Michael Clifford is On a Quest to Preserve and Share the Flavors of New Jersey’s Apple Past

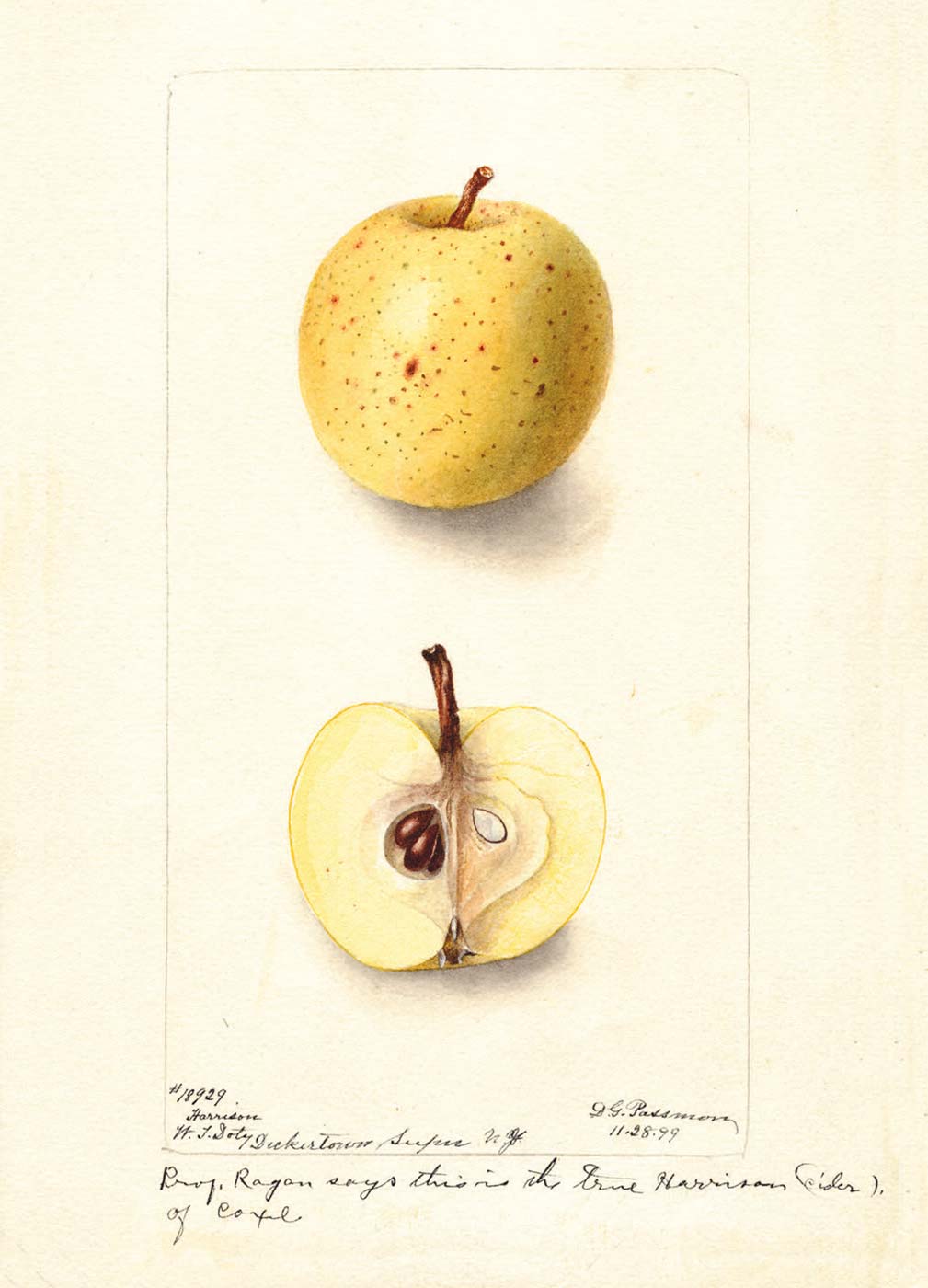

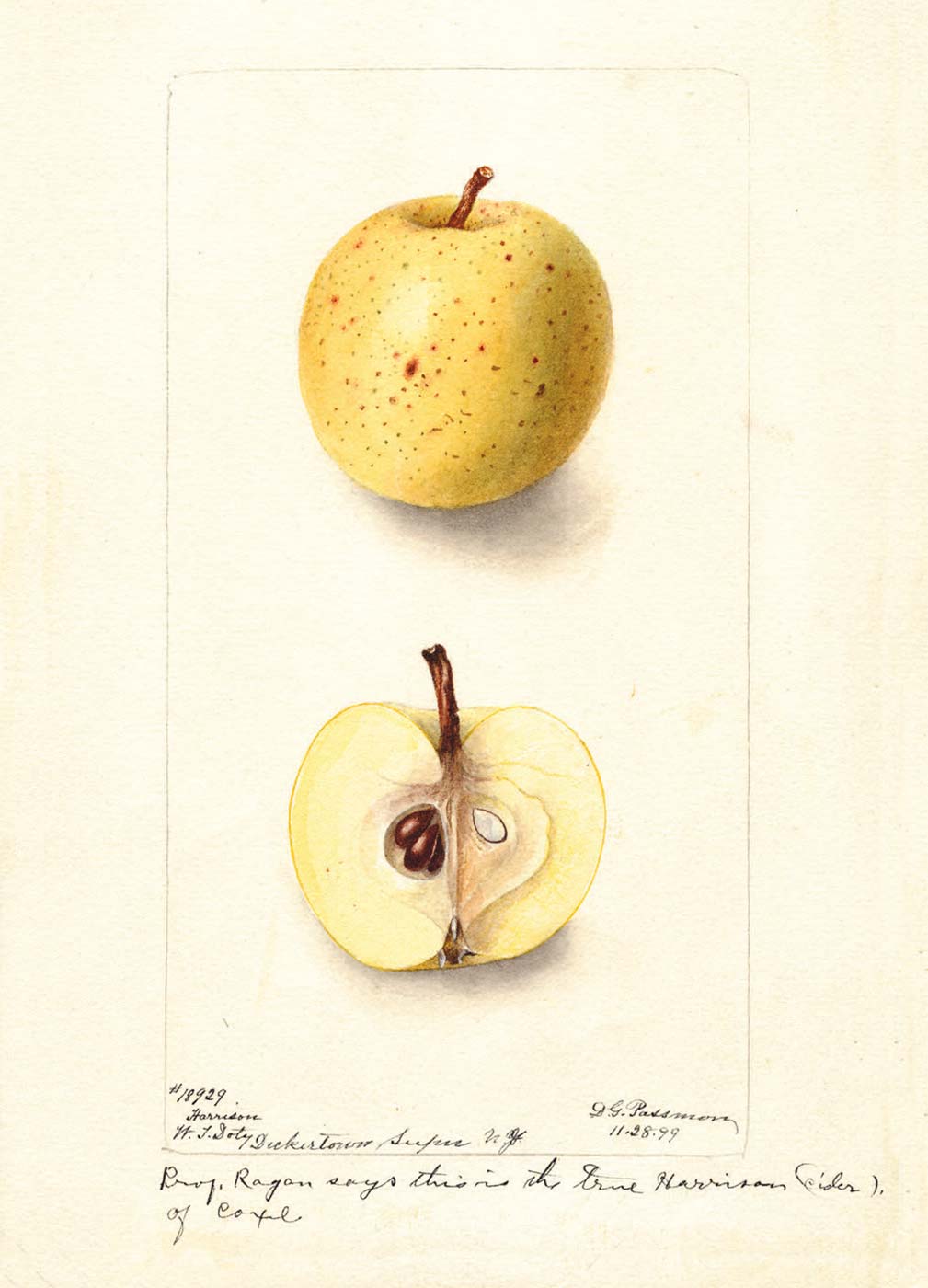

In 1886, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) undertook an ambitious project: the creation of a national register of historic and newly developed fruits. Over the next 56 years, a team of artists created 7,497 watercolor paintings that captured, in exquisite detail, images of America’s principal commercial fruit crops, including 3,800 paintings of cultivated varieties (cultivars) of apples. These paintings were part of a widespread effort to standardize the naming of fruits by giving American orchardists a centralized reference—and common understanding— of the physical qualities that defined specific apple cultivars.

