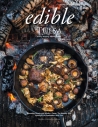

Mexican Rhubarb Mule

The arrival of May brings me great joy. After winter’s long hibernation, people and plants begin to reemerge and come back to life. One of the first true signs of warmer weather is the appearance of rhubarb stalks, with their huge elephant ear leaves.

My first encounter with a rhubarb patch was just three years ago. I was working on Plowshare Farms in Bucks County, PA. We had to take the tractor up the road for repairs. The mechanic, who worked out of a barn, was the son of a large farming family. The father once farmed a huge swath of land, but had since gone into semi-retirement. These days, the only crop he sells on a roadside stand is rhubarb, which he grows in a giant patch next to the repair shed.

I found the whole tractor mechanic /rhubarb operation fascinating. The family patriarch relinquishing all farming activities with the exception of one somewhat odd vegetable. Was it his favorite crop? Or a best-seller?

I continued to talk to locals about rhubarb, and I continued to hear personal, vivid memories. Picking rhubarb from grandma’s garden first thing every spring to make pie, sauce, jam, pandowdy or pudding. Siblings sitting in the kitchen, dipping raw rhubarb into sugar to cut the acidity. Kids having sword fights with the stalks.

Perhaps the reason for so many dynamic rhubarb memories is that rhubarb is the first thing to ripen in the garden in spring. But I also think it’s a generational memory, passed down through families here in the Delaware Valley, home to the oldest rhubarb traditions in the country.

“I continued to talk to

locals about rhubarb,

and I continued to hear

personal, vivid

memories.”

—Danny Child

The first rhubarb successfully grown in the US was by John Bartram in Philadelphia in the 1730s. Bartram was a Quaker farmer and botanist who had an interest in medicinal plants. He was sent rhubarb seeds from an English colleague who noted that the Chinese had been using the plant as a medicine for thousands of years. These same pharmaceutical applications caused Marco Polo to bring it back to Venice with him after his journeys through China, thus beginning a European market for medicinal rhubarb application.

To help the medicine go down, so to speak, Italians infused it in alcohol with other medicinal herbs, sugar and spices to make what we now call an amaro, a current obsession of craft bartenders around the world. Amari are bittersweet, herbal liqueurs first made by pharmacists and monks for their purported health benefits. Rhubarb- based amari became so common that they now have their own subcategory, rabarbaro.

Behind the bar, we’ve borrowed a page from the Italian playbook. Last year, we made a 100% Jersey-sourced rabarbaro with other spring botanics including wild violet, honeysuckle, strawberry and pine tips. We’ve also made rhubarb bitters, rhubarb ginger beer and a rhubarb-hibiscus syrup. These all come together with tequila in a drink I call the Mexican Rhubarb Mule. My wife, Katie, and I enjoy this drink so much, we served it at our wedding last year on May 5. The drink is perfectly refreshing for a warm night in May, but it also shows the versatility of rhubarb, and how it can be incorporated in so many ways in liquid form. Follow the recipe exactly, or use it as a touchstone to create your own rhubarb classic.