Her Own Beet

Memories of Poland resonate in Martyna Krowicka’s cuisine

Martyna Krowicka knows that beets belong in borscht.

At three years old, in her native Poland, she protested what she considered an inadequate number of beets in her own grandmother’s recipe. Mind you, the borscht contained beets. You can’t get that jewel-toned broth without them. But her grandmother had left out the big chunks, thinking they would not appeal to a toddler’s taste.

How wrong she was.

Picture an indignant three-year-old, railing against this culinary injustice. Chubby fists clenched, mouth in an outraged “O.” Her tear-stained face, beet-red. Or maybe she presented her complaints with lawyerly detachment, outlining the charges and making a firm case for where the recipe went wrong. Who’s to say, for sure? Family lore can change, decade by decade.

Martyna Krowicka and her mother, Agata Krowicka, can laugh about it now. The grown-ups in the family laughed about it back then, too. It is the kind of story relatives tell about you when they’re proud of you, so they can say, “She was never finicky, that one. And she didn’t want her food dumbed down.”

As head chef at the acclaimed Restaurant Latour at Crystal Springs Resort in Hamburg, Krowicka uses her appreciation for down-to-earth, farm-fresh food in an elevated setting. She proved her mettle on a different platform as a contestant on the Food Network series Chopped, winning the farm-to-table episode “Betting on the Farm,” which aired December 15, 2016.

Before joining Latour, Krowicka was sous chef at the Ryland Inn in Whitehouse Station. She is a 2009 graduate of the French Culinary Institute in Manhattan. But Krowicka doesn’t think a degree is the end-all, be-all. She believes that first and foremost, aspiring chefs need to love food. They need to feel connected to ingredients. They need to feel passionate enough to throw a fit over borscht.

“My grandmother made a hearty borscht,” Krowicka says now, re-evaluating her crusade for more beets. “It was just that there were no chunks, and I loved eating beets, and I can remember yelling at her, at all of three years old.”

Recipes change

over the generations.

Sometimes a non-traditional

ingredient will land in

Krowicka’s Polish food.

At other times,

a Polish accent can be found

in the food she makes at

Restaurant Latour.

This is one of Krowicka’s earliest memories, and one of the few she has from before she left the village of Pilawa in the Lower Silesia region of Poland in 1992, at the age of four. Most of the knowledge she has of the country in which she was born comes from summertime visits with her grandmothers and from family recipes, passed along like relics. A well-worn 1988 hardcover Polish-language edition of Kachina Polska, a cookbook by Hanna Szymanderska, is kept at the ready in the family kitchen. Like many an immigrant child, Krowicka stays connected to her homeland through language, customs and food.

The late Paulina Szydlowska was Martyna’s maternal grandmother, the one with the beets. She died in the summer of 1988, when Martyna was 10. The late Gienia Krowicka was Martyna’s paternal grandmother, on whose farm Martyna’s family lived before immigrating to the United States. She died in 2014, when her granddaughter’s career already was on the rise, but she was too sick in her final years to understand. Would these women be astonished to learn that their granddaughter has become an accomplished chef? Or would they nod knowingly and say, “Our Martyna was not one to cut corners. Remember that time with the borscht?”

Krowicka lives with her parents, Agata and Kazik, and older sister, Olga, in her childhood home in Roselle Park, a Union County town in an area with a strong Eastern European presence. Of the family’s three dogs, two of them mill about the kitchen—a mellow Golden Lab named Walter and a curious pit bull mix named Chica. The dogs know where the action is, and they wag expectantly as Agata and Martyna work together at the stove.

On a weekday afternoon, mother and daughter are in their cozy kitchen, with copper mugs hanging on the wall, curtains depicting wine bottles and bunches of grapes, and a collection of eccentric antique gadgets, including an absinthe drip and a Delft coffee grinder. They are demonstrating the making of krokiety, a breaded crepe filled with mushrooms and sauerkraut.

“It’s so Polish,” Krowicka says. “Pierogi are just Eastern European, because lots of countries claim them. But I personally haven’t seen krokiety from any other nationality.”

