Shared Meals, Shared Humanity

At the table with the Syria Supper Club

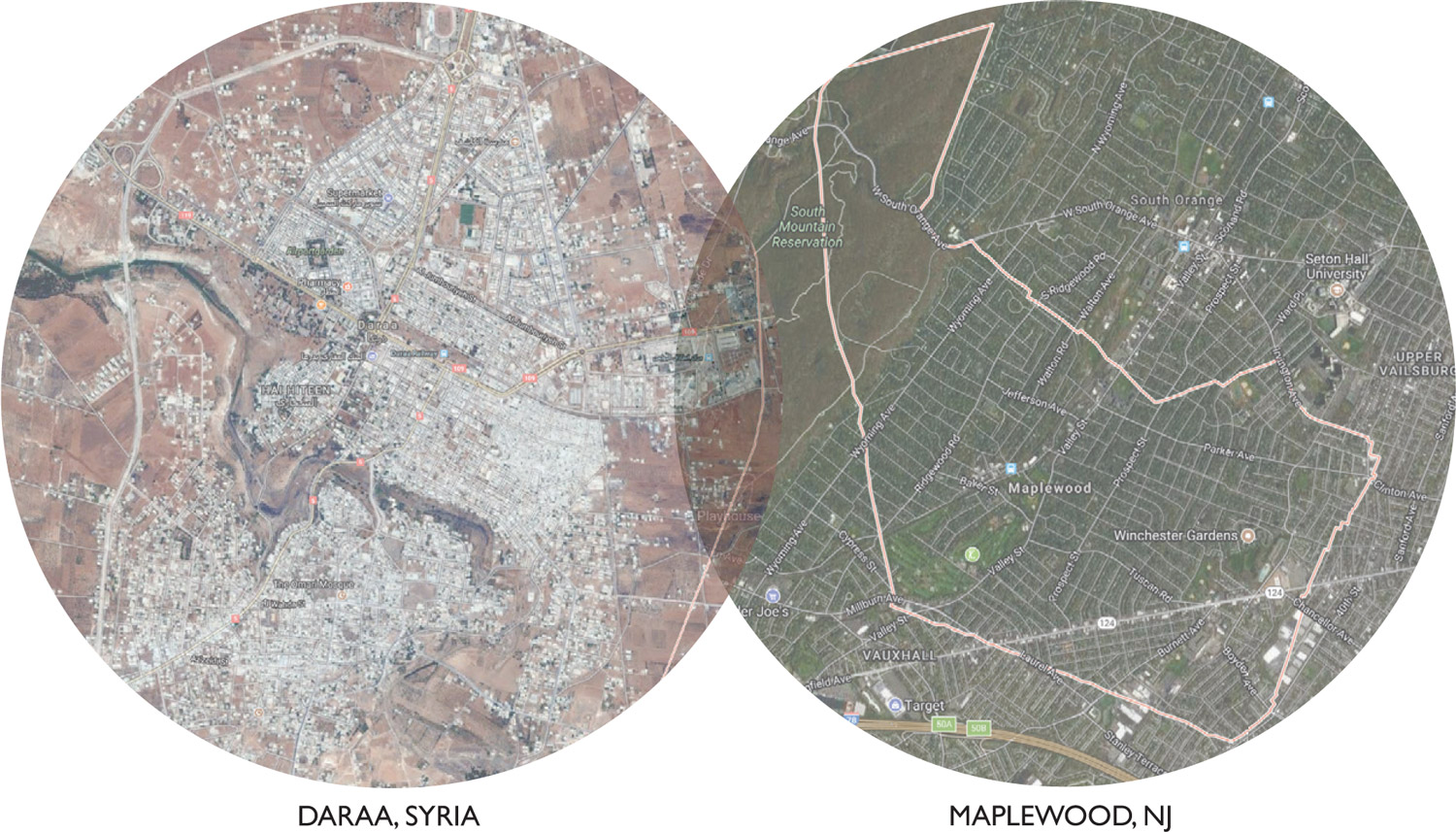

In the city of Daraa, in southwest Syria eight miles north of the Jordanian border, familial bonds have shaped communal rhythms for generations. Relatives typically lived in family compounds, where lines between kin and friend blurred. Generations shared knowledge and domiciles, sharing tables and stories amid the demands of daily life.