Those paintings have also proven to be an invaluable resource for 21st century fruit explorers, such as Michael Clifford—a New Jersey–based apple explorer who hopes to find long-forgotten local apple varieties that were once enjoyed in our state’s homestead kitchens and roadside taverns. As Clifford drives along New Jersey’s back roads and suburban streets, he’s always on the lookout for aged dwellings and other signs of human settlement that alert him to the possible presence of old, neglected apple trees. But it was written clues at the bottom an 1899 USDA watercolor that led him to discover the oldest known surviving examples of one of New Jersey’s most renowned colonial-era apples.

Clifford caught the fruit explorer bug several years ago while living in Washington state, where he regularly encountered abandoned fruit trees when hiking. In June 2019, he reached out to David Benscoter, founder of the Lost Apple Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rediscovering lost apples in the Pacific Northwest.

“I did so much hiking, trekking, and bushwhacking through desert, prairie, and forested sections of the state and I would routinely come across 19th century homesteads with old apple and pear trees on them,” Clifford says. “I reached out to David to see if there was some way that I could help with identifying the location of old orchards and then get apple IDs on some of these abandoned trees.”

As part of the search process, Clifford scoured aerial survey photographs taken of Washington in the 1950s, looking for grids of dots that would indicate an orchard. Because these aerial surveys were taken across the entire United States, he was also able to examine aerial photos of the neighborhood around his childhood home near Morristown, and he discovered that there had been extensive apple orchards in that area in the mid- 20th century. When COVID hit and his employer, Microsoft, required employees to work remotely, he returned to New Jersey and began using his non-work hours to search for lost apple trees here. After one week of driving around Morris and Hunterdon counties, however, Clifford was overwhelmed by the sheer number of apples trees that he was finding. Realizing that he needed to refine his search, he decided to focus on finding trees that were at least 100 years old. That goal led him to rely on a combination of community outreach, historic research, and chance sightings of old trees.

Old, unpruned apple trees have a distinctive shape and scraggly growth with lots of vertical suckers. Having looked at many old apple trees, Clifford was able to instantly recognize them out of the corner of his eye as he drove through northern New Jersey on his way to go hiking or camping. If a tree looked sufficiently old, he’d mark the GPS coordinates and then check the aerial photographs when he returned home to confirm that the tree had been part of a mature orchard by 1930, the first year that complete aerial surveys of New Jersey were made. His reasoning was that trees already mature by that time had a greater chance of being a lost or rare variety than those planted at a later date.

The USDA watercolors also provided ideas for areas of the state to search. Because farmers from across the U.S. supplied the fruit samples that were painted by the USDA artists, the name of the person who submitted the fruit and the location of each point of submission is noted on the bottom of most watercolors. This enabled Clifford to use the searchable metadata on the USDA’s website to find which apples had been submitted by New Jersey farmers. As Clifford has a particular interest in old cider apples, one painting stood out to him: an 1899 painting of a Harrison apple, one of New Jersey’s most famous cider apples. The apple in that painting had been collected in Deckertown, Sussex County, by William Thomas Doty, a newspaperman and former editor of the Orange County Farmer in Port Jervis.

To narrow his Sussex County search, Clifford posted queries to several county and town Facebook groups, beginning with Wantage Township where Deckertown (now Sussex) is located. “I figured that was the most likely place I was going to find Harrisons,” Clifford says. “I just asked people if they had old, abandoned apple trees on their farms. A lot of people responded. Most people overestimated how old their trees were, but some people did have trees from the mid-19th century.” Remnants of several old orchard grids were also uncovered by searching the area using satellite images on Google Maps. In August, as he drove through Sussex County to look at trees, Clifford found the remnants of a very old orchard in Wantage that particularly excited him.

