Community Garden Cultivates Organic Produce for Bridgeton’s Farmworkers

Growing Food Justice

A community garden deep in south Jersey’s agricultural region—and created to provide organic growing space for farmworkers—might sound counterintuitive. It’s hard to imagine that farmworkers don’t head home with the occasional box of fresh veggies—they planted, tended and picked them, after all. But the literal fruits of workers’ labor aren’t often theirs to enjoy, and low wages make it challenging for many farmworkers to keep themselves and their families fed. The Bridgeton Organic Community Garden, founded in 2012, is a key part of a strategy by one grassroots organization to ensure that the region’s farmworkers have affordable access to fresh produce for themselves and their families.

The garden announces itself to its downtown neighborhood with a bright orange picket fence. When I visited, organizer and food justice coordinator Kathia Ramirez and a dedicated garden member named Migdalia were painting a new sign featuring a man and a woman in farming gear, with festive vegetables and two hands cupping a bit of soil with a vibrant green seedling growing out of it.

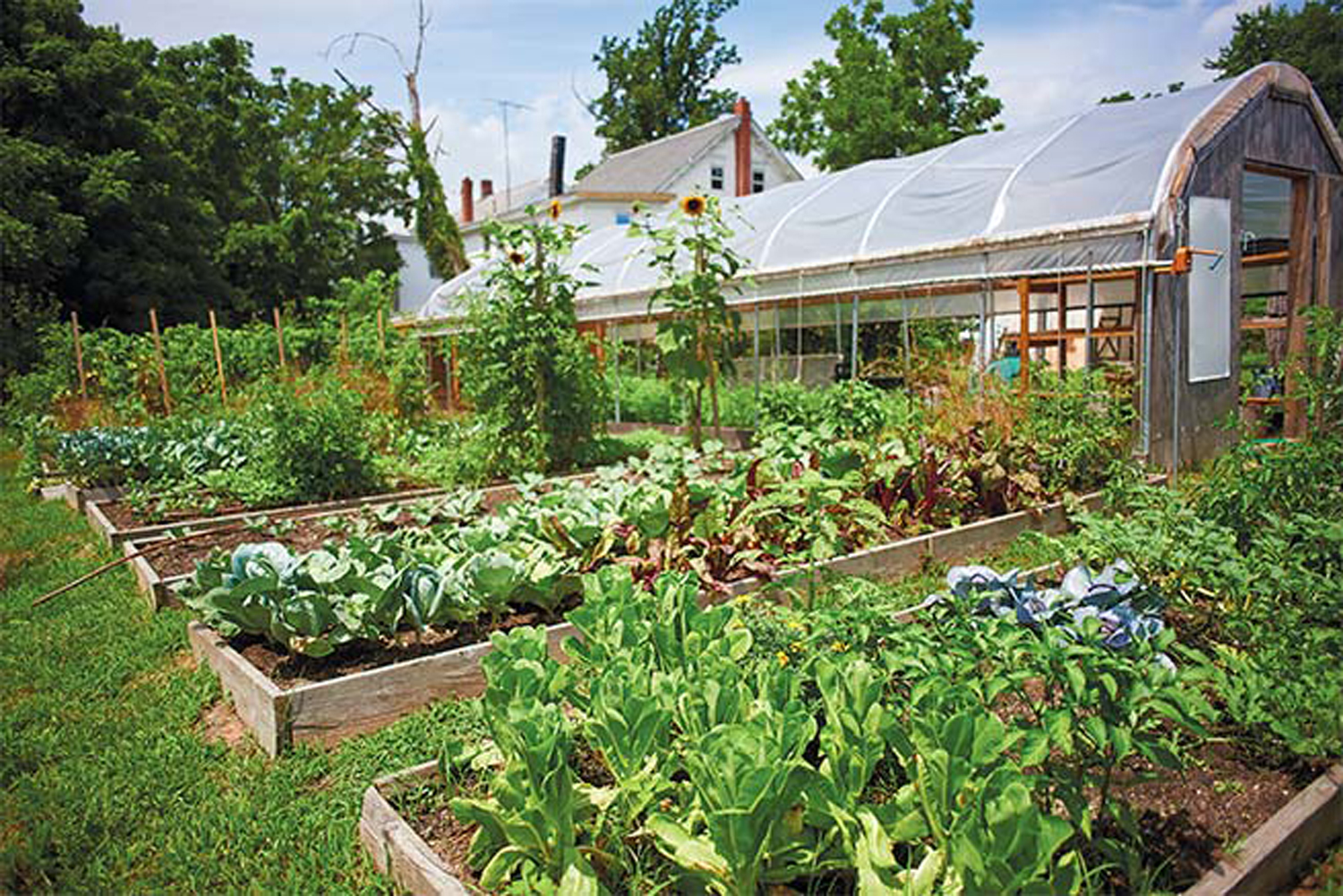

That two-hands logo represents El Comité de Apoyo a Los Trabajadores Agrícolas (the Farmworker Support Committee, or CATA), which started the Bridgeton garden in 2012. This project is part of CATA’s food justice programming. Thanks to the efforts of organizers and neighbors, a trash-strewn vacant lot was transformed into a community garden with raised beds, a storage shed and a small greenhouse.

“People were interested in getting involved and having a space” to grow organically, says Ramirez, who has been working with the garden for the past year. In line with the group’s mission, organic growing practices are a requirement at the garden, giving farmworkers a chemical-free zone to care for plants.

“This space was an initiative to [create] access to healthy food, free of charge,” says Ramirez. “Now we have produce available for people who get involved in the community garden.” Community members who help out can harvest for free, and garden organizers sell produce to others at a low price. Revenue is plowed back into the garden’s budget to purchase seeds, equipment and other supplies.

Throughout the growing season, most residents and travelers in this part of the state drive by huge swaths of agricultural land. Many of these acres are devoted to commodity-scale corn and soybeans—planted, tended and harvested by machine—but other vegetables, destined for grocers, wholesalers and processors near and far, grow here too.

