Clams 101: A How-To Guide

A clam is a bivalve invertebrate that lives on the floor of the ocean and covers itself with sand or mud. Hard shell clams (a.k.a. quahogs), soft shell clams (a.k.a. steamers, the ones that look like tiny, little anatomically correct . . . clams! What did you think I was going to say?), razor clams and geoducks (pronounced “gooey-ducks,” which look like big versions of the soft shell clams) are eaten all over the world and prized for their culinary versatility and briny flavor. They are inexpensive and easy to catch. Be sure to abide by all regulations concerning licenses, permits and catch limits, as fines can be steep.

How to Buy Clams: Lips Sealed Tight

A clam is alive when its two shells are shut tight together, protecting the little animal inside. You may see the lips pursed slightly if a clam is bored or tired, but tapping it against the counter or squeezing it between your fingers will remind the clam that it’s about to be dinner, and Survival 101 should kick in. If the clam doesn’t snap shut, throw it away. It’s dead. A decaying clam provides a fast trip to the infirmary.

Clams are best the day they are harvested. If you need to store them for a day or two, place them in a colander set inside another bowl. Wet a paper towel, wring it out, and place the towel on top of the clams. Put everything in the fridge. No water, no plastic. (Clams may be stored this way for up to five days, but just barely. Don’t eat five-day-old clams raw. You’ll be disappointed. Use them for baked clams or chowder.)

How to Catch a Clam

Catching clams requires just your feet and a bucket. You don’t even have to know how to swim, because clams are easiest to catch at low tide. Need a second opinion as to the ease of the pursuit? My grandmother, mother to five girls, told her teenage daughters, “Whatever you do, don’t bring home any clamdiggers.” Lucky for me, my mother ignored that advice to marry my clamdigger dad.

Nothing is better than low tide lining up with 5pm on a sunny day on the bay. At the edge of the water you’ll see the tidal salt marsh, the wide expanse of green grass, black mud and water running with the wind and tide, and the shore birds picking around, looking for a snack. I love how it smells: an intoxicating combination of sea and salt and oceanic decay that whispers, “Emily, you are home.” Occasionally, I’ll smell something reminiscent (usually food lost in the fridge or odors blowing around New York City) and say, “Mmmmm . . . smells like low tide.” I mean it as a compliment.

Walk out through the water to the exposed sand bar. That’s where the clams are. Find a spot and start stepping around, feeling in the mud, about 4 or 5 inches below the surface, for something that feels like a buried golf ball or baseball. This technique is called “treading.” (Yes, someone came up with a word for “walking around in the mud.”) When you feel something hard under your toes, reach down with your hand and pull it out. If it’s a clam, rinse it off and put it in your bucket. That’s one. You’ll need about 47 more littlenecks to feed four people.