REALIZING THAT HE NEEDED TO REFINE HIS SEARCH, HE DECIDED TO FOCUS ON FINDING TREES THAT WERE AT LEAST 100 YEARS OLD.

Grafting a Legacy

When Lost Apple Project researchers identify a tree of interest, they return when the tree is fruiting, collect the fruit, and then send it off to experts in historic apples in hopes that they can identify the apple. Because many old apple trees in New Jersey no longer bear fruit—or, because of disease, produce misshapen, miscolored apples that are difficult to identify—Clifford decided on a different approach. He would graft scionwood onto dwarf rootstock (see sidebar) and then plant them in a nursery orchard. With proper care, these trees will begin to bear fruit in two to three years. He’ll then be able to remove any of those nursery trees producing apples that are still commonly available today and focus on identifying the remaining unknown apples.

That approach requires the arduous process of tracking down landowners and gaining permission to access their property to cut scionwood for grafting. “By fall 2020, I had marked about 200 trees in New Jersey alone, and I started writing letters. A lot of these were orchards with 15 trees so it wasn’t as bad as it sounds,” Clifford says. “Everyone that I wrote to responded—all except maybe one or two people—and they all gave me permission.”

In exchange for cutting scionwood, Clifford makes backup grafts that he will return to the landowners once the trees are strong enough to plant. He finds that most landowners are very excited by the idea that a tree on their land might be a lost apple. Sometimes, however, the act of cutting wood can be stressful. “I have had people come out just short of pointing a shotgun in my face, wanting to know what I was doing on their neighbor’s property,” Clifford says. “But once they realize I am there to cut applewood, they get very friendly very fast. It is difficult because I was just shaking and now they are, like, ‘Tell me more about your project!’ and I’m, like, ‘I need a beer first.’”

Ancient Cultivars Meet Modern Technology

In March 2021, permission in hand, Clifford returned to the old orchard in Wantage that had piqued his interest on his August 2020 drive. After cutting scionwood from each of the trees, he ran into the 94-year-old farmer-landowner, who told Clifford that those apple trees had been old when he was a child and that it hadn’t been a commercial orchard in his or his father’s lifetime. Based on that information and on their size (the trunks were almost 10 feet in circumference), Clifford calculated that the trees are perhaps 150 to 200 years old. When Clifford asked if he knew what variety of apples were growing there, the farmer responded “It’s a bunch of Canfields. I don’t know what those are, but that’s what my dad called them. And the rest of the trees are a small yellow apple that I never knew the name of.” This was exciting news to Clifford, as the Canfield, an 18th century cider apple that originated in Newark, was often planted with the Harrison, a small yellow apple. Together, the two varieties were a traditional combination in cidermaking.

In his 1817 book A View to the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, William Coxe provided the first comprehensive catalog of American apple cultivars. Coxe wrote that on the Harrison apple “the skin is yellow, with many small but distinct black dots… the taste pleasant and sprightly.” The Canfield, he writes, is “smooth and red… the flesh white, firm, sweet and rich.” And he confirms that the two apples were usually mixed in equal portions to make cider and that the cider from each commanded a price premium.

When Clifford picked apples in the Wantage orchard the following fall, he found that they matched Coxe’s descriptions of the physical and flavor characteristics of the Canfield and Harrison. For further verification, Clifford sent leaf samples to Cameron Peace, professor of tree fruit genetics at Washington State University, to have DNA samples run.

Peace, together with collaborators around the world, has assembled an electronic dataset containing the DNA profiles of several thousand apple varieties. New apple tree samples submitted to his lab get DNA-profiled and compared to the dataset to try to determine their identity and parentage. Each new profile then gets included in the growing dataset for Peace and others to compare to future samples. They are trying to build a single family tree of all apple varieties, given the many close pedigree relationships among cultivars that are being uncovered.