As apparent as the Garden State’s agricultural industry should be to anyone who’s ever tasted Jersey’s blueberries, sweet corn or tomatoes, the people responsible for that famous produce often remain invisible. The labor of the workers responsible for planting, tending, harvesting and packing the fresh produce in your salad is a hidden cost of large-scale produce production that’s being ignored at nearly every step of the supply chain. To maintain low food prices, farm owners here (as in much of the country) often push one of the only variable costs on their balance sheet—labor—as low as possible. Farmworkers are the ones who really pay for cheap produce—in the form of inadequate housing, low wages, workplace discrimination and harassment and long hours exposed to extreme temperatures and the harsh chemicals used in conventional agriculture.

CATA has been working with New Jersey workers to address these injustices since 1979. Originally founded by Puerto Rican farmworkers in the area, its constituents in the state’s agricultural regions are primarily Mexican, Guatemalan, Honduran and Puerto Rican. The organization is headquartered in Glassboro and works in six different agricultural counties in New Jersey; its efforts also extend out of state, to workers in southeast Pennsylvania’s mushroom-growing operations (where the group supports another farmworker-run community garden) and Maryland’s large chicken-processing plants. The organizers and board of directors are farmworkers themselves.

CATA organizers visit workers’ housing, which is often provided by farm owners but frequently falls short of federal and state standards, to run workshops on topics like workplace health and safety (such as the dangers of pesticide exposure or heat stress), workers’ rights and health issues, including HIV and STD prevention. During these sessions, farmworkers learn what labor violations look like, so they know when they’re being improperly treated.

As you might imagine, farm owners, even those who meet the lax legal minimums for farmworker treatment, are often uninterested in or hostile toward the idea of cooperating with CATA—even when it might save them time and money. For example, the organization’s Train the Trainer program, which CATA developed in collaboration with the Farmworker Association of Florida and the Border Agricultural Workers’ Project, has taught farmworkers to train others to conduct pesticide-safety trainings for the past decade. Farm owners are required by the federal government to train their workers in safe pesticide handling. In 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency, which sets standards and regulations for pesticide safety, revised these standards for the first time in two decades—requiring stricter practices, like training workers on pesticide handling every year instead of every five years. CATA sent letters to farm owners, as they have done in the past, offering to hold free trainings for them. As usual, there were no takers.

