few sectors of our economy rely on immigrants more than the food industry, especially in New Jersey. Migrant workers have harvested the Garden State’s crops for decades. Restaurants rely on immigrant cooks, servers, dishwashers and chefs. Opening a restaurant or food market is a common way for entrepreneurial immigrants to become small business owners. According to Maria Nieves, President and CEO of the Hudson County Chamber of Commerce, the vast majority of the restaurants she represents are family-owned by first-generation immigrants.

“The service industry needs a workforce,” says Chef Anthony Bucco, who has led numerous top New Jersey kitchens.

“Immigrants are simply looking for work. No one arrives in this country dreaming of being a line cook or a dishwasher.

Working in a restaurant means long hours of physically demanding work in difficult conditions.

“People come to the United States for an opportunity for a better life. Restaurant jobs become a viable option for many immigrants. The opportunities are numerous. And, in most cases, challenges with language and communication don’t present issues in a kitchen.”

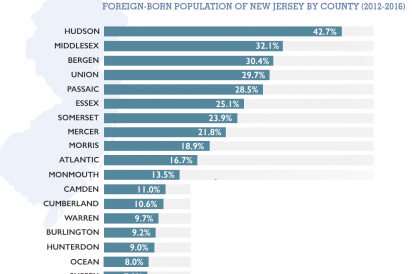

With one of the largest first-generation immigrant populations in the country, New Jersey experiences disproportionately the effects of national immigration policy. The US Census Bureau estimates that one in five New Jersey residents was born outside the United States. New Jersey’s net population growth relies on international migration to replace Jersey-born residents moving out of the state. The nonpartisan Pew Research Center estimates 500,000 unauthorized immigrants living in NJ—more than 5% of New Jersey’s population; more than 8% of New Jersey’s labor force.

The food industry has always employed a large share of undocumented workers. According to Pew, unauthorized immigrants account for an estimated one-in-four foreign-born US residents, and 11% of the country’s restaurant and bar workforce. That translates into almost 30,000 undocumented workers in New Jersey’s restaurant and bar industry, a sector that employs more than 250,000 people.

With its reliance on an immigrant workforce, the food industry inevitably feels the impact of major changes to immigration policy, which have a direct effect on both documented as well as undocumented employees. Anti-immigrant policies adopted by the Trump administration, especially its “zero tolerance” immigration enforcement directives, are taking a toll on New Jersey’s food community, at all levels. New Jersey restaurants are struggling to retain and recruit workers, and to protect themselves and their employees from indiscriminate immigration enforcement. Jersey farms face similar challenges

The Trump administration has reduced humanitarian refugee admissions, banned travel from specific Muslim-majority countries, attempted to end legal protections for immigrant “Dreamers” brought to this country as children, and changed the enforcement priorities of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency.

A 2017 Executive Order calls on ICE to aggressively detain and deport all undocumented individuals in the United States— an estimated 11 million people. The agency within the Department of Homeland Security that once focused on border security and deporting undocumented criminals is now detaining any undocumented individual, including well-established immigrants with no criminal record who have lived in this country for years. The human impact of “zero tolerance” immigration enforcement is evident: parents separated from their children, individuals deported to countries they have never known, and an atmosphere of fear in immigrant communities across the United States.

ICE arrests nationwide increased almost 30% last year, according to data released by the agency. In New Jersey, ICE arrested 3,189 people in fiscal year 2017, a 42% increase over 2016, and one of the highest increases in the country. Forty percent of the undocumented immigrants arrested by ICE in New Jersey last year had no prior criminal convictions, up from 25% in fiscal year 2016. ICE agents have sought to detain New Jersey residents in their homes, while taking their children to school, at work and in public settings like local courthouses.

ICE has also dramatically increased its use of surprise workplace inspections, targeting New Jersey business owners.