And strong community means feasts, for which Daraa is rightly famous.

Before the Syrian Civil War, wedding feasts featured enough food to feed a neighborhood. This is not hyperbole. Steaming platters of mujadara spanned entire table lengths, the savory rice pilaf dotted with brown lentils and caramelized onions. Platters were piled high with lamb or beef kofte, the delectable kebabs bright with sumac and seven-spice.

Coffee, perfumed with cardamom, flowed as generously as the conversation. Hospitality is a key cultural value in Syria, gorgeously expressed through food. Guests are considered a gift.

In recent years, such traditions have been interrupted. The spark for the Syrian Civil War ignited in Daraa in 2011, graffiti from a group of schoolchildren spiraling into a complex conflict with no end in sight. In the intervening years, nearly 80% of Daraa’s families have fled, according to nonprofit journalism organization Syria Direct. More than 11 million Syrians have been displaced internally or across borders.

Roughly 10,000 have been resettled as refugees in the United States. Many fled with few possessions. Kitchenware and mementos were left behind.

“A natural way to build

bridges, to break down

stereotypes, is to sit down

at a table.”

—Katherine McCaffrey

Today, however, Daraa native Maryam al Radi is giving new life to her traditions, and making a home in her adopted country. As part of Syria Supper Club, which has hosted events in North Jersey and Manhattan for more than a year, she is one of 40 Syrian cooks who are breaking bread with their new American neighbors and helping to support their families in the process.

Nearly every week, the cooks share pop-up meals at the homes of volunteer hosts, and sit to enjoy them side-by-side. This has struck a nerve. Since September of 2016, more than 2,000 guests have attended roughly 150 suppers.

The culinary heritage of Syria is remarkable: refined and deeply comforting. In part, it evokes the country’s location along the historic Silk Road, a confluence of influences and ingredients uniting to create harmony.

Persian, Asian, European and Ottoman notes united in gentle song, Syrian cuisine emphasizes balance—spiced, but never spicy. Lemon and pomegranate molasses offer flavorful bursts, sour meeting sweet. Onions are caramelized until they hit low tones, resonant and unctuous. Green parsley is sprinkled atop tahiniladen dips, awakening the palate. Syrian food is earthy. Syrian food is bright. Humble eggplant is elevated in dips that play with texture: mutabal is a form of baba ganoush, but looser.

Even when prepared for close family, meals in Syria are often quite elaborate, hours intersecting with skill to produce an array of dishes. This is certainly on display here. What appears to be an orange pepper is filled with flavored rice. Kubbeh, a fried bulgur- wheat dumpling shaped by hand, reveals savory ground beef inside. The meat is peppery and warm, comfort tinted with baharat, a spice mix redolent with cumin, coriander and cinnamon.

Syrian cuisine reflects an historic interplay of food cultures, all the while remaining distinctly its own. It also serves as an entry point by which to foster connection between communities.

PHOTOGRAPHS: GOOGLE EARTH

Breaking bread and building bridges

At 5pm on a late-summer Sunday, al Radi works with a sense of purpose in Katherine McCaffrey and Howard Fischer’s bright Maplewood kitchen. Against a backdrop of maroon-and-white patterned tile, nearly two dozen dishes are heated through and garnished as a stream of guests arrive. As she presents them, her well-earned pride rings clear.

“Two days, no sleep!” al Radi says. Her face breaks into smile easily, laughter serving as music as she works. Toward 6pm, guests filter in, cramming the kitchen and filling it with noise, as people do the world over. From a large Syrian family, al Radi knows how to prepare spreads with panache. “When I was 13, I cooked,” she says.

Her sisters married young, and al Radi helped prepare meals for her father and family. Fresh peppers, cumin and parsley are arranged in clever patterns, transforming hummus into a canvas. Tomatoes are carved into delicate roses. A deft hand with garnishes is a point of pride. “It’s very important to decorate everything,” al Radi says.

