Building a Better Meat System

HARRIS BELIEVES THAT IF CONSUMERS SHOP THEIR VALUES, MEANINGFUL CHANGE CAN HAPPEN.

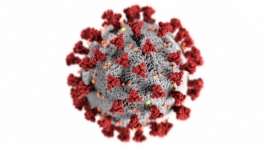

All it’s taken to expose the precarious state of our modern industrial meat supply is a tiny bit of infectious genetic material wrapped in a protein coat. The coronavirus pandemic has shone a not-so-friendly light on the inhumane ways both animals and people are treated in a system dominated by four major companies: Tyson, JBS, Cargill and National Beef. Over the past 40 years, as the meat packing industry has consolidated in the name of scale, efficiency and profits—and while consumers have been the beneficiaries of cheap meat— producers, rural communities, slaughterhouse workers and the environment have all paid a steep price.

As the virus rampaged through enormous packing plants in the Midwest, sickening thousands of mostly immigrant workers and, as of June, killing more than a hundred, the packers slowed production and claimed a meat shortage was imminent, sending meat prices soaring and panicked consumers to clean out grocery store meat cases. In the meantime, decreased packing house capacity meant farmers had nowhere to sell their animals and were forced to exterminate millions, mostly hogs and chickens, the disposal of which by burying or incineration has created serious groundwater and air pollution. In the modern industrial system, once animals reach their slaughter weight, there’s no alternative to mass euthanasia and disposal if the facilities aren’t available.

“What do you do with a million cattle and no slaughter capacity? You cannot keep feeding them,” says Mike Callicrate, a rancher in St. Francis, Kansas who owns a small slaughter plant, along with a processing plant and retail store in Colorado Springs. He’s also a fiercely outspoken advocate for small family farms.

“These companies are so unbelievably fragile. One little thing happens and they fall apart. It’s just a house of cards,” he adds. In the late 1960s, the U.S. was home to around 9,000 medium and small-scale slaughter plants scattered throughout the country. By 2018, that number had shrunk to about 800, with the vast majority of beef and pork processed in only about a dozen extremely large plants concentrated in the Midwest. Not only does this leave the meat supply vulnerable to disruption, but as small plants have disappeared, it’s become harder for livestock growers to opt out of the industrial system, and small rural economies have collapsed as competition has disappeared and dollars have been siphoned off by massive corporations.

Callicrate places many of the problems inherent in the commodity meat system at the foot of USDA for several reasons, but especially when it comes to truth in labeling, another issue depressing prospects for small producers. “We’ve got USDA out there acting like they’re the food police and making sure our food is safe and wholesome, and yet they are complicit in one of the biggest labeling frauds in our history, Product of USA,” he says. “We’ve got to realize that USDA does not represent the people’s interest anymore.”

Consumers may think they’re buying American beef when they read “Product of the USA” on the label, but meat can legally carry that terminology even if it’s imported from countries like Australia or Brazil, as long as it’s processed in a U.S. packing plant. The misleading product of the USA label goes hand in hand with the end of Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) for beef. When Congress allowed the industry to drop the country of origin from the label in 2015, the doors opened wide for consumer confusion, especially with grassfed beef.

“The USDA rule that allows multinational corporations to shop for grassfed beef in the cheapest markets in the world and then sell it to the most lucrative market in the world (the U.S.) and call it product of the USA is a major issue,” says Will Harris. He’s the fourth-generation owner of White Oak Pastures in Bluffton, Georgia. In the mid-90s, he began transitioning his commodity cattle operation to a pasture-based, multi- species model, and now is vertically integrated, with two slaughter plants and a robust sales and marketing department that moves product through several different sales channels, including retail, food service and direct-to-consumer.

In the years since COOL ended, Harris says he’s seen his business revenues drop almost 25 percent. “We’re selling the same amount of beef,” he says, “but our margins are dropping because we’re competing with cheaper meat from other countries.”

But there’s one pandemic-related glimmer of hope: When the Big Four slowed and shut down plants, small producers who had direct-to-consumer sales channels in place saw an onslaught of business. For both Callicrate and Harris, it was unexpected and somewhat overwhelming. “We’re just trying to figure out how we’re going to adapt,” says Callicrate.

Harris says his farm was inundated with orders from new customers, and that left some of their regulars in the lurch. “I was embarrassed that I allowed our regular customers to go without,” he says. His team is building a loyalty program to potentially alleviate that situation in the future, and he’s considering increasing capacity in the farm’s fulfillment center if business keeps up.

But will the sudden interest in local meat from small family farms last and create meaningful change in the industry?

Callicrate says it’s up to both the government and consumers. “Part of it depends on what the government does,” he says. “If we continue to allow these big meat packers to run chains at 400 head an hour and have workers standing shoulder to shoulder, paying them below living wage, and allow the continuation of these animal factories that are inhumane and polluting, and if we don’t protect the better local or regional model, nothing will change. It’ll go back to hiding behind the curtain again, as it has been for 30 years. Right now, consumers are learning about what’s actually happening. They’re seriously concerned.”

But he adds, “One of the worst, most deadly diseases in our country is aggressive price shopping consumerism because it wipes out your economy. Eventually it’s all gone. Your money is being siphoned off into the Walton family bank account, along with a handful of other multinational corporations. So that’s the really big dread, that people will not start considering more than price in their purchasing.”

Harris believes that if consumers shop their values, meaningful change can happen. “Right now, there aren’t very many people doing what we’re doing, maybe about 20 of us in the whole country. I don’t think any of us care about becoming hundred million dollar companies, but if there were a hundred companies doing what we’re doing, then we could build those regional food systems.”

So how does an aware and enlightened consumer help grow a sustainable and healthy food system? Harris offers some tips:

- Decide what values you want to support, whether it’s animal welfare, regenerative agriculture, healthy food, local farms or a combination.

- Find a farm or ranch that fits your values and don’t rely on package labels or certifications. In these days of social media, it’s increasingly easy to learn about how businesses run. Most family farms have websites and engage with interested potential customers on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest and others. Ask questions; get to know the people producing your food.

- Once you find a farm or two, buy their products and support them. “Consumers buying from us is the air we breathe,” says Harris.

Callicrate sums it up. “The consumer is the only way we get out of the ditch. They’ve got to support something better.”

“Though I am by no means a vegetarian, I dislike the thought that some animal has been made miserable in order to feed me. If I am going to eat meat, I want it to be from an animal that has lived a pleasant, uncrowded life outdoors, on bountiful pasture, with good water nearby and trees to shade.”

—Wendell Berry, The Pleasures of Eating

WHEN THE BIG FOUR SLOWED AND SHUT DOWN PLANTS, SMALL PRODUCERS WHO HAD DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER SALES CHANNELS IN PLACE SAW AN ONSLAUGHT OF BUSINESS.

DON’T BE FOOLED

According to current USDA regulations, meat brought in from other countries and processed here can be labeled “U.S.” with no transparency (or regulation) regarding its origin. Don’t be fooled by labels that say “U.S. Grassfed” or other claims.