School Work in the Garden

Memories grown in a Waldorf school garden

Nine-year-olds wielding scythes working side by side in a wheat field. Third-graders harnessed eight at a time to a wooden plow, like oxen. Grade-schoolers making sachets of dried blood to ward off deer, and burying animal horns in the earth to feed the soil. These are some of the memories my daughters have of their time as students at the Waldorf School of Princeton.

My daughters are now in their 30s, and since their school days the number and popularity of school gardens have exploded. The National Farm to School Network reports that 40,000 schools in the United States now have a school garden, where they facilitate learning everything from basic math skills to nutrition. Without question, the gardening program at the Waldorf School of Princeton—and, indeed, at Waldorf schools worldwide—is one of the most intensive, and I’m grateful my children got to participate in it.

If my daughters and their classmates are any example, lessons learned in a school garden can create a lasting impression. My daughter Alice still can’t shake the experience of making those god-awful-smelling little sachets to tie onto the fence to keep deer out of the garden. Her sister Elizabeth was convinced, as a third-grader, that she was involved in witchcraft. “We concocted a biodynamic potion, stuffed it into some type of animal horn and buried it underground,” Elizabeth says. “After a moon cycle we took it out and used it to fertilize something.” (Not only have such biodynamic processes gained wider acceptance in recent years, especially in wine grape viticulture, but scientific studies have also found that biodynamic agriculture results in less-stressed soils and marked improvements in diversity of soil microflora and fauna.) It’s quite possible that Elizabeth’s concern about the dark arts may have been further aroused when later the class made their own brooms after cutting down broom corn from the school garden.

The most memorable gardening activity for my children, however, concerned the third-grade unit on farming. Almost all Waldorf schools—even the Rudolf Steiner School on Manhattan’s East Side— send their third-graders away to work on a farm for a week, and the Princeton school is no exception. But having their own sprawling campus on what was historically farmland allows Princeton’s students to dig deeper, literally. As in plowing fields.

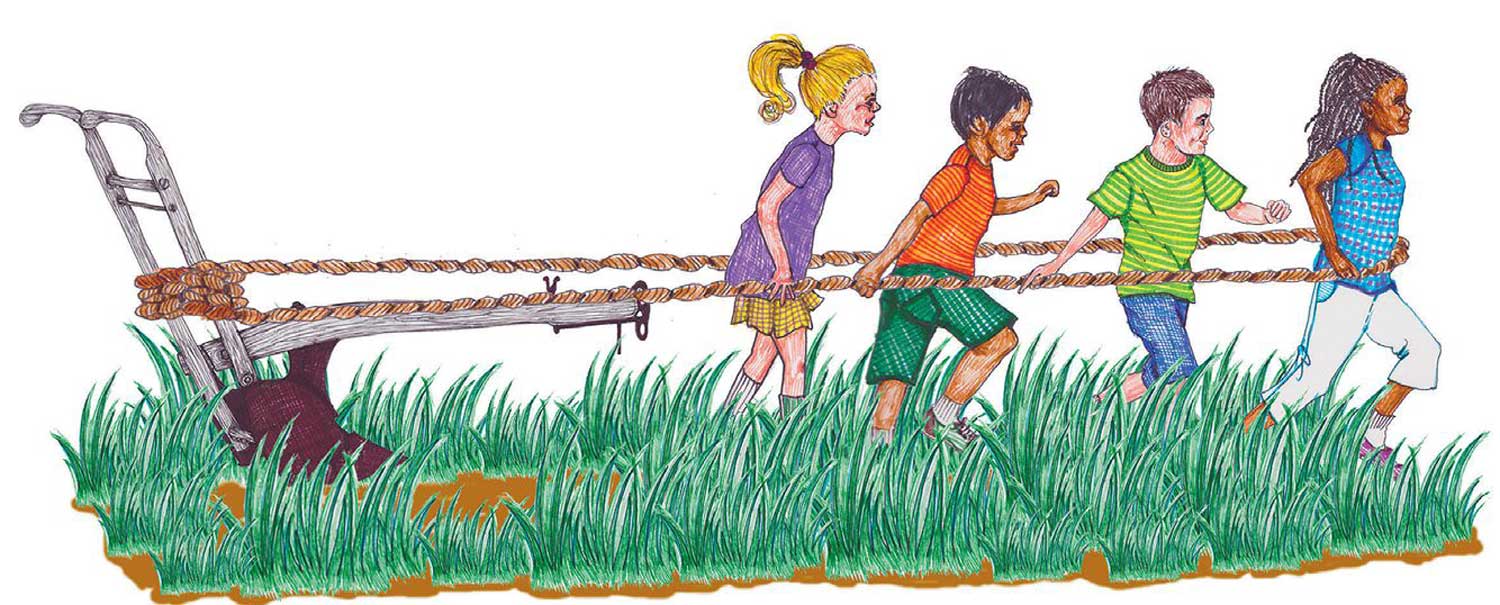

Elizabeth and classmate Ryan Lemmo both have strong if differing memories of working like horses (or oxen) to pull an antique wooden plow. “Our task was to till this patch of earth to plant potatoes,” Lemmo recalls. “This plow was massive, and there were ropes— straps? harnesses?— for maybe eight students at a time. We couldn’t believe that we were expected to pull this huge piece of equipment. I remember there being some tears and lots of resentment.”