“When I post an ad for an entrylevel job—for dishwashers, for bussers, for maintenance work— I don’t post an ad for Mexicans, I post an ad for hard working people who can do the work. The people who show up willing to work are Latino immigrants.” —Marilyn Schlossbach

Inspection & Enforcement

One morning in April 2018, ICE agents arrived unannounced at a North Jersey bagel shop. The ICE inspectors served the shop owner with a notice of inspection and asked him to turn over I-9 forms for his employees. (Form I-9 confirms a worker’s identity and authorization to work in the United States.) The bagel shop, in business for more than a decade, employed about 10 people. While in the shop, the ICE agents began asking employees for their names and identification. For years, the owner had kept W-4 tax forms for each employee with copies of each individual’s identity documents, believing he was complying with the law. The owner turned over to the ICE agents all the documentation for his employees. Following questioning, one employee was arrested on the spot and charged with being undocumented. Because the shop owner had neglected to fill out any I-9 forms, including for himself, ICE brought civil immigration charges against the business, with potential fines totaling $42,000.

According to ICE spokesperson Khaalid H. Walls, “A notice of inspection alerts business owners that ICE is going to audit their hiring records to determine whether or not they are in compliance with the law. Employers are required to produce their company’s I-9s within three business days, after which ICE will conduct an inspection for compliance. If employers are not in compliance with the law, an I-9 inspection of their business will likely result in civil fines and could lay the groundwork for criminal prosecution, if they are knowingly violating the law.”

Marilou Halvorsen, president of the New Jersey Restaurant and Hospitality Association (NJRHA), points out that ICE audits on restaurants have noticeably increased under this administration, especially in New Jersey’s most diverse and populous counties, like Hudson, Bergen and Passaic. Local immigration experts report that, shortly after the Trump administration took office in 2017, the Newark field office of ICE, which covers the entire state of New Jersey, began targeting for inspection restaurants and food markets in some of New Jersey’s most diverse, immigrant enclaves in cities like Paterson and Newark. Two New Jersey convenience stores were among 100 7-Eleven locations nationwide that received an unannounced audit by ICE agents in January 2018.

ICE continues to issue I-9 inspection notices at a pace that far exceeds prior years, increasing worksite inspections by more than 400% in 2018, according to data released by the agency. Once a restaurant, market or farm receives notice of an I-9 inspection, the law gives the business owner three days to comply and respond with the appropriate documentation for their workers. The bagel shop owner had inadvertently waived his right to take three days to respond by turning over employee documentation immediately when the ICE agents arrived.

When serving I-9 inspection notices in person, ICE agents are making so-called “collateral arrests” of individuals they suspect are undocumented, such as the bagel shop employee. Individuals have the right to not respond to questions from ICE agents unless the agents can produce a search warrant for the specific individual signed by a judge. ICE agents do not have the authority to stop, question or arrest just anyone. In practice, however, people confronted by ICE agents asking questions often comply. Halvorsen of the NJRHA is concerned about how ICE inspections and raids are being handled. “When ICE agents go into a neighborhood restaurant looking for someone with a criminal record, they start asking questions of everybody, and it scares everyone,” says Halvorsen.

“ICE has become a little heavy-handed,” she told ROI-NJ earlier this year.

The sanctuary city movement throughout the state has not deterred immigration inspections or employer enforcement. After a July 2018 operation in Central Jersey, for example, in which ICE arrested 37 individuals for being in the United States unlawfully, the Newark field office asserted in its press release that “ICE will continue to execute its mission” in communities like “Middlesex County, which aspires to be a ‘sanctuary county’ by protecting criminal aliens.” New Jersey communities that have publicly op- posed current immigration enforcement priorities include Asbury Park, Camden, Hoboken, Jersey City, New Brunswick, Newark, Trenton and Union City.

Unannounced employer audits were rare before this administration’s immigration crackdown. Since employers were first required, in 1986, to verify employment eligibility by completing an I-9 form for every employee, so-called “I-9 inspections” have typically been triggered by tips that a particular business was intentionally hiring individuals without work authorization, or as the result of an investigation into criminal activity.

The administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy extends to employers who make errors filling out forms, even if all their employees are authorized to work. “Employers being audited typically would have the opportunity to correct any record-keeping mistakes and supply any missing paperwork,” says Raymond Lahoud, a prominent New Jersey immigration lawyer. “If mistakes were found in employee paperwork, government investigators would typically issue a warning, at most, and often show a small business owner how to correctly fill out the paperwork.”

Today, he says, the situation differs, and gone is any flexibility being demonstrated by ICE. “ICE is becoming more aggressive. ICE seems to be focusing on employer enforcement, which is easy and lucrative.” Civil fines range from $220 to $2,191 per paperwork violation. “ICE is going after the money,” Lahoud says. “Restaurants are a huge target right now.”

“In New Jersey, pizzerias, Chinese restaurants, Indian restaurants, Middle Eastern restaurants—those that have always been perceived as employing immigrant workers—are all being targeted for I-9 audits,” says Lahoud. So far, upscale restaurants have not been targeted, but Lahoud believes it’s just a matter of time. “Restaurant owners in relatively affluent New Jersey suburbs should also be preparing for inspections.”

Lahoud predicts ICE will also expand its inspection targets to include wholesale distributors in New Jersey’s food industry. According to Lahoud, the use of these tactics against the food industry looks to get worse before it gets better.

An ICE spokesperson declined to discuss specific immigration efforts in New Jersey, including what percentage of I-9 inspection notices have been served to NJ restaurants, and whether ICE is targeting specific communities or types of restaurants for immigration enforcement. “ICE’s worksite enforcement strategy focuses on the criminal prosecution of employers who knowingly hire illegal workers. ICE will also continue to use I-9 audits and civil fines to encourage compliance with the law. Any workers encountered during these investigations who are unauthorized to remain in the US are subject to administrative arrest and removal from the country,” said ICE spokesperson Khaalid H. Walls in an e-mailed response to questions.

Being Prepared

Halvorsen, of the New Jersey Restaurant and Hospitality Association, believes restaurant owners should give some thought to what they will do if they receive an inspection notice or visit from ICE agents. Many New Jersey restaurateurs and chefs who comply with employment regulations have never had to consider these questions.

Marilyn Schlossbach, executive chef and owner of three restaurants and a catering business in Asbury Park, says that if ICE were to show up, “I would give them what they ask for.” Similarly, Chef Bucco has never been the subject of an ICE visit. As part of a hospitality group with multiple restaurants and 700 employees, he relies on the group’s human resources department to handle employment paperwork properly. If ICE agents showed up at his restaurant, he says he would treat the visit the same way as any health or other inspection, starting by asking them to show appropriate identification. Beyond that, he admits to not knowing what his specific rights are in that situation. “[My team] trusts that I am looking out for their best interests,” Bucco emphasizes. “It is important for me to know how to protect my people.”

Family-owned restaurants in New Jersey’s immigrant communities face the greatest risk of indiscriminate immigration enforcement. Lahoud tells his restaurant clients to train their front of house staff on what to do if ICE inspectors show up. His recommendations include: interacting with ICE agents away from customers and employees; limiting ICE access to the restaurant by keeping them in the vestibule or outside; not allowing ICE agents to speak with employees; not turning over documents immediately; and, not surprisingly, contacting an immigration lawyer. While Lahoud emphasizes that employers should be proactive, he acknowledges that most restaurant owners are not—they typically talk to an immigration lawyer only after receiving an inspection notice or a visit from an immigration agent. (See sidebar, opposite)

“Everyone in the food industry knows someone who is undocumented,” says Lahoud. “People are really scared.”

“This is a huge melting pot industry. I’ve had the luxury of working with people from all over the world.” —Chef Anthony Bucco

Need for Reform; Need for Employees

“Zero tolerance” immigration enforcement is draining an already shallow labor pool for New Jersey restaurants due to its impact on all immigrant workers. Maria Nieves of the Hudson County Chamber of Commerce points out that current immigration policies make it very tough for business owners to find entry-level employees, especially as the labor market tightens. In July, New Jersey’s unemployment rate fell to 4.2%, its lowest rate in 11 years.