In February 2022, Clifford received the test results. The Canfield was an identical genetic match, but the suspected “Harrison” was a total mystery. It did not match the Harrison in the database, and, Peace informed him in an email, “There is no parent-child relationship either. In fact, your sample is not close to anything. Nothing [in the database] even seems to be a grandparent.” He did note that both the Wantage tree and the Harrison in his database are descended from the Reinette Franche, a 16th century French cultivar—but, he wrote, so are most American apple varieties.

Chasing Every Clue

With the tenacity and curiosity of a true apple explorer, Clifford is more intrigued than discouraged by the news that the yellow apple’s origin is a mystery. He sees two paths before him: Try to prove that this is, in fact, the authentic Harrison, or, failing that, try to discover what cultivar it is. He is spurred along the first path by a note that appears at the bottom of the USDA painting, which reads “Prof. Ragan says this is the true Harrison (cider) of Coxe.” “Prof. Ragan” refers to William Henry Ragan who, as part of the USDA’s effort to standardize and shorten apple names, compiled a comprehensive list of apple cultivars and their synonyms (17,000 in total), which was published in 1905 under the title Nomenclature of the Apple; a catalogue of the known varieties referred to in American publications from 1804 to 1904. This note on the watercolor indicates that there were multiple apples in circulation in 1899 that were given the name Harrison, reflecting two concerns the USDA was addressing at that time: fraud in the apple industry and the lack of standardized naming.

To prove his theory that this is the true Harrison, Clifford is likely in for a long search filled with tantalizing clues and frustrating dead ends, exactly the sort of detective work that draws people into the search for lost apples (see sidebar). The tree that yields this small yellow apple is placed very clearly within an orchard grid, so one can rule out the idea that it is an unnamed seedling tree. “The tree matched what I had read about the Harrison in Coxe’s book,” Clifford says. “And when I pressed the apple, the resulting cider had the same color that he described, which is a deep, deep amber.” But, the Harrison DNA profile in Peace’s database comes from an apple tree that was identified as a Harrison by someone who had direct knowledge of its origin—a man whose grandfather had planted that tree and had told his family that it was a Harrison. And, in 2021, the Wantage yellow apples fell from the tree in September, rather than early November as Coxe described—leaving Clifford to investigate whether that year was an anomaly, if apples are ripening earlier than they did 200 years ago, or if that early ripening date will ultimately disqualify it as a Harrison.

A Legacy At Risk

In addition to the Harrison, Clifford is in pursuit of several other apples. His list includes the Tewksbury Blush, which originated in Hunterdon County, and Victuals and Drink, an 18th century Newark apple, to name a few. The search is made more urgent by the annual loss of old trees.

“Some seasons are worse than others when it comes to disease,” Clifford says. “When I first started doing this in 2020, a lot of the trees that I intended to come back to in the winter to cut scionwood from had died by the time winter rolled around. Or they had been cut down by farmers because they were so diseased that they assumed they weren’t worth rescuing.”

Once he finds trees in his nursery that produce promising fruit, even if the variety is currently unidentified, Clifford will graft more trees for the orchard he is planting on land he recently acquired in Long Valley. From there, he will get as much scionwood out to other growers as possible on the belief that widespread commercial adoption of an apple will be the key to keeping those apple genetics around.

“If I find an apple that I’m excited about, I want to grow as much scionwood as I can and start mailing it to people,” Clifford says. “That’s the kind of recovery and preservation I’d like to see because you could put one or two of these trees in a preservation orchard, but COVID happens, they lay off staff or there are budget cuts so they can’t afford to maintain it for one year and then the next year the trees are gone.”

Because Clifford would prefer to return to the original trees to collect this additional scionwood, he worries that some of these ancient trees will not survive the two to three years he needs to wait until his nursery trees produce fruit. This identification process could be greatly speeded up by having DNA screenings of the leaf samples from 260 apple trees that Clifford currently has prepped for testing, but with a cost of $120 per test, the price tag is, for him, prohibitive. Peace has been trying to find a way to bring down the cost of testing and is also seeking grant funding to develop and provide a single repository of reliable cultivar information for U.S apples—a goal that echoes, and vastly expands upon, the USDA’s original watercolor efforts. As Peace adds more and more samples into this database, it raises the likelihood that another tree that matches the Wantage “Harrison” will be found, perhaps with a name and origin story attached.