Noor, a Baghdad native and former geography teacher who prefers to keep her last name private, resettled here a year ago. She attends the dinner as a guest with her mother, Shuaa, and explains that such flourishes reflect a distinctly Middle Eastern culinary ethos. “In Arabic, every day, we remember this sentence,” she says. “‘The closest way to the heart is food.’” Some ideas are universal. As for the specifics, she says that Iraqi food is more protein-oriented. Yalanji, stuffed grape leaves, are a perfect example. “In Syria, the yalanji are just rice. In Iraq, meat,” Noor explains. The Syrian version is also smaller, slender like a finger.

Al Radi occasionally exclaims in Arabic, sharing knowing glances with McCaffrey, if not language. Much can still be expressed. Combine Google Translate and emphatic gesturing, and the two make themselves understood. It helps that al Radi and McCaffrey have easy rapport, a familiarity borne when people work together in the kitchen. This makes sense. McCaffrey, with Melina Macall, is the co-founder of Syria Supper Club, and she and Fischer have hosted more than a dozen dinners.

“All of them are different, and all of them are special,” Fischer says.

The origins of the series are found in a media moment during which harsh rhetoric regarding the refugee crisis has grown commonplace, in New Jersey and beyond. Outraged, Macall and McCaffrey, members of Bnai Keshet Synagogue in Montclair, wondered what they could do.

Seeing possibilities in partnership, Rabbi Elliott Teppermen united the pair. As it turns out, they were well positioned for impact. McCaffrey is an anthropology professor at Montclair State University, researching Latin American social movements and, more recently, refugee integration. Macall is a food-justice advocate, community gardener and founder of the Boxed Organics co-op who teaches at William Paterson University and has spent time studying the Cuban food system. Both see transformative potential in food.

In December 2015, McCaffrey and Macall partnered to organize their inaugural event at the synagogue, opening the door to Syrian Muslims for a Chinese “Jewish Christmas” feast. It drew more than 200 attendees. From there, they moved into fundraising, and as they got to know local Syrian families personally, they couldn’t help but notice that rich hospitality culture.

“I saw that everyone had china demitasse sets and china cabinets,” McCaffrey says. “They wanted to make coffee. They wanted to host and serve. That was super important to them, and this was a way of allowing them to take that on the road.” On Sept. 11, 2016, Macall hosted their first pop-up dinner. Al Radi, who came to the US four years ago with her husband, Fadel, and four children, was the cook.

Similar programs have emerged around the world.

The year that has passed since has been a whirlwind. Hundreds of dinners. A roster of cooks that has grown to include 40 women. Many hours of work for Macall and McCaffrey, on top of their day jobs—and clear hunger from a local audience for more of these kinds of experiences. Syria Supper Club was the first step. Now, Macall and McCaffrey are evolving into a newly minted organization dubbed United Tastes of America, which will expand on their mission of empowerment through food.

“I did a reckoning of all of the things I was interested in and involved in, and I realized they all had this common thread of food, but not just about making something,” Macall says. “It was always about food as a tool to bring people together. The running thread through all of this is collective power.”

Hospitality is a key cultural value in Syria, gorgeously expressed through food.

clockwise, from top left left: Yalanji (rice-stuffed grape leaves); Fattoush (with onion); Fasolia Bzait (green beans); Oven-roasted chicken and potatoes; Mutabal (eggplant dip)

clockwise from top left: Patrick Cox & Nicole Peterson (from New York City); Ses Spinelli, Milena Rubenstein, Eve Kingsbury (all of Maplewood); Mona Karim (of Maplewood); Noor, Shuaa (from Baghdad); Jules Greenwald, Howard Fischer (of Maplewood); Kate McCaffrey, Milena Rubenstein (of Maplewood)

Standing up by sitting down to dinner

In light of a wave of social unrest that has left many inspired to act, the Southern Poverty Law Center put together a publication entitled Ten Ways to Fight Hate: A Community Resource Guide. “All over the country people are fighting hate, standing up to promote tolerance and inclusion,” it reads. “More often than not, when hate flares up, good people rise up against it—often in greater numbers and with stronger voices.”

By McCaffrey’s accounting, the dinners cover the first three ways to fight hate: Act. Join Forces. Support the victims. (Here, perhaps, it is more like 20 dishes to fight hate.) Among the guests, a few are repeats, drawn by the fellowship as much as the food. “I love it. I love the food, Middle Eastern is one of my favorite foods,” says Maplewood local Ses Spinelli, gesturing toward the mutabal shawandar, the beet-and-tahini dip bright like a garnet. “This is a great opportunity. You get to learn about people.” She is a particular fan of foul moudamas, a fava dip she tried on her first visit.