“To continue to be competitive, business owners don’t want any policies that disrupt immigration,” says Nieves. Her organization has advocated for immigration reform, “which could have avoided the situation we’re in now.”

The owner of a prominent Central Jersey hospitality group is feeling the impact of the restaurant workforce shortage. Heading into his busy fall catering season, numerous positions remain unfilled at his group’s South Asian restaurants—including restaurant managers, floor staff and dishwashers. In the past, he would fill key positions by recruiting experienced restaurant managers from India through the skilled immigrant work visa program. The Trump administration has made the work visa application process more difficult, denying more immigrant visas than ever, creating headaches for employers that rely on foreign workers to fill open positions. The owner, who declined to be quoted or identified by name, had no problem attracting talented Indian culinary professionals in the past. Today, the obstacles and uncertainty surrounding U.S. immigration policy are dissuading applicants. He sees a lot of uncertainty and concern in the restaurant industry, with the true impact of changes to immigration policy not being known for years to come.

Chef Bucco faces similar challenges. When he led the Stage Left kitchen in New Brunswick from 2003 to 2009, it was easy for him to find talent. “People would walk in the door looking for work.” At the Ryland Inn, he says, a Craigslist ad resulted in dozens of applicants. At Restaurant Latour, the lack of a local immigrant labor pool in Sussex County was a big source of stress in operating the restaurant, Bucco notes. Today, he says: “Forget it if you are trying to hire for restaurant positions.” There is no real workforce to draw from, Bucco points out. “Few people are applying to fill restaurant positions. You only get a handful of responses to an ad.” Bucco speculates that a high level of fear and suspicion may be contributing to a reluctance among some restaurant workers to change jobs. For fear of having to submit documents again, some workers, he says, may be “prisoner to their existing job.”

Seasonal businesses that rely on temporary visa programs to fill open jobs, like Jersey Shore restaurants, have been especially hard hit by immigration restrictions. “If you went to a restaurant down the Shore this summer and noticed open tables in the dining room but still had to wait 45 minutes to be seated,” says Halvorsen of the NJRHA, “it was probably because there were not enough workers in the back of the house for the restaurant to operate at full capacity.” Restaurants can’t serve customers, because fewer people are working behind the scenes.

Marilyn Schlossbach hires around 100 seasonal employees every summer in Asbury Park. Ninety percent of her employees are first- or second-generation immigrants from Asbury Park’s Latino and Haitian communities. She emphasizes that restaurant owners are looking for a workforce that is qualified, but they are not finding that workforce outside immigrant communities. “When I post an ad for an entry-level job—for dishwashers, for bussers, for maintenance work—I don’t post an ad for Mexicans, I post an ad for hard working people who can do the work,” says Schlossbach. “The people who show up willing to work are Latino immigrants.”

Ehren and Nadine Ryan, from Australia and Austria respectively, immigrated to the United States on investment visas, became permanent residents and have invested in New Jersey’s food economy by launching Millburn’s award-winning Common Lot, considered one of New Jersey’s top restaurants. “Restricting legal immigration right now is exactly what New Jersey restaurants do not need,” says Chef Ehren Ryan. Ryan sees a worldwide shortage of chefs, especially here in New Jersey. It’s hard for New Jersey kitchens to attract mid-level chefs when competing with restaurant opportunities in cities like New York and Philadelphia. While up and coming USborn chefs typically go overseas in their 20s to gain professional experience, it is becoming more difficult for foreign chefs to train here. Ryan knows of two former highly qualified Australian colleagues who wanted to train in the United States but were recently denied work visas. Both now work as sous chefs in Canada.

“Immigration policy needs to attract people into the industry from overseas,” says Ryan. He worries that there are not enough people pursuing restaurant work as a career in New Jersey, at all levels, from servers to kitchen hands. “The industry could collapse if not enough people are willing to go into it.” Ehren and Nadine have considered expanding their popular restaurant, which employs around 25 people, but they are hesitant. “My biggest concern is not about cash, customers or construction—it’s staffing,” says Ehren.

