Beyond Pretty: The Beauty of Regenerative Gardening

Like me, you may well have been practicing regenerative gardening at home, but didn’t have a name for it. It’s a more ecologically conscious way of gardening: nourishing the soil naturally by not raking leaves in the fall; planting densely, which keeps the weeds down without having to re-mulch every spring; and planting to attract pollinators and birds. All told, doing less to disturb the natural cycle.

If you’re ready to take your regenerative gardening to the next level, here are some ideas I ’ve been exploring in my garden:

“IN THE PAST, WE HAVE ASKED ONE THING OF OUR GARDENS: THAT THEY BE PRETTY. NOW THEY HAVE TO SUPPORT LIFE, SEQUESTER CARBON, FEED POLLINATORS AND MANAGE WATER.”

Electrify your maintenance equipment. Converting most or all of your garden equipment, such as your mower, blower, and weed whacker, from petroleum-fueled to electric is quieter and lighter. What’s more, you can get rid of the gas can in the garage. Today’s electric equipment requires less energy to do the same amount of work.

Compost. Small suburban homes don’t always allow us to do all we want. I’d love to have a three-bin composting area, but for now I compost in a tumbler on my driveway. It allows me to compost mostly food waste, but not the debris I trim and weed from my garden all season long. Lucky for me, here in Morristown we have a great recycling center, where I can dispose of my yard waste for free, and pick up mulch or compost when needed. Composting is a way to bring less in and take less out of your property. Keeping everything on site to use is a great goal.

Reuse materials. A while ago, I asked a neighbor who was replacing their driveway to deliver the old, broken-up concrete to my house. The back 25 feet of my property was slightly raised and I always wanted a wall there, to create a new garden area. We broke up the pieces even more and used them to build a low wall along the back of the property. The concrete would have been taken to a concrete recycling plant, but we saved a lot of energy by not having it hauled away. When replacing a concrete front walk with a bluestone walk for a client, we did the same thing: broke up the concrete into manageable pieces and used them as stepping stones around the outside of the house. Implementing ideas like this can avoid hauling material in and out, lowering your carbon footprint.

Upcycle. Cradle-to-cradle is a term that architect William McDonough uses in his 2002 book of the same name. Instead of cradle-to-grave, in which we landfill items when we’re done with them, cradle-to-cradle, or upcycling, means putting everything back into production at the end of its useful life, so it never gets landfilled. The pergola Max and I built, above my concrete “stone” wall, is steel. We welded it in place on site. At any time in the future, when the next owner of this home decides to get rid of it, it can be 100 percent recycled. Steel is a great material for that reason. The problem with a lot of the engineered wood people use so much of today is that it is wood mixed with something else, usually plastic. Yes, the plastic was recycled, but now it is a dead end; it will end up in a landfill when its current use is finished because it cannot be separated from the wood. Think of using 100 percent plastic for your outdoor furniture instead of the plastic/wood mix. Use a wood fence instead of PVC, which will never be recycled.

Mow less. Do you really need all that lawn? We quit mowing most of ours many years ago, and the amount of wildlife we’ve seen since has increased tremendously. The meadows that result are like forest edges; they are home to hundreds of species of birds, reptiles, insects, and small mammals. They are also carbon sinks, absorbing and holding carbon underground. The deep roots of most native meadow plants help with water infiltration, more important than ever with our new patterns of heavy storms.

Layer your garden like a lasagna. Planting into an established meadow is tough; there is a lot of competition with the existing root mass. So try “lasagna gardening”: Cut a small area very short, then layer it with large pieces of cardboard and another layer of mulch. Wet this down and, in about a week’s time, plant some small plants. (I planted native hibiscus, Joe-Pye weed and cardinal flower, to name a few.) Be sure to cut holes through the cardboard so the roots can reach the soil when you do this. The cardboard will smother the existing vegetation, giving the new plantings a fighting chance.

Hügel at Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia

DO YOU REALLY NEED ALL THAT LAWN? WE QUIT MOWING MOST OF OURS MANY YEARS AGO, AND THE AMOUNT OF WILDLIFE WE’VE SEEN SINCE HAS INCREASED TREMENDOUSLY.