As al Radi finishes the preparation, the group gathers for formal introductions, and McCaffrey sets the tone. “Our goal is to bring people together and to celebrate our commonalities,” she says. Al Radi follows: “Thank you for coming for our food.” She notes what the experience means to her family, and explains that this is a humble reflection of her country’s food (though it certainly does not seem this way). Back home, ingredients like feta cheese were much more affordable, so she used them freely. She is shocked by American food prices.

By design, the Syria Supper Club menu is vegetable-forward, meat reserved for a few dishes. Cooks are given a set amount based on the number of guests, and then are free to use the budget as they see fit, keeping the rest. The dinners offer a chance to reconnect to a social food culture, and to find creative ways to recreate flavors. In the process, the cooks enjoy autonomy, an underlying goal. “She did this,” McCaffrey says. “I didn’t tell her what to cook. I didn’t tell her what to buy. I told her 20 people.”

“This is the second dinner I’ve been to. I really liked the first one,” says Sam Spinelli, Ses’s husband. “I come from a family of immigrants. I’m the first generation. Not quite the same as what these people are going through, but I really feel for you and I’m really happy to be here.” “It’s a beautiful table,” says Harvey Rubenstein. “I’m so looking forward to enjoying the food, meeting you and understanding all that you put into the food. We hope to learn from it, and try to do some ourselves.”

While blanket and clothing drives are well meaning,

McCaffrey and Macall want to shift the nature of

refugee outreach and move away from the common

narrative of victimhood and toward dignity.

As people begin to eat, a temporary hush. Nothing quiets a crowd like skilled cooking.

“Delicious, delicious, delicious,” says Milena Rubenstein, smiling across the table at al Radi as she tastes the roasted chicken. But it is the harra bi isbaou—a sweet-sour lentil stew with tart pops of tamarind—that captures her imagination. “Wow, it’s like a little surprise,” she says.

Ultimately, the dinners serve two constituencies. The cooks have a platform by which to showcase their talents, often overshadowed during resettlement. “The second is the Americans who are appalled at what is going on at the national level [in terms of the US response to refugee immigration] and really want the opportunity to do something locally to express their values,” McCaffrey says. “The Americans need it just as much as the Syrians do.”

Macall agrees. “What can we do that’s positive?” she says. “This is not how we want a human being to be treated, in New Jersey in particular. That has resonated for many of our guests. I think they feel that this is an opportunity to say: That’s not my America. That’s not what I believe in.”

The best nights are those during which the guests do not know one another beforehand. “They’re coming forward and saying, ‘I’m going to go to a dinner with people who I don’t know at all because I really want to meet these people, support them, be a part of this,’” McCaffrey says. “Those people tend to be more curious and engaged.”

That being said, curiosity can be double-edged.

Sometimes, people feel entitled to ask questions about the Syrian cooks’ experiences that would never fly in another setting. This is a point that McCaffrey and Macall are working on as the organization evolves. While most Americans experience the war in the form of headlines—in other words, from a distance—it is visceral for the displaced.

It is also present tense, recounted daily via messages from those back home. Where Americans talk about technology impeding relationships, cell phones are a consistent link for scattered Syrian families. “When you go to the refugee camps and get asylum somewhere, you don’t pick where you want to go,” Fischer says. “You may go here. Other members of your family may go to Germany. Others Canada. So, your family ends up not only across the world, but also left in Syria.” This can be a good thing, but worries quickly travel.

Resettlement can be its own form of trauma, requiring years of effort, grit and a demand to recount their most painful story many times over. A litany of office visits and awaiting forms await, all in a new language. Refugees are learning a new social context, and rebuilding lives far from home. Moreover, they begin in debt, required to pay back relocation costs to the government. For the al Radis and their four children, that amounted to $7,000, for which McCaffrey and Macall launched a fundraiser.

This would all be daunting to the average New Jersey family. Add in the complexities of starting over in a new culture, and it can seem insurmountable.