She and her mom take turns dipping the wheat-flour crepes into a bowl of raw eggs and sizzling them in a pan. Krowicka works quickly.

“You ripped one,” her mother points out, but Krowicka folds the crepe around the filling. It is none the worse for wear.

“We brown it, and add crumbs for texture,” Krowicka says.

“Sometimes, they come out too tender,” her mom says, explaining the torn crepe.

“That’s because we don’t have a written recipe,” Krowicka adds.

“It is a must-have for Christmas Eve,” her mother says, noting that they also serve a clear borscht in tea cups, without the usual beans and potatoes that make up the hearty everyday version of the soup.

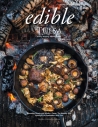

top to bottom: Krokiety, a breaded crepe filled with mushrooms and sauerkraut; Salatka, a potato salad, with hard-boiled eggs, carrots, peas and pickles; Sweets include jablecznik, an apple cake, and makowiec, a poppy strudel

Polish traditions influence celebrations all year in the Krowicka home. On Easter, they bring hard-boiled eggs to church to be blessed, then serve them at home for breakfast with bread and bilawa kielbasa, a white sausage.

“In summer, we are more Americanized,” Krowicka says. “We have ribs and we grill sausage, with a Polish cucumber salad, with sour cream and salt and pepper.”

The Krowickas host Thanksgiving every year, with a mish-mash of a menu, blending American and Polish foods. “It’s the one holiday that had no meaning for us in Poland,” Krowicka says. They are creating Thanksgiving traditions as they go along.

At any time of year, hospitality is paramount. “If we invite someone for coffee or tea, there is always cake,” Krowicka says. “And often there are plates of cold cuts, other meat and cheeses.”

The Krowicka women lead their guests into the dining room to sample the krokiety. On the table are also salatka, a potato salad with chopped hard-boiled eggs, carrots, peas and pickles; and a platter of jablecznik, an apple cake, and makowiec, a poppy streudel.

All the dishes are homey and tasty, but the makowiec stands out. It is beautiful to look at, with poppy seeds packed into the layered pastry, and it is rich in taste and texture. It is Krowicka’s own take on a Polish dessert. She explains that the glaze includes Meyer lemons.

“What are Meyer lemons?” her mom wants to know.

Later, Krowicka illuminates her choice of lemons.

“It is traditional to use lemon in the glaze,” she says, “and I happen to really like Meyers. They’re sour, fruity and floral.”

Recipes, she says, do change over the generations. And it works both ways. Sometimes, as with the Meyer lemons, a non-traditional ingredient will land in Krowicka’s Polish food. And at other times, a Polish accent can be found in the food she makes at Restaurant Latour.

At the restaurant, Krowicka makes her own butter, crème fraîche and yogurt, “in keeping with tradition from home.” If guests aren’t able to pinpoint that as a Polish influence, they will at least sense that some extra care has gone into the preparation, and that is gratifying to Krowicka.

Anthony Bucco, executive chef at Restaurant Latour, hired Krowicka in 2015. He has been a mentor to her for years, beginning at his own restaurant, Uproot, in Warren, and then at Ryland Inn. His first impression of his protégée was that she was humble and quiet. Then he discovered she was also talented and as tough as nails.

“She has no issues with getting her hands dirty, and working hard, and dealing with the heat of the kitchen and the stress and dealing with the expectations of customers and chefs,” Bucco says. “She has a flair for creativity, and she takes incredible pride in being able to handle ingredients.”

In her home cooking, Krowicka is a traditionalist in some ways.

“There are certain dishes that need to have specific side dishes,” she says. “For example, pork cutlets need to have mashed potatoes with dill and grated beets or cucumber and sour cream salad. Stuffed cabbage needs to be with tomato sauce. Pierogi need to be with fried onions and bacon.”

And there are some things about Poland that are out of reach. Dairy products available to Krowicka here don’t quite match up to what she’d be able to get in Poland, which is why she makes her own. Then there are things from Poland she cannot duplicate.

“I miss the mushrooms,” she says.

