Pinelands Amaro Herbal Liqueur

If you’ve been following my Slow Drinks column this past year, you know that I frequently turn to the New Jersey Pine Barrens for cocktail ingredients and inspiration. I go in July to pick blueberries and huckleberries, in November to harvest cranberries.

But my favorite trip is in March, when I go not to find a specific fruit, but rather for the evergreen trees themselves to make a Pinelands-inspired amaro.

Before outlining how to make your own amaro, I feel it is my duty to demystify this class of spirits. Many people, if not most, don’t actually know what amaro is. Amaro (plural: amari) is the Italian word for “bitter” and typically refers to a bittersweet, herbal liqueur made from the distillation and/ or maceration of botanical ingredients in a neutral spirit that is then sweetened and often barrel-aged. It is typically consumed before a meal as an aperitif, or after a meal as a digestif. While Italian amari are the most common on the market, the tradition is popular across much of Western and central Europe and can actually be dated to Greco-Roman times.

In March, nothing is growing in the gardens or on the farms, so off to the coniferous forests of the Pine Barrens we go.

Monks, pharmacists and folk medicine practitioners would go on foraging journeys to the country, forest and garden to collect herbs, nuts, flowers, barks, fruits and seeds with purported medicinal and restorative effects. They would place these ingredients in an alcoholic medium to extract the beneficial properties. The subsequent sweetening of the solution would help the medicine go down, so to speak. In the 1800s, amaro’s reputation as a purely medicinal tonic changed, and it became embedded in the fabric of European (and eventually global) drinking culture. Amaro consumption wasn’t the only thing that changed. The global trade route introduced a whole new set of ingredients from far away places such as Asia, Africa and the Americas, and as a result, the days of the hyper-local, terroir-driven amaro are largely long gone.

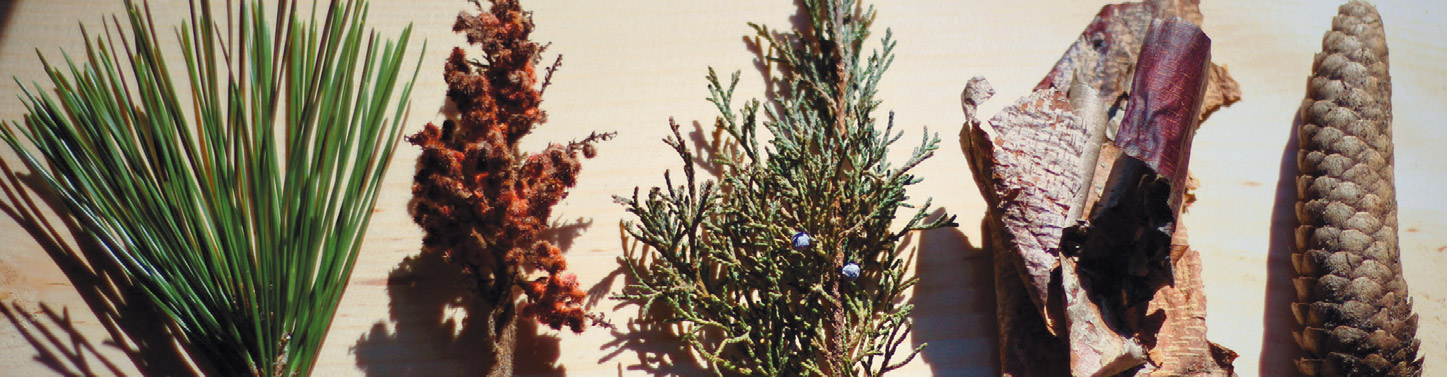

I found myself lamenting over this fact one day with our chef at the Farm and Fisherman, when we decided to challenge ourselves. Why couldn’t we make an amaro using ingredients only from New Jersey? We resolved to make one amaro each season over the course of the next year, right before the solstice or equinox, when the season is at its peak. Typically we search for ingredients by raiding our gardens, foraging and sourcing from farmers who supply fresh produce to the restaurant. But in March, nothing is growing in the gardens or on the farms, so off to the coniferous forests of the Pine Barrens we go. Pine cones and needles, cedar and birch bark, wintergreen leaves, juniper berries and staghorn sumac, all collected on one day’s walk through the woods. Little did I know it would be my favorite drink of the year.