“If you know someone who just had a painful divorce, you don’t walk up to them and go, ‘Hello, nice to meet you. I understand you had a painful divorce, now tell me all of the details,’” Macall says. “You would never do that. And yet people have no compunction walking up to someone and saying, ‘Tell me your story.’ They don’t see that it’s the same thing. If they want to share their story, it’s entirely up to them—but it should come from them, not from us.”

To redirect the narrative, Syria Supper Club emphasizes an inperson experience of our shared humanity. All one needs to attend is an open mind. “Some people felt worried about coming because they didn’t know enough,” McCaffrey says. “They felt like they needed to have read a book on Syrian history in order to interact at a table with somebody, which kind of shows how isolated we are.” One dinner at a time, she hopes to change that.

Shuaa and Katherine McCaffrey using “Google Translate” on an iPhone

Shaking up the narrative

While blanket and clothing drives are well meaning, McCaffrey and Macall want to shift the nature of refugee outreach and move away from the common narrative of victimhood and toward dignity. Given the success of Syria Supper Club, they are also thinking bigger. As they evolve into the newly incorporated organization dubbed United Tastes of America and seek nonprofit status, they envision a formalized catering program, cooking classes and new programming that incorporates an array of cultures.

“We started with the Syrian community because we were reacting to the Islamophobia,” McCaffrey says. “A natural way to build bridges, to break down stereotypes, is to sit down at a table.” In time, they hope to create a template that other communities can leverage.

This idea has taken off in other parts of the world, including in Toronto, where a program dubbed Newcomer Kitchen has similar aims. As refugees resettled there, Depanneur, a culinary food venue with a global bent, opened up its kitchens so that women housed in hotel rooms had a place to cook. Some hadn’t had access to a true kitchen for years.

What started as a communal cooking project for the women evolved into a weekly pop-up that offers Syrian meals for pick-up or delivery. “We knew the pennies were the real crisis for them,” says co-founder and project director Cara Benjamin-Pace. “We thought, why don’t we pack up the food we made? You take some home and we’ll sell the rest. We tried it, and the first day sold out immediately.” Among their happy customers? Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Benjamin-Pace sees programs like these as a way for participants to earn extra income, while making a home in their new countries. It is also about moving women from the informal to the formal economy. Benjamin-Pace and her co-founder, Len Senater, have been able to hire 16 part-time employees. They are also working with the Young Leaders Program of Deloitte, the multinational financial services firm, to develop their strategic plan, and have started catering for its in-house café.

“It’s about integration, but also bringing in their own identity, efficacy and womanhood,” Benjamin-Pace says. “We want them to understand that they are fundamentally wanted in this community.” The key question moving forward is: “How do communities develop models for successful integration into the job economy that also recognizes the challenges and works to amplify the talents that they bring?”

McCaffrey and Macall are on a similar path, seeking to find the answer that makes sense here in New Jersey.

“We want to professionalize this. We want a professional kitchen. We want professional certification for everybody so we can do professional catering and professional things,” Macall says. That’s a recipe with much potential: Collective power plus gorgeous food leads to new understanding and opportunity—a true social enterprise.

Over several hours at McCaffrey’s home, conversation hums over parsley-laden fattoush salad and oven-roasted chicken. Curiosity gives way to familiarity, food working its unique magic to unite people. Al Radi’s stuffed cabbage, it turns out, looks just like that which Fischer’s mother makes. “Send my mother a picture!” he says.

“There is a collective power with all of our guests coming together to stand united with our newest neighbors and show support in a way that doesn’t reinforce victimhood, but promotes dignity,” Macall says. “I remember one of the cooks saying that she loves coming to this because when she comes, she is not judged, she’s just a person. You’re finally just a person, no matter where you come from or who you are.”

As the guests filter home, offering their compliments to the cook, McCaffrey brews coffee. Al Radi says her hope is that Americans who attend the dinners will take away a new view of Syrian culture. “In our culture, everyone can come to the home for large dinners,” she says. “We like when people come for any meal, in the morning, anytime. We like when people come on all of the days.”

“It’s very important,” Noor adds. “I think that’s not as important in America.” Al Radi’s husband, Fadel, chimes in: “Here, just Kate (McCaffrey).”