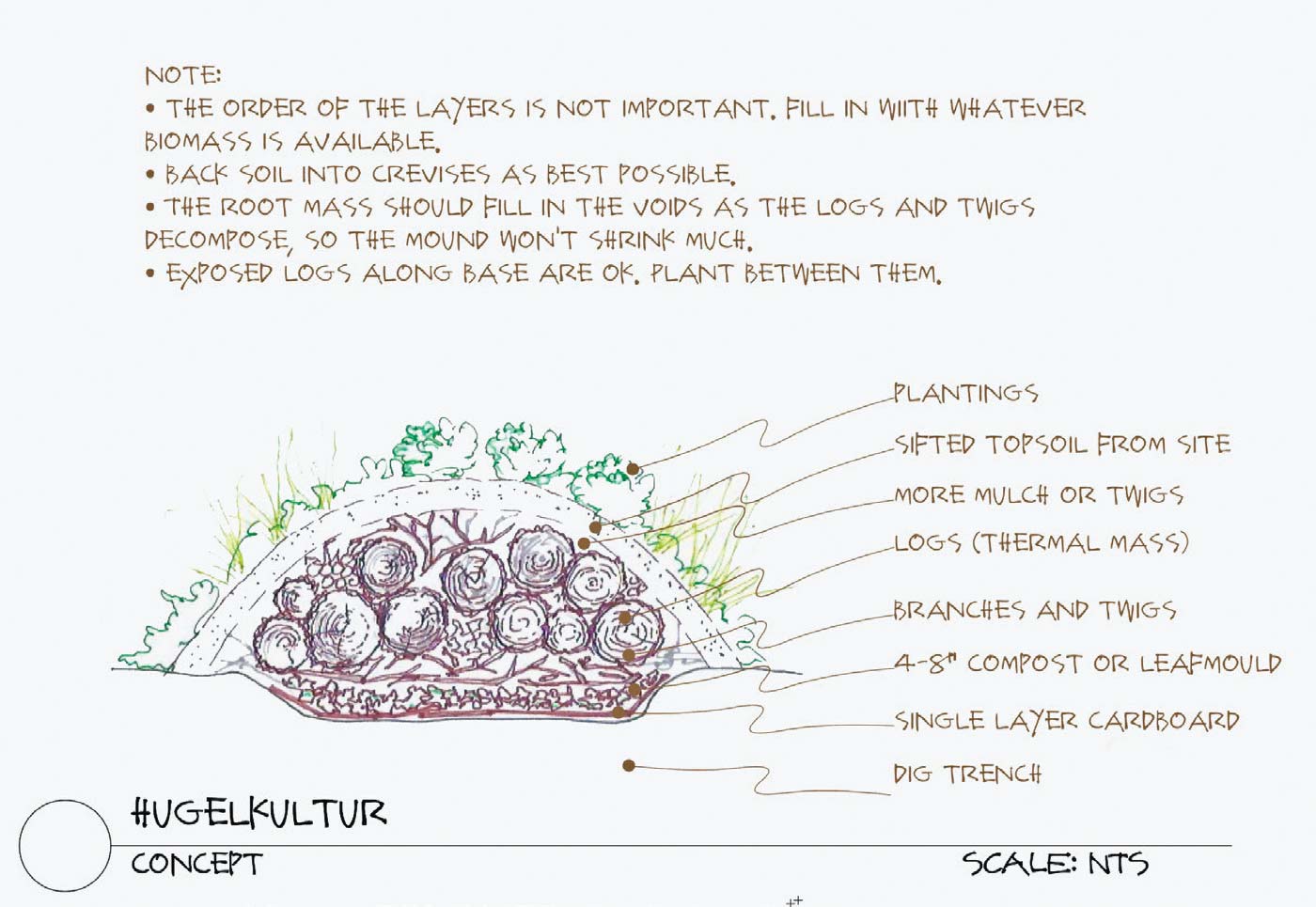

Practice hügelkultur. The term hügelkultur, German for mound culture, refers to an old European technique that is being revitalized as a sustainable solution for regenerative gardening.

A hugel starts with a small depression in the ground. To this, add a layer of cardboard, which will be a food source for mycorrhiza, a beneficial fungus that grows symbiotically with roots and provides a head start to future plantings on the hugel. Over the cardboard, layer some compost, mulch, woodchips, and any compostable biomass (organic matter) you have. Then add small and large logs, topsoil, and finally your plantings.

Hugels are sometimes used for growing food, but in our case we were left with many felled trees after the power company came through, and rather than burn or chip them, we bound them in a hugel, creating a carbon sink. And where there is carbon in the soil, there is water, and life. And as this hugel matures and biodegrades, it will heat up earlier in the spring and give the plants on it a head start. The rotting wood becomes a sponge, holding water for the plants. Over time, this mound is not supposed to condense, as the wood rots, the roots from the plants on it will fill the voids.

“In the past, we have asked one thing of our gardens: that they be pretty. Now they have to support life, sequester carbon, feed pollinators and manage water,” wrote Douglas Tallamy, author, and entomologist and ecologist at University of Delaware. Garden stewardship, with the goal of supporting the soil’s natural cycle, has become an important task.

I’m not suggesting you do all of this, however; I could not do it all on my suburban lot. But using one or more of these ideas can make all the difference in your garden. Then you can share them with your neighbors, and slowly we can move towards more thoughtful and ecologically sound gardening. I’m seeing it in my neighborhood, in my design practice, and in small community gardens everywhere. Let’s keep the movement going!