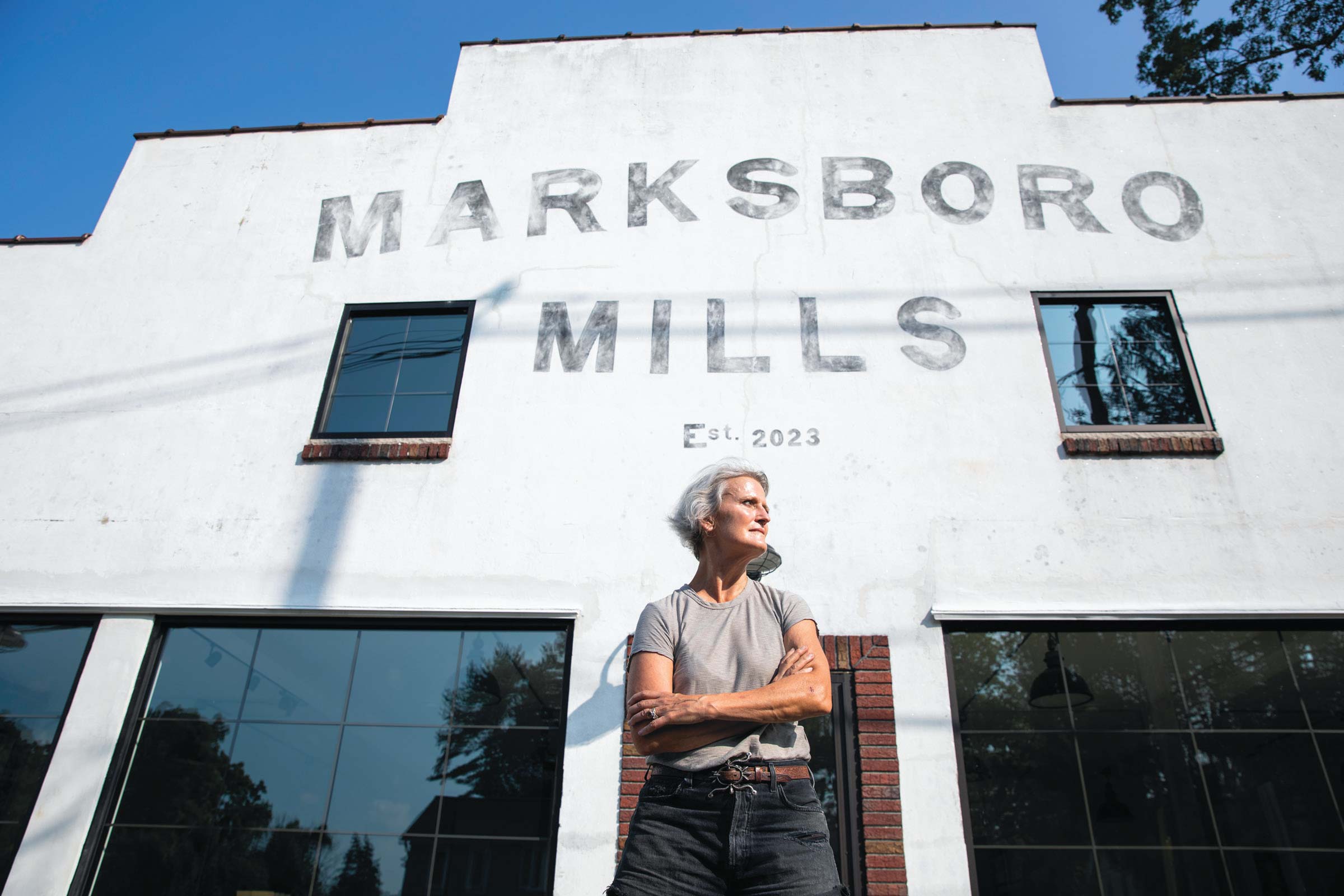

In Marksboro, Ruthie Perretti Brings New Attitudes to Ancient Ways of Growing, Milling, and Baking

In her 2021 Wall Street Journal article about the new grain mill that Ruthie Perretti was building in Warren County, reporter Leslie Brody explored the aspirations and challenges of reintroducing small-scale grain growing and milling to the region. Under the headline “A Pizzeria Owner Who Wants to Reinvent Local Farming—and Still Sling a Tasty Pie”, Brody examined Perretti’s desire to grow grains on her farm in Marksboro, a tiny hamlet in Frelinghuysen Township, and have them milled for use at Ruthie’s BBQ & Pizza, the now-shuttered Montclair restaurant she co-owned with her chef-husband, Eric Kaplan.

