Orley C. Ashenfelter

Orley Ashenfelter recently ended his active teaching career at Princeton University aft er more than 50 years in the classroom. An economics professor in the university’s famed Industrial Relations Section, his areas of specialty included labor economics, econometrics, and law and economics. Since he began teaching as a PhD student in 1968, the oft -awarded Ashenfelter has influenced and inspired many, including two eventual Nobel Prize winners.

What does this have to do with wine?

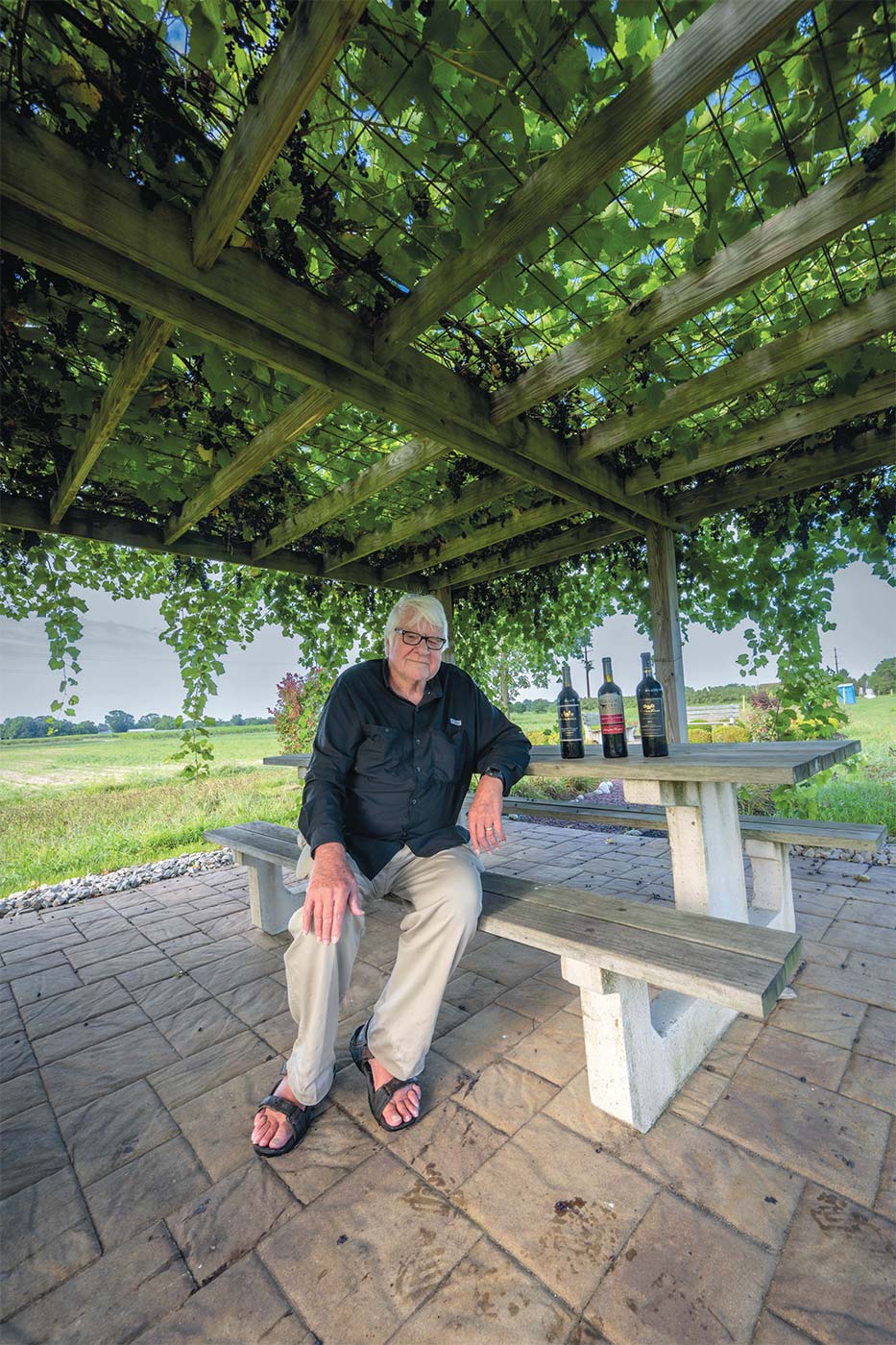

Over the decades, Ashenfelter has also possessed a parallel passion for wine. An interest in the economics of wine (originally developed with the intent of applying an economic model to finding the best-quality wines on a professor’s salary) eventually led to his co-founding the American Association of Wine Economists (AAWE) in 2006 and starting his own vineyard in Buena in 2015.