THE CANFIELD, AN 18TH CENTURY CIDER APPLE THAT ORIGINATED IN NEWARK, WAS OFTEN PLANTED WITH THE HARRISON, A SMALL YELLOW APPLE. TOGETHER, THE TWO VARIETIES WERE A TRADITIONAL COMBINATION IN CIDERMAKING.

Connection to the Past

Along with the hope of rediscovering lost historic New Jersey apples, Clifford’s search is also driven by a desire to understand more about the people who planted these orchards and what drove their decisions to plant specific cultivars.

“I’ve always been really, really fascinated with local history, especially the portions that aren’t well documented,” Clifford says. “That gave me motivation to go out and do this, even when a lot of the people around me thought I was investing too much in this. Or trying too hard. Or,” he adds with a laugh, “becoming a little bit obsessed, which I have.”

One hundred fifty years ago, Americans had a much better understanding of the best way to use specific apple cultivars than we do today. They knew which ones had to be eaten fresh off the tree and which ones could hold up for months in the root cellar. And they had favorite varieties for making sauce, pies, molasses, and, of particular interest to Clifford, cider.

“When I started, I thought the value of all of this was to find good cooking, baking, and eating apples that had really interesting flavors that you couldn’t get in commonly available varieties,” he says. “And then my first apple ID was a cider apple and I realized that a lot of these apples in New Jersey are going to be cider varieties. I think that’s another area where these ‘extinct’ apples could have a real impact because there are a lot of people in cider who are doing really interesting things.”

At this moment, the Canfield trees in Wantage appear to be the oldest remaining specimens of that cultivar. When Clifford sent a few apples from those trees to John Bunker, an expert on Maine’s lost apple cultivars who has tasted thousands of apples, he remarked that the taste was unusual, distinctive, and unlike what he is used to—an indication that even among cultivars, such as the Canfield, that are already commercially available, Clifford’s New Jersey discoveries could have regional distinctions that add new flavor contributions to the craft cider world.

And if the Wantage “Harrison” remains unidentified? “I’m very interested to see what these apples will produce in terms of a cider. Discovering a lost apple is amazing, but discovering an amazing cider apple? That would be a real discovery,” Clifford says. “I would love to produce something that is really unique and captures part of the range of what people in the 18th and 19th centuries would have expected when they ordered cider.”

“At the end of the day,” he adds, echoing the timeless sentiment of apple lovers who value experience over name recognition, “if an apple makes good cider, it makes good cider.”

To follow updates on the search for lost apples, visit ediblejersey.com.

BECAUSE FARMERS FROM ACROSS THE U.S. SUPPLIED THE FRUIT SAMPLES THAT WERE PAINTED BY THE USDA ARTISTS, THE NAME OF THE PERSON WHO SUBMITTED THE FRUIT AND THE LOCATION OF EACH POINT OF SUBMISSION IS NOTED ON THE BOTTOM OF MOST WATERCOLORS

HOW TO BE AN APPLE HUNTER

Successful apple hunting requires a particular constellation of skills and attributes. John Bunker, author of Apples and the Lost Art of Detection (2019), breaks down the challenge into two categories: an apple with no name (lost identity), or a name with no apple (missing). Addressing either is a process of eliminating possible contenders. This requires patience, perseverance, good observation skills, disciplined recordkeeping, close attention to details, and a healthy dose of skepticism.

Specialized skills can be very helpful in the hunt for lost apples. In his work for the Lost Apple Project, founder David Benscoter relies on skills he acquired in his 24 years as a criminal investigator with the FBI and IRS. Michael Clifford, who holds a master’s degree in Medieval Studies, acquired useful research skills during the time he spent working as a junior archivist at Princeton University—and he has the advantage of growing up in the digital age.

