Waste Management's New Facility In Elizabeth Turns Food Waste Into Energy.

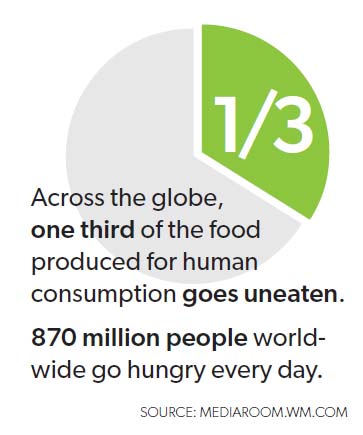

IN THE U.S. ALONE, MORE THAN 52 MILLION TONS OF FOOD ENDS ITS JOURNEY IN A LANDFILL EACH YEAR.

IN THE U.S. ALONE, MORE THAN 52 MILLION TONS OF FOOD ENDS ITS JOURNEY IN A LANDFILL EACH YEAR.

That’s more than a waste of food. Deprived of oxygen, a single head of romaine can take up to 25 years to decompose, producing climate-warming methane in the process. Yet, with recent innovations, that food may be put to productive use—even if it’s not on the plate. In the shadow of Newark airport, a new chapter in the state’s food-waste recycling history is being written at Waste Management’s CORe Organics Recycling Facility in Elizabeth, which opened in March of 2018. There, discarded organics are being transformed into green energy.

The proprietary CORe process transforms industrial food waste, from coffee grounds to green beans, into a potent engineered bio-slurry dubbed EBS®. As part of a public-private partnership, the slurry is transported to the Rahway Valley Sewerage Authority (RVSA) wastewater-treatment facility. There, it is added to their in-house waste digester tanks. Like an all-natural accelerator, it supercharges the breakdown of solids.

The resulting co-digestion produces a material identical to natural gas, which in turn powers the station’s generators.

Finding use in discarded food

Drawing on a model Waste Management developed at sister sites in three states, the program demonstrates an emerging pattern of partnership between waste producers, managers and municipalities that creates new value from trash. This is notable at a time when waste disposal rates are rising and landfill diversion is becoming a state and municipal priority—and the benefits go beyond economics.

Through this process, even food that is discarded for good reasons can be transformed into energy. As the romaine scares of late 2018 and 2019 unfolded, eaters rightly focused on the health risks. Unsurprisingly, there was a corresponding spike in leafy green food waste as supermarkets and distributors raced to remove product from their shelves.

During a tour of Waste Management’s CORe Centralized Organics Recycling Facility in December 2018, then CORe manager Scott Lewis (now the area public sector manager for the Greater Mid-Atlantic) outlined the event’s scale. “We have gotten trailer after trailer after trailer of romaine,” he said to a tour group from ANJR, the Association of New Jersey Recyclers.

He gestured toward the intake dock. “They just keep coming, and we just keep processing.”

There was a silver lining for those particular romaine heads: rather than heading into the landfill, they were taken out of the food system and given new life as green energy.

Finding value in what’s left behind

The first step in the CORe equation is to source the feedstocks for the engineered bio-slurry. When the New Jersey facility opened, meal-kit delivery service HelloFresh, which has a large distribution facility in Newark, was one of its first customers.

“Part of our branding is around minimizing food waste,” explains HelloFresh’s associate director of sustainability, Jeff Yorzyk. By tracking their supply chain closely and only providing what customers need for a recipe, meal kit companies ensure that the remains of a cilantro bunch aren’t discarded when home cooks need only two tablespoons for Taco Tuesday.

“Unsold inventory is usually a very, very small percentage of our total purchasing, and we have a very strong donation stream,” Yorzyk says, to the tune of 2.5 million meals a year. (Locally, the company has an ongoing relationship with Table to Table, a nonprofit in Englewood Cliffs that rescues food from donors and offers same-day deliveries to charitable organizations. In 2019, they also donated 3,000 sides from their Thanksgiving Box to the City of Newark for Thanksgiving.)

Yet, even with a tech-enabled supply chain and due diligence, some amount of food waste is a reality in a subscription-based business. From time to time, the company has some inedible material that can’t be donated. When it came online, the CORe facility offered HelloFresh an easy, superior alternative to sending unused ingredients to the landfill.

“I might have been one of the most excited people they have seen in there,” Yorzyk recounts of his CORe visit shortly after it opened. “I ran all around that whole process. I looked in all of the little windows to see that disgusting slurry of spoiled food. When you really start to get that there’s 98% plastic film coming out of one end of this process and then all of the organics are going out the other end into those big tanks, it’s fascinating. CORe is what you might call an elegant solution, where it saves us money, it does the right thing with the food and it’s going off and creating energy.”

That sentiment echoes a growing desire among food businesses to not just divert waste from landfills, but to achieve a greater environmental purpose, says John Hambrose, Waste Management’s communications manager—and New Jersey is at the leading edge of the technology curve. “Our Elizabeth facility is unique in that it is Waste Management’s newest CORe plant and incorporates everything we’ve learned about this technology and business at the three previously built plants in Los Angeles, Brooklyn and Boston.”

Digesting previously untapped potential

The CORe process kicks off on the tipping floor, where source-separated organics and palletized food waste from supermarkets, food distribution centers and a local prison are combined into teeming heaps that put the American food-waste issue into fast perspective.

First, food is separated from its packaging. “We actually tip the pallets in there, boxes and all,” Lenox said during the tour, pointing toward the tipping floor. “You can see some of the plastics, and this system will remove those residuals and just keep the food waste.”

