The Evolution of Farm-to-Table

Behind many a stunning restaurant meal, there’s a farmer as well as a chef

There’s no doubt that the accolades poured on great chefs are well deserved. Many have earned it through years of training and learning how to handle ingredients in a way that makes diners swoon. But before the food makes its debut on your plate, there are farmers—probably many farmers—whose skills and dedication are just as important to the making of that stellar menu.

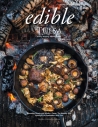

Sitting at the bar at the Farm and Fisherman in Cherry Hill talking to chef Todd Fuller, I hear a story forged through a love of heirlooms. I’m eating a bowl of chili. It is a cold, grey weekday and the restaurant has just opened for lunch. Chef Fuller describes the special beans in this bowl; they’ve been cultivated at his request by Barry Savoie and his wife Carol, owners of Savoie Organic Farm in Williamstown.

Already he is looking forward to putting up this year’s harvest, dried on the vine, for a winter’s worth of soups and stews. To hear him describe the quality of these beans and the pot liquor and the residual stock they produce is mesmerizing. He calls the beans “perfect,” and it’s true. The bowl of chili lived up to every hyperbolic sensory descriptor he used.

The restaurant is owned by chef Josh Lawler, whose resume includes a long stint at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, Dan Barber’s famous farm-kitchen atelier and food laboratory in New York’s Hudson Valley. Needless to say, Lawler knows quality local produce. This time of year, Lawler and Fuller chase their agriculture muse at the Savoie Organic table at the Collingswood Farmers’ Market. “I don’t go with a shopping list. I go to see what they have,” says Fuller. Back in the kitchen, creativity takes over and menu items—truly local, farm-sourced menu items—are born and served in the space that each ingredient’s growing season allows.

“On the menu, almost all the time, we have Jersey potato skins. And we use whatever potatoes Barry has: Small Marbles, German Butterballs, Kennebecs,” says Fuller. Regardless of variety, the process is the same: They roast the potatoes first, then scoop them out or just smash them a little if they are small. Just before serving, they’re thrown in the fryer with rosemary, thyme and parsley, as well as onions, jalapenos and Benton’s bacon. “Then we season them and hit ’em with Mornay, which is like your mac’n’cheese sauce, a roux-thickened bechamel, finished with some Monterey Jack and Vermont cheddar.” The dish is unlike any plate of potato skins you’ve had before, and it starts with these exceptional potatoes. They’re the kind of spuds that inspire accomplished chefs to get excited over what is essentially bar food.

Peerless potatoes aren’t the only crop that gets this kitchen’s creative juices flowing. “Barry grows these really great peppers called shishitos. Whenever he has those, we use them to garnish the steak. They go into a hot black cast-iron pan and we cook them quick and hard, then season with salt. They’re great because one in ten is a little hot so it’s like a surprise,” says Fuller.

To satisfy lovers of Italian cuisine, Fuller makes a caponata with Barry’s squash. “If you go to Italy and get a caponata, it focuses on the tomato and the sauce is stewed down so that it’s spreadable,” he says. But because the produce from Savoie is so beautiful, the Farm & Fisherman team takes a different approach. “We finesse the traditional sauce with tomatoes, raisins, some anchovies, Dutch cocoa powder and chile flakes to punch it up, and serve with grilled bread and burrata cheese we get from Lioni [Latticini] in North Jersey,” says Fuller.

As he’s describing these, I can imagine him standing at the market over a rustic box of each justdug thing he’s named, putting sense-memory and imagination to work.

For Barry and Carol Savoie, this symbiotic relationship means hearing what chefs like and want and dedicating space in the season’s planting for those crops. For instance, Lawler showed Barry a box of the pale yellow Great White heirloom tomatoes he’d picked up elsewhere in the farmers’ market. This year, Barry will have them on offer. But it goes the other way, too: Often the farmer finds a rare, one-of-a-kind heirloom and works to bring it to the chefs.

One such heirloom is a pepper called Katishtya. Similar to a New Mexico Anaheim, but short, only four to five inches long, the pepper ripens to a deep mahogany. Barry got the seeds from a customer named Felice at the market. He can’t remember her last name (“because I only see her a few times a year in August”) but he remembers the pepper acquisition vividly. An artist from the Puebla region of Mexico, Felice travels back and forth to her parents’ farm in the northern Rio Grande valley. She explained that her family had been saving seeds for this particular pepper for four or five hundred years.

In the fall of 2014, Barry says, Felice “showed up with this tiny container with a little label that says ‘Katishtya.’” Inside, there were a few little seeds. There were bits of dried pepper in the container as well, and Barry tasted some. “It was sweet, smoky, a little heat.” Barry planted the gift and, on the first round, had a seed failure. “I got down to like thirty seeds and put everything I had into making sure those grew. Now I’ve got about a thousand seeds. I’m really honored that her family trusted me with them and I’m really excited to give them to the chefs this year. They don’t even know I have them!”

In addition to the ephemeral summer offerings, Lawler and Fuller both lamented to Barry that no one is locally raising shelling beans for storage—chefs all over are ordering them from as far away as California. “This makes no sense,” says Fuller. “They are easy to grow and easy to store—just put them in a jar up on a shelf. We’ll make space for that.”

Seeing an opportunity, Barry brought the chefs some brown and white mottled Jacob’s Cattle beans that he had grown and threshed by hand. Their enthusiasm was so overwhelming that Barry worked with the duo to decide what other varieties would excite them. But there was a catch: Hand threshing was out of the question. It is so labor-intensive and time-consuming that it would make the beans prohibitively expensive.

By chance, during this planning process, Barry came upon an International Harvester model 82 tow-behind thresher at a farm sale in Pennsylvania. It came complete with its 1960s-era user’s manual and original coat of paint. This solved the threshing problem but ruled out varieties of pole beans, as the combine can’t harvest around their armature.

So Barry and the chefs set their sights on the rainbow of bushgrown beans. They now grow rich, maroon Vermont Cranberry beans, Mexican Black Turtle beans perfect for soup, creamy Quincy Pintos and Kenearly Yellow Eyes, all plump and ready to become an exceptional bowl of chili—the kind that can only be created when a farmer and a chef work together.

Farm & Fisherman Tavern

1442 Marlton Pike E., Cherry Hill

856.356.2282

fandftavern.com

Savoie Organic Farm

990 E. Malaga Rd, Williamstown

856.629.9020

savoieorganicfarm.comfarm