We met one hot summer afternoon at the vineyard and talked over lunch, a couple of bottles of wine (one made from his grapes), and during a few spins around his and adjacent farms in his John Deere Gator.

EDIBLE JERSEY: Thanks for inviting me to your vineyard and making the trek here yourself from your home in Princeton. Congratulations, too. You stopped teaching at the end of 2023. How does it feel?

ORLEY ASHENFELTER: Actually, I’m very happy with it. It gives me a lot of chances to get around. I can come down here; I can do whatever I want. It gives me a lot more flexibility.

EJ: How did you come to plant a vineyard here, an hour from where you live in Princeton?

OA: I was introduced to the area through my relationship with Larry Coia [owner of Coia Vineyards, co-owner of Bellview Winery in Buena], who I met in 2011. (See “Italian Renaissance,” Edible Jersey Fall 2023 issue). I started looking to purchase land almost immediately after we held the AAWE annual meeting in Princeton in 2012, purchased it in 2015, and planted my first block in spring of 2016.

Larry knew I had this wine interest and invited me to talk at a meeting of the Outer Coastal Plain Vineyard Association. Larry has been fixated on the idea that you shouldn’t be bringing in cheap grapes from elsewhere and making wine here. The idea is that this should be a local thing, and I agree.

At the event, I talked about wine economics along with AAWE Executive Director Karl Storchmann from New York University. During the event lunch, everyone brought wine, a lot of it barrel samples, many from the 2010 vintage, which was a fantastically good vintage throughout the state. If you couldn’t make good wine in 2010 with New Jersey grapes there was something really wrong with you. [laughter]

Karl and I tasted these wines and we were just amazed. It never even occurred to me. [At the time,] Until 2011, I didn’t actually know anybody was making quality wine in New Jersey.

.

WHEN THE GRAPES IN THE WINERY ARE FROM A SPECIFIC AND KNOWN VINEYARD SITE, THE WEATHER THAT PRODUCES THOSE GRAPES IS BASICALLY WHAT MAKES THE QUALITY OF THE WINE.

EJ: Your next move, based on this revelation, helped make a name for New Jersey wine and led to the Judgment of Princeton, an event similar in structure to the 1976 “Judgement of Paris, where California wines beat out many top French examples in judged tasting events with only French judges and the results led to a growing interest in California wine.

OA: Yes. The AAWE has a meeting every year in some wine region around the world. This year it is Lausanne, Switzerland. The AAWE was looking for a place to meet in 2012 so I said to the committee, “What the hell, why don’t we meet at Princeton?”

Everybody said, “How would you ever get any wine?” “No problem,” I said. “We got plenty of wine here. Are you kidding?” That’s how we actually ended up doing that.

EJ: I didn’t know this. So, it was the AAWE that helped create the opportunity for the Judgment of Princeton, which arguably was the first big publicity event for New Jersey wine in the modern era.

OA: That was how it happened. It was just an accident. Karl and I had attended a comparative tasting hosted by Lou Caracciolo at his Amalthea Winery [in Atco] in spring of 2011. George Taber, the only media representative at the famous Judgment of Paris in 1976, was also there. I had co-authored an article in 1999 with Richard Quandt for Chance magazine that was a statistical analysis of the Judgment of Paris results, so was no stranger to the concept.

We collected New Jersey wines and did a pre-event tasting in my house and yard to determine the final representative wines from here. The whole thing was really in the spirit of that original event, with some minor format changes, and it was all done at the university. … From it all, I got to know Larry pretty well and I started looking around to buy some land. His vineyard abuts mine.