A bucket loader churns giant piles of food to create a homogenous mix, which is loaded into a hopper and dropped into a separator. There, a screw auger pushes the mix up, and gravity drops it into a chamber where a 2.5-foot hammer mill loaded with blunt, rounded and sharp hammers pulverizes it with a meditative pulse. The mill is surrounded by a cylindrical screen that pulls the slurry outward centrifugally as it is ground down. Nearby, a compactor collects residual liquid, which is reloaded into the system, along with all the water used to clean the plant.

Odor-control systems turn the air over six times per hour, rendering it surprisingly benign.

The system is designed to create a thick slurry comprised of about 15–16% total solids, accounting for 90–94% of the incoming food waste. (Food waste contains 75–80% water by weight.) All told, the process takes about four hours, the machine whirring, grinding and pounding like a hungry mechanical beast.

Transferred to the tank room, the slurry settles for a day and is churned with a device like a boat propeller to achieve the desired consistency and allow for the expansion inherent to such an active material, rich with bacteria. (Essentially, it ferments.) The end result is an energy-rich material, which is delivered to the RVSA waste water-treatment facility 7 miles away in 6,000-gallon loads four to five times daily.

“It almost acts as a steroid for their digestion,” Lenox explains. “They are already digesting waste water and then they input a bit of our slurry into their digestor along with the waste water. The gas production increases like crazy.”

RVSA’s John Buonocore offers a simple metaphor for the next-stage process that takes place in the digestors at their plant: “The tanks function the same as a human stomach. It’s a steel container, there’s no oxygen inside and it digests the sludge and stabilizes it. The gas that comes off of the co-digestion is chemically the same as natural gas that you get in your stove.”

Currently, enough biogas is produced to supply 50% of RVSA’s power needs. Yet the vision goes even further, explains RVSA executive director James Meehan: “We’d like to someday become net zero with our energy.” If all goes as planned, they estimate that the plant—which processes roughly 30 million gallons daily from 250,000 New Jersey residents and 3,500 industrial and commercial customers— will become energy self-sufficient over the next several years.

There is also potential beyond the plant. The RVSA is exploring options to significantly increase its digestion capacity, allowing it to increase the amount of food waste processed, Buonocore says. “This will dramatically increase our gas production and allow us to explore additional ways to utilize our digester gas beyond just our Cogeneration Facility.”

Gathering momentum

According to Hambrose, the CORe plant has been processing about 100 tons of food waste per day over its first year, from lettuce to expired pizza dough. Existing permits allow them to scale to 500 tons, and he sees plenty of untapped potential among smaller waste generators, from restaurants to hospital cafeterias. “As the availability and benefits of this technology become more widely known in the market, we believe waste haulers, including Waste Management, will begin offering food waste collection services to smaller generators looking for a greener option for their food waste.”

There’s reason to root for that growth curve.

“Every ton of food waste recycled through CORe and co-digestion results in negative greenhouse gas emission of approximately 330 pounds of carbon dioxide,” Hambrose says— noting that the numbers account for energy used to transport waste to the facility, process it and deliver the EBS product to RVSA. “The energy created is renewable natural gas, a ‘green source’ [that] displaces energy derived from fossil fuels.”

That’s something that should turn the heads of municipal service providers, Meehan notes. “Any waste water treatment plant that has digestion capabilities and extra capacity should be doing this. Food waste does not belong in a landfill. It belongs in infrastructure that’s already bought and paid for by the public. It benefits the rate payer, and it benefits the environment.”

He estimates that the project could result in more than $6-million in rate-offsetting revenue over its first ten years. “That’s very conservative. We think it could do much better than that.”

NEW RESEARCH EXAMINES MEAL KITS & SUSTAINABILITY

Research from the University of Michigan published in 2019 sheds new light on the sustainability of meal kits, which have been criticized for contributing to packaging waste. In the first study of its kind, the process of getting food to consumers was examined, comparing grocery and meal-kit models side-by-side across five common meals, including salmon and cheeseburgers.

The result? An identical dish crafted from a meal kit rather than a grocery store was found to contribute one-third fewer greenhouse gases overall when every step was considered, from agricultural production through waste creation. This was largely attributed to streamlined logistics and pre-portioned ingredients. With meal kits reaching $3.1 billion in sales and growing, it’s food for thought. See: news.umich.edu/those-home-delivered-meal-kits-are-greener-than-you-thought-new-study-concludes/ to learn more.

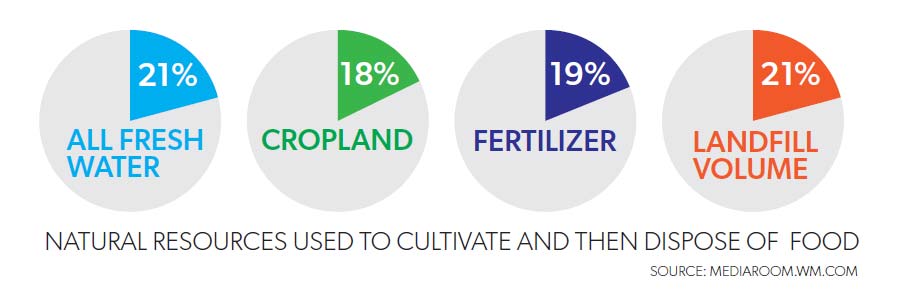

COST OF FOOD WASTE

More than 52 million tons of food are sent to landfills each year. The overall cost of this waste is an estimated $218 billion a year.