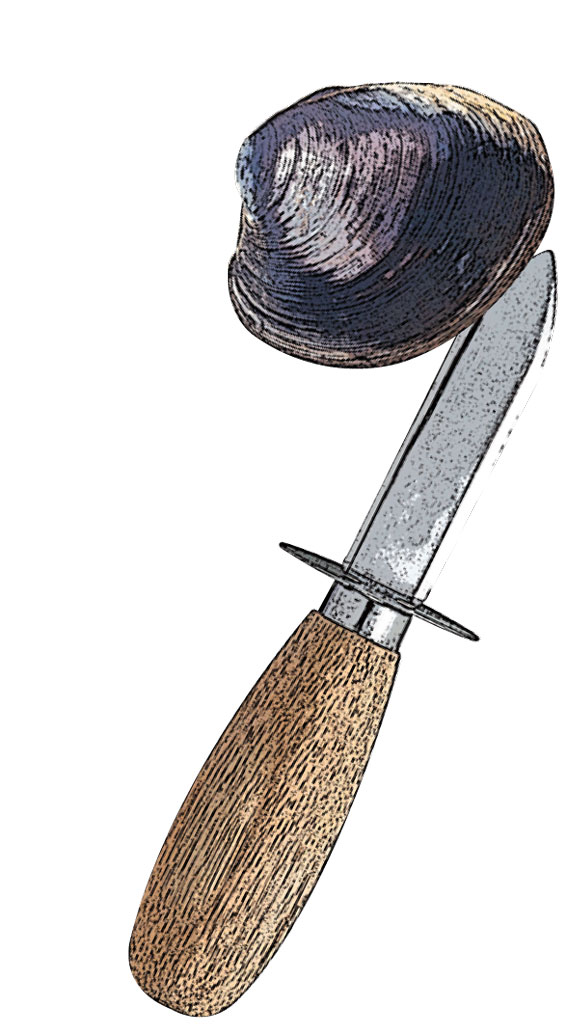

Kill It: How to Open That Which Doesn’t Want to Be Opened

Clams don’t want to be pried open. If you are eating the clams raw, you’ll need a clam knife. Essentially a butter knife with a thinner edge on the “blade” side, the clam knife’s design allows for wedging between the clam shells without cutting off your fingers.

Hold the clam in your non-dominant hand with the hinge nestled in the flesh between your thumb and forefinger. Hold the knife handle in your dominant hand and line the tapered side of the blade up between the two shells, in the lips. Use the four fingers of the hand holding the clam to squeeze the blade into the clam. Once the back of the knife is flush with the lips, use your dominant hand to twist the knife and pop open the shells. Run the knife along the inside of the top shell and cut through the muscle holding the clam in place; remove the top shell. Run the knife under the clam and cut the mirroring muscle again. Discard one of the shells. Voila! Clam on a half shell.

Alternately, place the clams in the freezer for a few hours. This will kill them. When you take them out of the freezer, let them sit on the counter for 20 minutes or so, and they’ll open on their own.

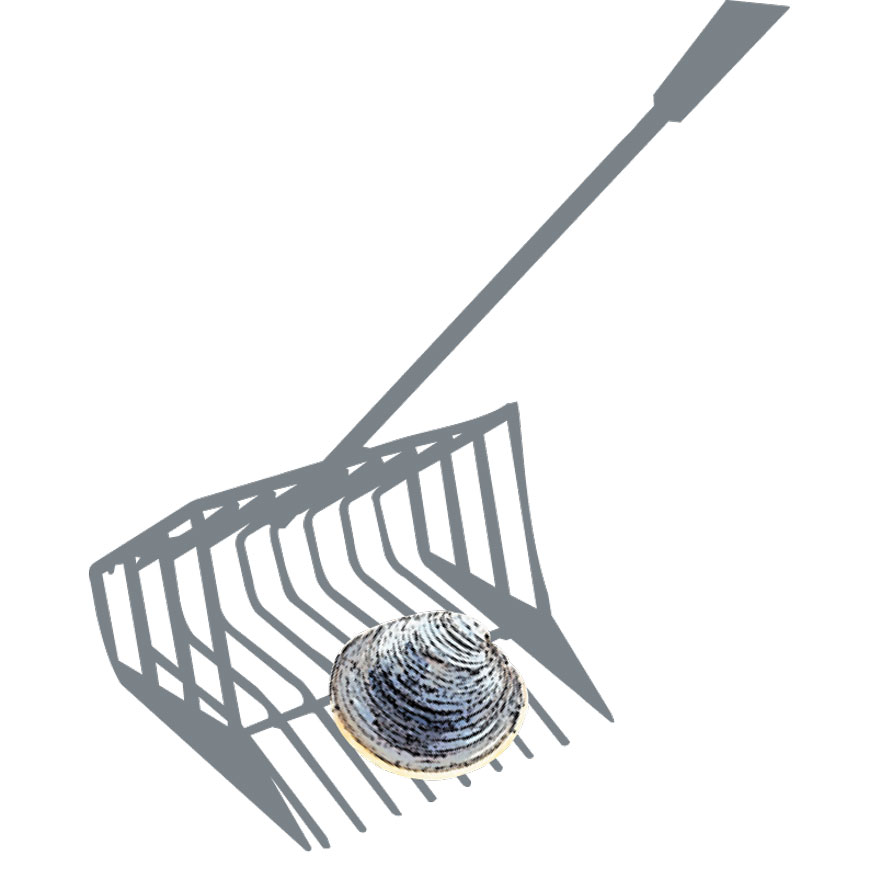

Optional Tools

If you want to get slightly more high tech, invest in a hand-powered clam rake (about $40). If you don’t want to look like you just bought a brand-new clam rake, search for them in the corners of sheds and basements at estate and garage sales.