While the article was upbeat and hopeful, many of the readers’ comments were not. Dismissing her efforts—and those of advocates for organic and local food—as impractical and elitist, commenters focused on the single measure of yield-per-acre as proof of the superiority of commodity grain production. In doing so, they ignored the multiple, interconnected goals that animate the local grain movement, which focuses on the social, environmental, economic, and culinary benefits gained by reestablishing close ties among local farmers, millers, and bakers.

When Perretti’s parents purchased a 38-acre Marksboro farm in the 1970s, they created a country retreat where they entertained friends and Perretti’s mom reconnected with the wide-open landscape of her rural Midwestern youth.

“They both loved this area,” Perretti says. “They found this abandoned little pre-Revolutionary farmhouse that was in ruins. They ended up buying it, restoring it, and turned it into their weekend retreat. They loved it. And I loved it. It was just like a dream.”

The farm, now named Ruthie’s Farm, became the place where Perretti went to decompress from her professional life in New York City where she was senior vice president of design at Ralph Lauren and later owner of a branding consultancy that included Timberland, Newman’s Own, and Spike Lee among its clients. She eventually purchased the farm from her brothers in 2011. Throughout her family’s ownership, the local farmers who helped manage the land had primarily grown hay and other livestock feed. That changed in 2016 when Perretti took a more active role in the management of Ruthie’s BBQ and in the diversification of what was being grown on her farm—beginning by raising organic produce on a former hayfield.

With the remaining acres still in hay and feed grains, Kaplan posed an intriguing question: Could the couple raise their own wheat and mill it into flour for the pizza at Ruthie’s BBQ? The idea immediately appealed to Perretti. “It’s the very thing that my dad used to say to me back in the ’70s,” she says. “Dad and Mom used to travel to Europe a lot. They loved the food and would always say ‘Look at how the food changes from region to region; they’re just eating what they’ve got.’ Dad would come back to Marksboro and he’d say, ‘Ruthie, someday we should be growing food for fine restaurants in New York City.’ And I’m, like, ‘You’re exactly right!’”

EACH BAG OF FLOUR CARRIES THE NAME OF THE FARM FROM WHICH THE GRAIN WAS SOURCED.

RECENT CROPS INCLUDE OATS, AMARANTH, WINTER WHEAT, RYE, EINKORN WHEAT, AND BUCKWHEAT.