“The time that I spent at Princeton was really helpful because it taught me how to work these databases and find things in a library,” Clifford says. “I grew up with Google Maps and I know about the ArcGIS system and all of that. The tech side of things was a huge advantage because, with so many of these old records being digitized, I would uncover things that I felt people didn’t know existed.”

When one finds an old apple tree, the first step is to determine whether it is a cultivar (a cultivated variety that’s reproduced by grafting) or a seeding (grown from seed). Look for a graft line along the trunk—a bulge or change in the color of the bark, often three to four feet from the ground. If you can’t find the graft line but you find two or more trees together that produce identical apples, those are grafted. And trees that are clearly part of an evenly spaced grid are most likely cultivars.

If you are lucky, the landowner will know the name of the cultivar, although you still need to verify that identity. If the name isn’t known, ask around among older residents and the local historical society—checking its archives for old diaries, photographs, and orchard lists and maps. If no one knows the apple’s name, you’ll have to start eliminating contenders.

Knowing the approximate age of the tree can help you eliminate any apple cultivars that were discovered or developed after the time period when the tree was planted. Check agricultural yearbooks, lists from local agricultural fairs, and nursery catalogs from that time to find out which apples were commonly planted in that area. Orchards were often planted in predictable combinations, so if you can identify other apples from nearby trees of the same age, that will help to narrow down the choices for an unidentified apple.

An apple tree planted outside the kitchen door of an old farmhouse, away from the main orchard, is likely a variety that ripens in the summer because those apples don’t usually keep well and were typically for home use. Examine the apples on the tree carefully because a farm family would get overwhelmed, or bored, trying to use up an entire tree’s worth of apples quickly, so, it was not uncommon to graft multiple summer apples onto a single tree.

Once you have your list of potential cultivar candidates and some sample apples from your tree, compare the taste, shape, color, ripening time, and tree characteristics against early images, such as the USDA watercolors (these have been digitized and are available on the USDA website*), and descriptions in books, such as A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees (1817), The Apples of New York (1905), and The Fruits and Fruit Trees of America (1886). Or get your hands on a copy of the seven-volume The Illustrated History of Apples in the United States and Canada (2016), in which Daniel Bussey has combined the USDA paintings with a compilation of historical descriptions and alternate names for 16,000 North American apples. And for an in-depth lesson in how to examine and describe the physical characteristics of an apple—plus a delightful collection of stories of apple explorations in Maine— a copy of Apples and the Art of Detection is a must-have. —FM

APPLE REPRODUCTION AND THE ORIGIN OF AMERICAN APPLES

Because they provided abundant fruit for fresh eating, cooking, drying, winter storage, and the making of vinegar and hard cider, apple orchards were a crucial component of colonial and early American homesteads and communities. Planting an apple tree from seed was an inexpensive way to get an orchard started, but each of those seedling trees produced apples that bore little or no resemblance to the apple from which that seed was taken. As a result, these early orchards yielded American apple varieties that were unique and new.

Most seedling apples are bitter, astringent, and only good for fermenting into hard cider. When apples from a seedling tree possessed desirable qualities, such as great flavor, additional genetically identical trees were then propagated using grafting—cutting a small branch with dormant buds (known as a scion) from the parent tree and inserting it into a matching cut on the limb or rootstock of another apple tree. The two are bound together, eventually growing together and producing apples that match those of the parent tree, with the rootstock determining the size of the resulting tree—from dwarf trees that are only a few feet tall to full-sized trees that reach 30 feet.

Scions from desirable trees were often passed along to other orchardists in the community. In this way, thousands of unique American apple cultivars were developed. Many of them never spread beyond the region in which they were first grown and most disappeared from production with the commercialization of the apple industry, which directed growers toward a limited selection of apples.

With these changes in the apple trade, once-beloved American apples disappeared from the marketplace. Yet, because apple trees can live for several hundred years, isolated trees still remain in abandoned fields, state forests, convent gardens, and suburban backyards— awaiting rediscovery by fruit explorers (arboreal archeologists) as they scour the countryside looking old trees.