The advantage of using a rake is that you can wear boots, thus protecting your feet from broken shells, discarded bottles, aggressive crabs and passive horseshoe crabs. Treading can do a number on a pedicure.

Another handy tool is a cull rack. Generally you use two. It’s like panning for gold. One cull rack shakes out the littlest clams (read: illegal but delicious, or so I hear), which you throw back. Through the other, only the littlenecks fall, leaving the cherrystones and the chowders behind, which can easily be sorted by hand, if you aren’t selling them commercially. And so on until you have baskets of clams sorted neatly by size.

For me, it’s bare feet and a bucket, low tide and a sunset, showing the world I don’t want to do anything else.

Cleaning Clams: Sandy Clams? Forget the Myths—Clams Are Inherently Clean

Every time I hear someone say “clams” and “sandy” in the same sentence, my skin crawls. Even award-winning food blogs perpetuate long-held misconceptions. Allow me to set the record straight:

Clams are not inherently sandy.

Did you hear that? “But I’ve had sandy clams,” you say. Yeah, me too. Allow me to explain:

A clam lives its life buried beneath a few inches of sand or mud. To eat and breathe, the clam siphons water through its entire body, keeping that which it needs (algae and oxygen) and expelling that which it does not (everything else). Clams only siphon water, not the surrounding mud or sand.

When a human comes along, three fates are possible:

- The clam senses the predator, closes up shop and goes unnoticed.

- The clam is pulled from its lair by a human. While this is happening, the clam is still trying to close up shop. But the smart, hungry human wins, and the clam ends up in chowder or on the grill.

- The clam is caught by a clam dredge, a powerful tool drawn by a boat across the ocean bottom. To operate this system, a high-pressure water hose sprays the bed of clams ahead of the clam rake to break up the bottom and loosen up the clams. The water pressure is sometimes so powerful that it blows sand back into the clams. Hence, sandy clams.

A tell-tale sign that a dredge was used to capture your dinner are chips along the lips of the clam. The force of water banging your clam and all his neighbors into each other has the effect of a hurricane on a low-lying area. Not pretty, and the clam shells come out damaged.

Nothing is inherently wrong or unsustainable about responsible dredging, but dredged clams will almost certainly have the sandin- your-spaghetti situation.

So what’s a cook to do? Ideally, catch your own clams. Or, buy clams directly from a clamdigger who can say, “Yup I dredge ‘em,” or “Nope, I use a rake.”

Never—under any circumstance—set clams in a bowl of fresh water to flush themselves clean. This kills the clam (which is fine if that’s your end goal), but the clam then relaxes, opens and releases all its delicious clam juice into the bowl of water, which I’m guessing you’re about to dump. At best, you’ve got brackish clams and you’ve diluted the essential clamminess to nonexistent.

If some time to flush is what you want, bring home a pail of water from the bay and let the clams hang out in that in the shade for a few hours so they can expel whatever is inside them.

What about a sprinkling of cornmeal or black pepper on the surface of the flushing water? I’ve heard this method framed as a way to encourage clams to eat/siphon/expel/whatever.

Here’s the truth: When you eat a clam, you eat the whole animal— all the soft tissue. The good parts and the parts you don’t want to think or talk about because those parts gross you out.

I guess the theory is the clams will ingest the cornmeal and expel whatever they’ve got half-digested, allowing you a certain smug thought: “I’d rather eat raw cornmeal than clam poop.” But consider this: A clam’s diet consists of algae (a plant), and so, while carnivores such as shrimp can have some of their ever-so-slightly-more-pungent digestive tract removed, clams are so G-rated in the diet department that a little partially-digested algae is kind of . . . delicious.

Which is why you are reading this story in the first place.