In the rural Southwest corner of Poland, close to the border of Germany and the Czech Republic, there are deep forests. The locals know where to find the best mushrooms, to be eaten fresh or to be dried, for use in krokiety or pierogi or any number of dishes. Mushroom hunting is a pastime in Poland, and is celebrated in several passages of the national epic poem of Poland, “Pan Tadeusz,” or “Sir Thaddeus,” written in 1834 by Adam Mickiewicz.

Mushroom varieties, such as boletus, are name-checked in the poem, as in this passage:

From the grove comes the whole company,

carrying all variously, caskets,

Kerchiefs knotted at corners, or small wicker baskets

Full of mushrooms; young ladies displayed in one hand

The imposing boletus, a well-folded fan,

In the other hand, tied like a field-flower posy,

Carried tree-and-mulch mushrooms, brown, ochre, and rosy.

Krowicka tries her best to duplicate this recreational tradition.

“I do forage for mushrooms and dry them for the winter,” she says. “Morels grow wild at Crystal Springs, and I’ve used them.”

It’s not the same as having a forest to wander through. But it is a pragmatic response to a romantic memory. Krowicka brings the Poland of her imagination into her work whenever she can.

“What shapes the chef is their experience in life, in general,” Bucco says. “Are you, the chef, letting your experiences resonate through your hands? If so, your ingredients will tell your story for you.

Martyna (right) with her mother, Agata

Finding Poland in New Jersey

When Agata Krowicka bakes, she uses Polish flour

Is it any different than American brands of flour?

Not really, she’ll admit, but says, “It’s what I’ve always used, so I like it.”

The concept of comfort food extends to the brands that are familiar to us. For immigrants such as Agata, who left Poland in 1992 to settle in New Jersey with her husband and daughters, ethnic grocery stores, delis and bakeries connect them to the old country

Peek into the Krowicka family’s refrigerator in Roselle Park and you’ll see bottles of ordinary American condiments such as ketchup, mustard and mayonnaise. But while the packaging resembles those of Heinz, Gulden’s and Hellmann’s, the brand names are different: Kamis for ketchup and mustard, Winiary for mayonnaise. They are from Poland.

To find these goods, the Krowickas need only go to their local Polish grocery store, Syrena Polish Deli in nearby Linden.

It is here where the Krowickas can buy Masa Makowa, a popular brand of poppy seed filling, when they don’t have time to make it from scratch. Or Cracovia pickles, to accompany the cold cuts and varieties of Polish sausage they get from the deli counter at Syrena.

Customers who wait in line to pay for their groceries might find themselves checking out the Polish sports apparel that hangs on the wall behind the cash register. Or they might pick up some of the European chocolates that tantalize from the nearby shelves.

Martyna Krowicka, a chef who is the daughter of Agata, is often tempted by the Kinder brand of chocolates, a subsidiary of the Italian brand Ferrero. Maybe with a creamy filing, or with hazelnut? Far more exotic than your usual Snickers bar:

Her mom reaches for a bottle of Cracovia raspberry syrup. “It’s a good cold remedy in winter;” Agata Krowicka says. “You add it to sparkling water or tea. Plus it tastes good.”

The family does not do all their shopping at places like Syrena. But there is something neighborly and comforting about browsing the narrow aisles of an ethnic grocery store. For immigrants, it’s a reminder of their old home. For others, it’s a peek into a different world, a trip to a faraway village, without needing to take flight.

Martyna Krowicka recommends the following businesses for authentic Polish fare:

SYRENA POLISH DELI

1117 West Georges Ave., Linden

908.486.0677

(also on Facebook)

“We buy our canned goods, jams, meats, flour; all our staples here,” Krowicka says. A go-to deli for the Polish community since 2001. Known for take-out and catering, especially at Easter and Christmas.