“Restricting legal immigration right now is exactly what New Jersey restaurants do not need.” —Chef Ehren Ryan, Common Lot

An Industry Inspired and Supported by Diversity

The importance of immigration to New Jersey’s best chefs and restaurants cannot be underestimated. “New Jersey has the most diverse culinary scene, thanks to its immigrant history,” notes the NJRHA’s Halvorsen.

Chef Anthony Bucco readily acknowledges that his own cooking has been influenced by first-generation immigrants in New Jersey, from a young Mexican dishwasher who introduced him to the best homemade tamales in New Brunswick, to a Peruvian beverage director at the Ryland Inn in rural Hunterdon County, to Martyna Krowicka, the Polish- born former Chef de Cuisine at Restaurant Latour at Crystal Springs Resort in Hamburg (“Her Own Beet,” Edible Jersey, Winter 2018). Bucco is now Executive Chef and Partner of Felina Restaurant in Ridgewood, where Chef Krowicka is Chef de Cuisine. “Look for a play on a pierogi on the Italian menu,” Bucco says. “Those who pay attention will see her Eastern European sensibility reflected in Felina’s Italian country cuisine.”

“This is a huge melting pot industry,” Chef Bucco emphasizes. “I’ve had the luxury of working with people from all over the world. I look for unique cultural backgrounds. I don’t want to lose that diversity in the kitchen.”

“As restaurateurs, we don’t want people to feel threatened,” says Jeanne Cretella, President of Landmark Hospitality and past chair of the NJHRA. “Immigration reform is really important for an industry like ours that relies on a diverse workforce.”

For Chef Ehren Ryan, an immigrant himself, “it’s vital to have chefs from different backgrounds who can share their knowledge of different flavors and ingredients.” In his kitchen, one cook is Filipina-American; another is Peruvian-American. They have added Southeast Asian and South American influences to the menu.

“Our industry needs a movement for comprehensive immigration reform,” says Marilyn Schlossbach. “It’s a critical time.” Schlossbach believes New Jersey chefs and restaurant owners, who, she says, have become more open-minded on immigration, need to speak up and get involved. “With reasonable immigration policies, we could meet our seasonal labor needs.” She points out that work visa programs are a drop in the bucket, however, compared to overall immigration policy. “Immigrants make whatever sacrifices are necessary to build a better life for their families.” Schlossbach knows immigrant workers who have almost died crossing the US border, who have missed seeing their kids grow up and who have been unable to attend the funerals of close family members because they are working here. “These are the things that break my heart, knowing that I don’t have to live 3,000 miles away from my children to support my family,” she says.

Reflecting on the impact of “zero tolerance” immigration enforcement, Chef Anthony Bucco starts to get animated. “A lot of good people are being screwed,” he says. “It’s hard to see people being abused. It’s very unfair. Immigrants have founded, protected and grown this country.”

Then he tells a story about his grandfather: “Growing up in Matawan, while my Italian grandfather was alive, I used to tease him about never eating green beans. He never ate green beans, in any form. When I started cooking professionally, I would tell him, ‘try my green beans, Pop Pop, they’re delicious.’ He wouldn’t try them. Finally, he told me why. He was the sixth of 11 children born to parents who had come to New Jersey from Italy in the 19-teens. From the age of 9 until he was about 15 years old, he had worked every summer as a field worker on a Monmouth County farm, near Holmdel. His job was picking green beans all day. And he was allowed to keep as pay a percentage of what he picked. So, he and his immigrant family ate a lot of green beans when he was a child. His hard work paid off. This country gave him an opportunity to stay and to succeed. He, together with all his brothers and cousins, served this country in World War II. He made a good life for himself and for my father. He never had to eat green beans again. To this day,” Bucco says with pride, “you will never find any green beans on my menus.”

“I can’t imagine what his life would have been like if, in addition to working to survive as a child, he had to worry about a government agent showing up at the farm to deport him, or to fear someone taking his mother away while he was at work.”