With the recent waves of interest in the organic and local food movements, consumers are becoming educated about the way their food is grown and how far the journey from field to fridge actually is. But farmworkers’ fight for rights like freedom from harassment, adequate living conditions and fair pay hasn’t taken hold of the public consciousness in the same way.

“[Farm work is] really invisible,” says Ramirez. During the growing season, farmworkers are often called in for as long as the light lasts— sometimes as early as 5 or 5 am to as late as 9 pm. “You go to the grocery store, you buy something, but you don’t really think about what’s behind all of that.”

It’s not just conventional or imported produce that casts a shadow over the supply chain. Certified organic standards for produce production, while limiting worker exposure to approved pesticides only, don’t address worker treatment, regardless of environmentally sustainable the growing methods are. In response to this lack, CATA, along with a coalition of other nonprofit entities and agricultural businesses operating as the Agricultural Justice Project, developed Food Justice Certified, a label with a high level of transparency that takes into account the labor practices around not just raw produce but also other ingredients added to processed products. The certification even examines the practices of companies that pack and distribute the products. Since the certification piloted in 2007, seven farms, artisans and other food businesses across the country have become certified—indicating how far our food system has to go before work in large-scale farming and food production guarantees fair treatment and a livable wage.

While not every member of the Bridgeton garden is a farmworker— as you might imagine, pulling 14-hour days doing anything isn’t really conducive to having the free time to garden—the project, providing fresh produce and green space, functions as an asset to its surrounding community. At the last census, 43 percent of Bridgeton’s residents identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino/a. The garden sits just two blocks east of the poorest census tract in New Jersey, south of Camden, where 61 percent of residents live below the national poverty line. With a high percentage of the downtown area’s residents working on farms for extremely low wages, this does not come as a surprise.

But the garden serves as an oasis of abundant, fresh produce in this community. A few dedicated members have their own raised beds, but most of the crops are planted, tended and harvested communally. Lettuce, cabbage, tomatoes, peppers, broccoli, cauliflower, Swiss chard, peas and beans are grown. Edible herbs also grow here, like lemongrass, cilantro and hoja santa, a broad-leafed plant with a slightly minty, anise-y taste that’s used in Mexican and Central American cuisines to flavor all manner of dishes. Perhaps the most prevalent crop across the garden is papalo, a piquant, leafy herb that’s planted among the vegetables. A full bed of it grows inside the greenhouse.

“It has a pretty strong flavor,” says Ramirez of the plant. “People don’t grow this back home [in Mexico]—it grows in the wild.” This variety, with slightly rounded, matte-green leaves that are smooth as suede, is particularly enjoyed in the southern Mexican states of Oaxaca and Puebla. It’s also known as summer cilantro for the tangy, peppery flavor that’s somewhat reminiscent of its spring-loving namesake. (It’s stronger in flavor, though, so use half as much papalo as cilantro when substituting in recipes.)

In addition to providing access to green and growing space and chemical-free produce at low or no cost to the community, CATA organizers hope to turn the garden into a hub for other activities. There are plans to add a small shade and seating structure in the front of the garden—“I feel like when people see the garden [as a place] just to come and work,” says Ramirez, “so we’re trying to create that space”—and plans are coming together to grow medicinal herbs in future seasons.

Last fall, a former CATA organizer turned clinical herbalist brought his students from New York to the garden to engage with community members. They held group consults on medicinal plants that can be used to treat common ailments like arthritis and diabetes, and went to a nearby park for a wild-plant walk, learning to identify local plants that can be used as home remedies.

Ramirez also hopes to attract more gardeners and shoppers to the Bridgeton garden. Gardener Migdalia brought lots of positive energy when she got involved, Ramirez says; some items on Migdalia’s long-term wish list are a shed out of which to sell products, a robust herbal-medicine program out of the greenhouse and “lots of people sharing.” For now, CATA and the Bridgeton Organic Community Garden will keep fighting for farmworkers’ rights—and making space for farmworkers to grow food that is truly their own.