AN UPDATE: Is It a Harrison? The Experts Weigh in on the Wantage Yellow Apple

In Fall 2022, Michael Clifford sent samples of the small yellow Wantage apple to three leading experts in historic American apples. Clifford asked them to weigh in on whether they believed the Wantage apple could be a Harrison. Their responses below reflect the caution, attention to detail, and patience that are the hallmarks of a good apple explorer.

John Bunker, a longtime Maine apple explorer, author of Apples and the Art of Detection (2019), and founder of Fedco Trees and the Maine Heritage Orchard, responded that, because of the tree’s advanced age and deteriorated condition, it is not possible for him to make an ID based on the physical characteristics of the apples he received. He suggested grafting new trees, which he offered to plant in his Maine orchard, and then, in a few years, assessing apples from these young, vigorous trees.

Paul Gidez, a self-described student of natural history, is the orchardist who is responsible for rediscovering the Harrison apple—locating a tree in Livingston (NJ) in 1976 that was identified as a Harrison by someone with direct knowledge of its origin. Gidez gave his first impressions upon tasting the yellow Wantage apple: “The flavor element here is unique to me, it’s pronounced, and it’s quite wonderful and special. It certainly is not a random wild apple, and it should be treated with respect.” At Gidez’s request, Clifford sent him photographs of the original tree and of leaves on a grafted stem in Clifford’s nursery orchard. In an email, Gidez responded: “Wow, I see why you thought these were Harrison. Visually very close! Yours has those russet streaks below the stems on the top of the apple; I don’t recall my Harrison showing that generally, but maybe some did. The first season grafted stem with leaves photo looks just like my Harrison. The whole tree photo differs from my Harrison.” Having raised Harrison apples since the late 1970s, culminating in an orchard of 250 Harrison trees, Gidez is deeply familiar with the characteristics of the Harrison apple. In a follow-up email to me, Gidez expressed his admiration for the way that Clifford is conducting his apple explorations, however, he also noted “His apple is definitely not the same as my Harrison and I believe not Coxe’s Harrison either.”

Paul Gidez, a self-described student of natural history, is the orchardist who is responsible for rediscovering the Harrison apple—locating a tree in Livingston (NJ) in 1976 that was identified as a Harrison by someone with direct knowledge of its origin. Gidez gave his first impressions upon tasting the yellow Wantage apple: “The flavor element here is unique to me, it’s pronounced, and it’s quite wonderful and special. It certainly is not a random wild apple, and it should be treated with respect.” At Gidez’s request, Clifford sent him photographs of the original tree and of leaves on a grafted stem in Clifford’s nursery orchard. In an email, Gidez responded: “Wow, I see why you thought these were Harrison. Visually very close! Yours has those russet streaks below the stems on the top of the apple; I don’t recall my Harrison showing that generally, but maybe some did. The first season grafted stem with leaves photo looks just like my Harrison. The whole tree photo differs from my Harrison.” Having raised Harrison apples since the late 1970s, culminating in an orchard of 250 Harrison trees, Gidez is deeply familiar with the characteristics of the Harrison apple. In a follow-up email to me, Gidez expressed his admiration for the way that Clifford is conducting his apple explorations, however, he also noted “His apple is definitely not the same as my Harrison and I believe not Coxe’s Harrison either.”

Dan Bussey, apple historian and author of the seven-volume The Illustrated History of Apples in the United States and Canada (2016), concurred, saying that, because of several reasons, including the shape of the apple and the early ripening date, he does not believe this is a Harrison. He is, however, extremely excited about the distinctive flavor and character of this apple. Calling it “a treasure,” he noted that it is too unique of an apple not to have been an important cider apple in its day. Bussey also has a theory as to the true identity of this apple. “There was so much character to this apple that I couldn't believe it to be a chance seedling,” Bussey wrote to me in an email. “I ran across my notes on the Forest Styre apple, and it seemed to fit many of the descriptors. It's a special apple in my mind and one that I hope may indeed be the long-lost Forest Styre.”