Ever the hostess, al Radi offers her seat at the center island, but she has more than earned it. She nestles in alongside Noor and Shuaa, and finally—blissfully—calls the evening complete. The dialogue again grows familiar, English phrases swirling between the Arabic. If there is proof in the power of food to forge bonds, it is most clearly seen here: a small group of women from Syria, Iraq and the US celebrating another successful dinner over sweet dates, hot coffee and warm conversation.

Bread stuffed with tomato and herbs

MARYAM AL RADI’S MENU FOR A SYRIAN FEAST

- Mutabal shawandar: Syrian beet-and-tahini dip

- Fattoush: Parsley, tomato and pita salad with an olive oil, lemon and pomegranate molasses dressing

- Hummus: A classic Middle-Eastern dip made with chickpeas and tahini

- Mujadara: Rice and lentil pilaf with caramelized onions

- Harra bi isbaou: A sweet-and-sour stew of lentils and small pieces of bread, flavored with tamarind, lemon juice, garlic and cilantro

- Peppers: Stuffed with savory spiced rice

- Yalanji: Rice-stuffed grape leaves, similar to dolma, but thinner

- Fasolia bzait: Stewed green beans with tomato, a Syrian favorite

- Mutabal: An eggplant dip similar to baba ganoush, but with a looser texture

- Kubbeh: Bulgur wheat dumplings filled with seasoned ground beef

- Falafel: Fried chickpea patties

- Mihshai malfoof: Cabbage rolls stuffed with seasoned rice

- Chicken and potatoes: Oven roasted

- Fatayer sabanekh and jebheh: Spinach and cheese pastry triangles

- Bread stuffed with tomato and herbs

- Mehshi basal: Leeks and onions filled with vegetable-flecked rice

- Riz b’ shar’riya: Rice with toasted noodles

- Bami: Okra soup, made with potato and carrot and meant to be served over rice

- Pitas

GET INVOLVED

Globally, the United Nations Refugee Agency estimates that 20 people were displaced from their homes every minute in 2016. Here are a few ways in which you can make a difference.

- United Tastes of America / Syria Supper Club (SyriaSupperClub.org): Attend a dinner. Then, if you are within an hour radius of Elizabeth, consider hosting one yourself. In-kind and monetary donations are being sought to advance the organization’s expansion.

- UNHCR—The UN Refugee Agency (unhcr.org): From emergency assistance to global advocacy, UNHCR assists refugees and displaced people around the world. Their website offers up-to-date information on the refugee crisis and ways to help.

- IRC—International Rescue Committee (rescue.org): Volunteer programs focus on community integration, from mentoring to job training.

- Needs List (needslist.co): Launched in Philadelphia this past summer, Needs List links NGOs with individual and corporate donors. With a click, you can donate kitchenware to refugee camps or school supplies to children.

- Faith communities: Faith communities have taken a leadership position in helping refugees get established. The Church World Service also advertises opportunities. Ask your local mosque, synagogue or parish if there are programs in place.

Maryam Al Radi (who did not want her face photographed) at work in the kitchen

SYRIAN COOKBOOKS

Al Radi has a bit of advice for Americans who wish to try their hand at Syrian cuisine: “Everything is step by step.” These cookbooks offer a good start.

Flavours of Aleppo: Celebrating Syrian Cuisine

Dalal Kade-Badra and Elie Badra (Whitecap Books, 2013)

In their Montreal kitchen, a Syrian mother and son pay tribute to family dishes from Aleppo.

Cook for Syria

Serena Gruen (editor) (Suitcase Media International, 2017)

Connected to a UK-based international fundraising initiative, the book includes recipes from Syrian families and globally renowned chefs.

Our Syria: Recipes from Home

Dina Mousawi, Itab Azzam (Running Press, 2017)

Recipes collected from Syrian cooks in the Middle East and Europe showcase the country’s vibrant food.

Sitto’s Kitchen: A Treasury of Family Recipes Taught from Mother to Daughter for Over 100 Years

Janice Jweid Reed (Dog Ear Publishing, 2012)

A Syrian granddaughter works through her grandmother’s spiral-bound recipe book.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Also Soup for Syria, Barbara Abdeni Massaad (Interlink, 2015), profiled in Edible Jersey, Winter 2016 issue.