DELICIOUS FRESH PIEROGI

594 Chestnut St., Roselle Park

908.245.0550

freshpierogi.com

“As close as you’re going to get to traditional pierogi,” Krowicka says. Founded by a Polish immigrant, Richard Jackiewicz, in 1991, Delicious Fresh Pierogi products are now sold in most major supermarkets throughout New Jersey, including Shop-Rite, Stop & Shop, Whole Foods, Kings, Acme and C-Town. The pierogi are made daily and sold fresh. They are egg-free, low in fat and certified Kosher Varieties are potato; cottage cheese; potato and cottage cheese; potato and Cheddar; potato and mushroom; potato and spinach; sauerkraut; potato and sauerkraut; sauerkraut and mushroom; mini potato and onion; and potato, Cheddar and jalapeno.

BIEDRONKA

1025 West St. Georges Ave., Linden

908.583.5409

“Polish deli and supermarket, larger store with more ingredients,” Krowicka says. “Essentials that you’d find in Poland.”

Homemade meats and Polish specialties and deli items, sundries.

POLONIA BAKERY

204 Monroe St., Passaic

973.471.3485

poloniabakery.com

“The best paczki, in all of New Jersey,” Krowicka says. Founded in 1953 by Jan Kaczmarek, Polonia Bakery is now run by his son, Andrew. Specialties include babka, poppy seed cake, rye bread, strudel, pierogi and its signature item, paczki, a Polish jelly donut.

Polonia Bakery also makes wedding cakes. Easter specials are offered each year.

ABIGAIL’S CAFÉ

804 West Elizabeth Ave., Linden

908.523.0777

abigailscafe.com (also on Facebook)

“Polish/Portuguese restaurant with authentic Polish and Portuguese food,” Krowicka says. “Not a fusion. All separate.”

Established in 2008, Abigail’s Cafe has a menu that covers much of Europe, from paella to pierogi, with stops in between for American classics. The restaurant also offers steak-on-a-stone.

Open for lunch and dinner Catering available.

And here are a few more Polish places to check out in other areas of New Jersey:

EUROPEAN HOMEMADE PROVISIONS

301 Old Bridge Turnpike, East Brunswick

732.254.7156

europeanhomemadeprovisions.com (also on Facebook)

Festively decorated all year ‘round, but especially glittery at Easter and Christmastime, when foil-wrapped chocolates and be-rib-boned packages of baked goods line the shelves.

At Easter, the Eastern European specialty store sells painted wooden eggs in Ukrainian, Slovak and Polish styles, along with egg dyes and Easter cards in many European languages. Catering is available.

European Homemade Provisions has its own smokehouse, and specialties include housemade hams, kielbasy and other meats. The well-stocked deli offers salads, including a popular chicken salad with grapes. Pastries, breads, pierogi, fresh horseradish and imported grocery items are also sold.

Established in 1955, European Homemade Provisions is a Middlesex County treasure with an old-timey feel. No credit cards are accepted. Bring plenty of cash for all those impulse buys.

KRAKOWIAK RESTAURANT

42 Main St., South River

732.238.0433

krakowiakrestaurant.com

Named after a Polish dance style from the city of Krakow, this little restaurant in downtown South River serves Middlesex County’s Polish community and everyone else who likes homemade pierogi, bigos, ghoulash and golabki at reasonable prices. Open for lunch and dinner; take-out and catering.

PIAST MEATS & PROVISIONS

I Passaic St., Garfield

888.742.7887

piast.com

Founded in 1991 by Polish immigrants Henry and Maria Rybak. The store has two additional locations, serving Bergen and Essex counties: 800 River D r in Garfield and 1899 Springfield Ave. in Maplewood.

Pierogi, kielbasa, cold cuts, cheeses, baked goods, groceries and hot foods.

HALINKA POLISH DELI

438 Route 206 South, Hillsborough

908.829.3271

polishdelinj.com

Pierogi, stuffed cabbage, sauerkraut stew, Polish pastries and more. Hot lunch items available daily. Catering menu.

SILS PIEROGI & MORE

1071 Route 37 West, Suite 5, Toms River

732.575.7218

silspierogi.com (also on Facebook)

Pierogi are hand-pinched daily, including seasonal and dessert varieties. Homemade soups, comfort food and Eastern European specialties. Lunch specials.