Lemmo fears that relating his story may serve to “confirm all the odd stereotypes people have about what goes on in Waldorf schools.” But Elizabeth lists plowing among her favorite memories. It was not the multi-person plow she recalls, but a single-puller version. “I enjoyed strapping it to my back and plowing a plot like a horse. We all had to do one row, but I did multiple because I thought it was awesome,” she says. And the hard work spurred at least two alumni of the Princeton school to eventually establish farms at their colleges: Elisabeth Wolfe at Smith College in Northampton, MA, and Tobin Porter-Brown at Amherst College in Hampshire, MA.

Some activities have evolved at the Waldorf School since my daughters were students. The scythes have been replaced by push mowers and pruners, perhaps in the interest of modern safety, and biodynamic preparations using real animal blood and real animal horns have been replaced by herbal stirs. But the students still do get hitched to the plow like oxen.

To this day Elizabeth, a notoriously picky eater as a child, credits her love of asparagus to the Waldorf School’s huge stand. “In the fifth grade it was our job to harvest and cut back the plants,” she recalls. “I thought it was so cool that it was specifically our job to take care of them that I just kind of decided I liked eating them.”

Suzanne Cunningham, 32, has been teaching Waldorf students and cultivating the school’s one-acre biodynamic garden since 2009. She says the development of Elizabeth’s fondness for asparagus after working hands-on with the vegetable is a common experience. A similar story was related to her by a parent last year: “At the time, I was teaching the seventh-graders how to eat asparagus raw—it tastes like spring peas—and how to cook it,” Cunningham says. “The parent of a student named Camden said that Camden was in turn showing his younger sister the same thing. Now she will eat asparagus only if Camden prepares it.” And the phenomenon is not exclusive to asparagus. “It’s the same with the sautéed kale we make here,” Cunningham says. “Most people think it’s bland and for adult tastes only. Here, fifthgraders are fighting over the crispiest bits.”

Yet, says Jamie Quirk, the Waldorf School of Princeton’s communications and marketing director, getting little ones to eat their veggies is a side benefit, not the thrust of the program. “If our garden happens to produce a superior string bean, so be it,” she says. “But the biggest difference here is that the garden is viewed as an integral piece to the school, not an add-on. It’s an outdoor classroom, community gathering spot and so much more.”

The compost pile, for example, is a beloved campus fixture. When Alice Waters visited the Princeton Waldorf School back in 1997 (Waters is a Jersey girl who grew up in Chatham) she asked the sixth-graders who were leading her around the Waldorf garden, “Do you have a compost heap?” The students proudly showed her that they had not one, but three.

“The students love the compost pile because, in their words, ‘It’s so gross!’” Cunningham says, laughing. “And yes, they are amazed a year later that the compost has transformed into rich soil.”

Those compost piles made an impression on my daughters, too. “I remember being shocked that the compost pile was basically alive, and was a little scared of it because I was afraid of getting burned by the heat it generated,” Elizabeth says.

These days the Waldorf School garden boasts no fewer than four compost piles, which sit in front of a stand of Osage orange trees with fruit Cunningham hopes to use for a lesson on natural wool dyeing, along with tansy, a yellow-flowering herb from the herb garden. Leading me on her own tour of the school’s green acre, she points out two raised flowerbeds built by a previous eighth-grade class for the area where Waldorf preschoolers play, and a stand of towering sunflowers, which are the responsibility of the kindergartners.

Many of Cunningham’s lessons for the grade-schoolers take place in her outdoor classroom, a large tent with open sides that’s equipped with a movable blackboard. “Here I do garden and farm vocabulary with them.” She points to a lush, productive vegetable bed on the side of the garden that abuts the organic farm next door. “The land there was very low and flooded regularly. So I and the eighth-graders worked out a plan to deal with it—why it flooded, how to ameliorate it—and here it is.”

A large geodesic dome is used as both a greenhouse and an indoor classroom in frosty weather. “It’s where we start the seeds, in trays, in January and February,” Cunningham explains. “The kindergartners are the best students for planting seeds. This past year they started as much as two-thirds of our seedlings. Unlike eighthgraders, who just sprinkle them around, the kindergartners are so intentional, so careful. And they want to come back to see them growing.” Waldorf child development pedagogy connects this phenomenon directly to where sixyear- olds are in their physical, emotional and intellectual development. Says Jamie Quirk, “The kindergartners are tiny, undeveloped and need to be handled gently and with care—just like the seedlings.”

In the middle of this one-acre space there is now the Sitting Garden, a place for quiet reflection that was designed and built by the eighth-grade class that included my daughter Elizabeth and Ryan Lemmo. “Planning, planting and building our garden was particularly memorable,” Lemmo says. “It was broken into four different planted areas, with a path to a sitting area in the middle and a birdbath on one edge. I remember really needing to work together as a class to get it all done, which was difficult. But I found it so satisfying.

“When we graduated it wasn’t fully grown in and was a bit underwhelming. But it became one of the spots I always return to when I visit the Waldorf campus. Over the years, the plants continue to change, but it’s so nice to have that garden I worked on always there as a reminder.”

And The Winner Is...

Congratulations to the Princeton Day School, winner of the 2015 School Garden of the Year Award, for the best overall school garden, out of nearly 200 applicants. The award was presented by Edible Jersey magazine and the New Jersey Farm to School Network, with additional judges from the New Jersey Department of Agriculture, Rutgers Cooperative Extension Master Gardeners, the New Jersey Agricultural Society and the Alliance for New Jersey Environmental Education. The contest, held every two years, will return in 2017.

There’s at least one strong connection between the two excellent school gardens featured on this page: Years ago, Pam Flory, now garden coordinator at the Princeton Day School, was the gardening teacher who taught Pat Tanner’s daughters those memorable lessons at the Waldorf School of Princeton.