EJ: The wines selected from New Jersey compared really well with the French wines from Bordeaux. Why, do you think?

OA: Similar weather and similar soil, for starters.

EJ: You have a particular specific interest in Bordeaux, having received an honorary degree from the University of Bordeaux just last year. How was that?

OA: It was pretty amazing! I had developed an example of regression analysis predicting wine prices with the vintage’s weather. It was credible and the product was interesting. It came to be known as the “Bordeaux Equation” and it really created a sub-field of economics. I imagine I was honored in part because the city and university liked having their own equation! We also did a big victory lap around France and visited other areas, like Chinon in the Loire Valley.

EJ: You got the wine bug, but most people don’t take it as far as you have. You also have taken your Bordelaise interest to this next level, too.

OA: I like a lot of other grapes, but I planted specific grapes here because of the location. When I looked at the climate here, it was just painfully obvious to me. It was very, very similar to Bordeaux. The soil, sandy loam, also is similar.

EJ: I know the theory where, [if] you flip New Jersey over, it’s similar topographically to Bordeaux, with significant water on two sides [in the case of New Jersey, the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware River].

OA: And Bordeaux doesn’t have hillsides or anything; it’s relatively flat. This [land] is a place that’s great for the Bordeaux red grapes that I grow—Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Petit Verdot. They also get the highest prices. I wasn’t really trying to make money or anything. I really did it more to try to maximize the value of the vineyard. I was kind of thinking, “You know, this is a pretty special place.” Larry has the same idea. And this whole area—when you look around here, I mean, look at this. This is like an agricultural miracle.

EJ: Not just your 12 acres of vines but the general area.

OA: First of all, there are a lot of good, smart farmers here. New Jersey is just unassailably among the very best in that regard in the whole country.

EJ: Do you think more people should be doing what you’re doing? The state has done a great job preserving farmland, but some say what is needed now are more farmers.

OA: If someone is interested, I’ll talk to them. It’s not really an easy way to make a lot of money, but it is a pretty satisfying way. It’s a nice way to preserve the agricultural part of New Jersey, but you still have to make a living off of the farming itself. It’s hard work. But on the other hand, compared to top wine regions, farmland is relatively cheap here.

EJ: What tip would you give to a New Jersey wine consumer? And is it different than the tip you would give to a New Jersey wine consumer as an economist?

OA: I would give them the same tip as an economist or anybody else. There’s a relatively small number of wineries in New Jersey that make high-quality wine, not unlike most other regions. You want to find out which ones they are and then get a connection to them. You’re not going to find these wines in the grocery store. Find out when a good vintage has happened, especially with red wines.

For white wines, it doesn’t really matter as much. I think white wines are a good example where, especially in South Jersey, vintages that aren’t so great for red wines are actually often very good for white wines. So white wines, I wouldn’t worry about the vintage year as much.

Red wines, you want to stock up on really good red wines from the best vintages. Don’t buy to just consume; buy for storage. If you’re going drink a case of wine all year, a really good wine, it’s worth it.

THIS [LAND] IS A PLACE THAT’S GREAT FOR THE BORDEAUX RED GRAPES THAT I GROW: CABERNET SAUVIGNON, CABERNET FRANC, AND PETIT VERDOT.

EJ: How does someone determine a good vintage year? As a consumer yourself, this is really what you based your original study on.

OA: Yes, I liked wine and started looking at this economically so I could figure out which wines to buy. What would determine that?

