The Jersey Girl Who Transformed American Cuisine

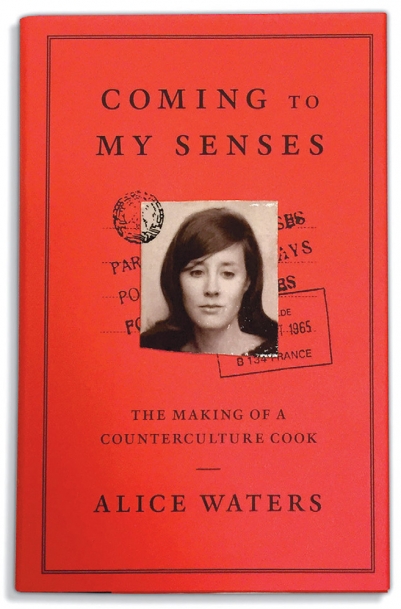

Alice Waters traces her journey in Coming to My Senses

One tends to think France-by-way-of-California when considering Alice Waters and her prix-fixe Berkeley temple, Chez Panisse. Yet the mother of American farm-to-table cooking spent her grade school years in Chatham. In her memoir; Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook [Clarkson Potter; 2017, with Cristina Mueller and Bob Carrau], Waters traces the unconventional path to her now-legendary restaurant’s 1971 opening. Spoiler alert: It begins in the Garden State.

This may surprise those unfamiliar with our bounty. To be fair; Waters half-jokingly writes of the slim sophistication found in a childhood New Jersey “cuisine,” where flourishes like wine pairings were unknown—the quotation marks are hers. Still, there were culinary breadcrumbs that pointed toward her trailblazing future.

As in the rest of post-War America, mid-century cooking here leaned on the grocery’s middle aisles. “Americans had never had deep roots in gastronomy or agriculture; we didn’t really eat for the pleasure of eating and we didn’t really grow food for flavor So when big companies came in with their time-saving cooking gadgets and short-cuts, we fell for them,” Waters writes. Her table was no exception, packaged hot dogs and Wishbone on iceberg in heavy rotation.

But there were also peach-coconut cakes adorned with summer-ripe fruit. There was garlic-perfumed chili con carne at her best friend’s house. Most influentially there was the sense of enchantment Waters discovered in her family’s Roosevelt-inspired victory garden.

“Some of the fundamental taste memories of my life are from the corn and tomatoes from that garden,” she writes. “There were tall lacy asparagus plants, tangles of red New Jersey beefsteak tomatoes, bell peppers, rhubarb, big patches of strawberries, and apple trees in the very back.” Her mother even entered four-year-old Waters into the Chatham community pool’s neighborhood costume contest as “Queen of the Garden.” Bedecked in a strawberry crown and a lettuce bodice, she won first place. Though the family eventually moved to Michigan City and then Los Angeles, these memories laid a foundation.

Befitting a college education at Vietnam-era Berkeley opposition to fast-food culture came to define Waters’ career. Yet that wasn’t her initial focus. A sensualist, she wanted to open a restaurant steeped in a Francophile obsession that blossomed during her college travels. Chez Panisse was a love letter to the buckwheat crepes, oozy cheeses and green salads that enchanted her. “I had been awakened to taste there, and I wanted everybody to be awakened the way that I had been.”

This would evolve in time, Waters’ terroir-driven mission becoming as reflective of American ingredients as of French technique. This earned her the first James Beard Foundation Best Chef in America Award given to a woman, in 1992. Later; in 2014, she would be given the National Humanities Medal for her Edible Schoolyard project. “The fast-food culture deprives children of seeing the beauty around them. They’re not experiencing it, not touching it, not smelling it, not living it through their senses.” Lucky for us, Waters had her own sensory awakening in that Chatham, NJ garden.