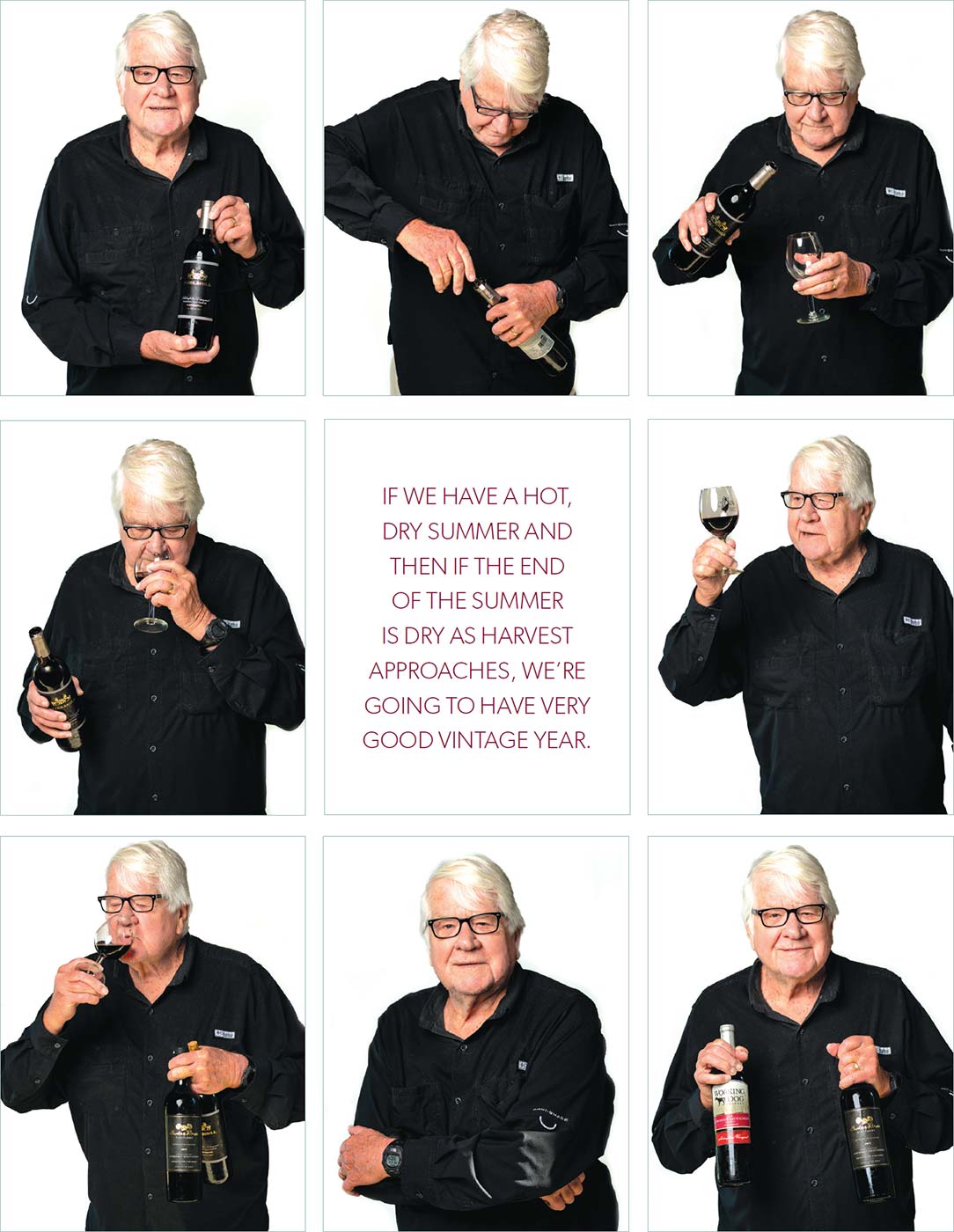

It’s kind of common sense, really. The idea was just a way to quantify what any farmer knows, which is, the weather in any given year. If we have a hot, dry summer and then if the end of the summer is dry as harvest approaches, we’re going to have very good vintage year. That’s just a way to quantify that. When the grapes in the winery are from a specific and known vineyard site, the weather that produces those grapes is basically what makes the quality of the wine. This is true right here in New Jersey, too.

EJ: Who buys your grapes?

OA: Unionville, Sharrott, most recently Saddlehill, the new winery in Voorhees. Of course, Hawk Haven and Cedar Rose, who both make single-vineyard wines from my grapes that carry the Ashenfelter name on their labels. We’re drinking the Cedar Rose Ashenfelter Vineyards Cabernet right now. It’s truly local to where we are sitting. I think it’s a helluva bargain! Vinetech, affiliated with Cedar Rose, planted my vineyard and maintains it. I was one of their first clients and they do a fantastic job. I like having my grapes at the different wineries instead of just one because I like to see what different winemakers are doing with them.