In Search of a Miller

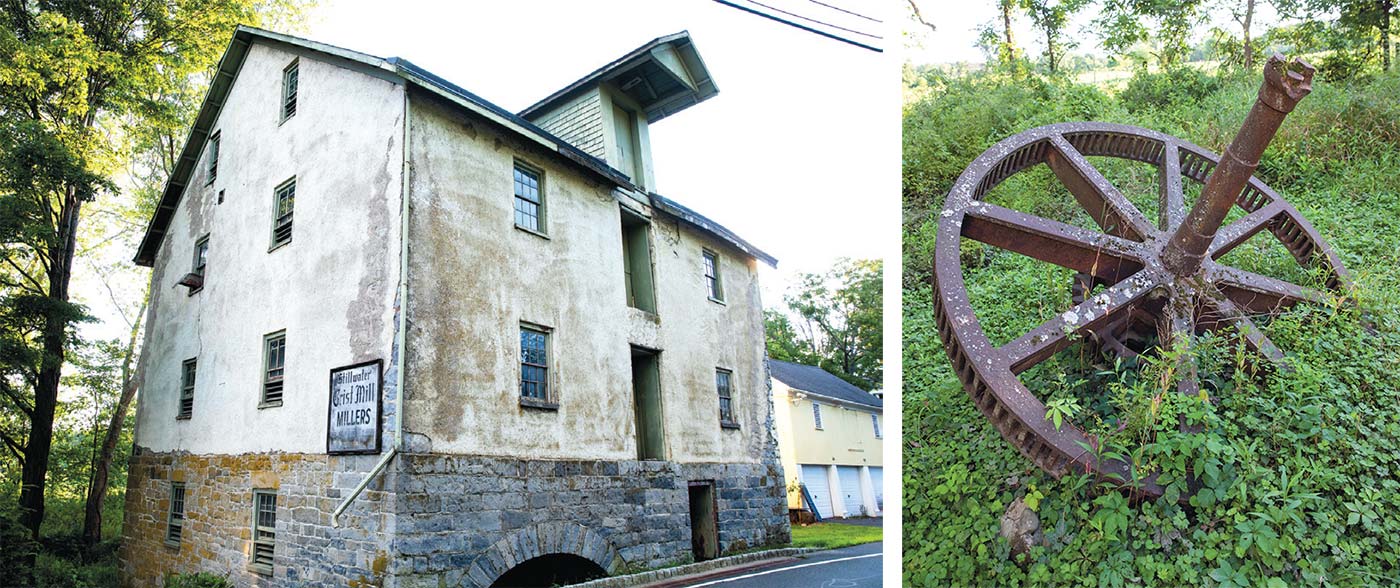

In response to Kaplan’s query, Perretti searched for local millers—a search that proved fruitless because this once-important piece of local processing infrastructure had long ago disappeared. The absence of mills in Marksboro was particularly poignant as the town was named for (and by) Colonel Mark Thompson, a prominent landholder who, around 1760, built a stone gristmill, which still stands along the Paulins Kill—the stream that forms one boundary of Ruthie’s Farm. According to Harry B. Weiss’ The Early Grist and Flouring Mills of New Jersey, Thompson’s mill was still in operation at the time of the book’s publication in 1956 and was, Weiss wrote, “one of the only in New Jersey at present where corn, wheat, oats, and barley are ground between millstones.”

Just as Perretti was giving up her search for a mill, she received a call from Sister Miriam MacGillis of nearby Genesis Farm.

“She reached out to me asking if I would like to grow grain organically. That there are some millers that are just starting out. I was completely intrigued.” The millers were Lenny Bussanich, Mike Hozer, and Larry Mahmarian, a trio of friends who, in 2016, formed River Valley Community Grains (see Edible Jersey, High Summer 2018), a local grain hub that assists growers in converting land into organic grain production for human consumption and then provides support services—cleaning, milling, packaging, and marketing—for that grain.

River Valley Community Grains grew out of a project at Genesis Farm that sought to restore and protect the Musconetcong River Valley. The trio recognized that encouraging and facilitating the use of regenerative farming practices within the Musconetcong watershed would be a major step toward protecting the health of the river. Grains were chosen because they were already being grown as livestock feed on many of these farms, so the farmers had essential farming experience and equipment. Of equal importance to Bussanich, Hozer, and Mahmarian was the return of fresh, nutritious, flavorful, heritage grains into the local food supply.

In 2017, after meeting with River Valley Community Grains, Perretti asked her farmer if he would be willing to convert some of her land to the growing of grains using organic practices. He agreed to try and they began consulting with Elizabeth Dyck, an agronomist who works closely with River Valley Community Grains.

“Elizabeth really helped a lot, because to transition over involves cover cropping and really understanding what kind of grain is going to do best in your conditions,” Perretti says. “She held our hands and directed us along the way. We started with winter wheat, a hard red variety, and it did incredibly well. And after that we grew oats and a couple different varieties of winter wheat—all with Elizabeth’s guidance.”

At the time, Bussanich, Hozer, and Mahmarian were still working full time at other jobs and milling one night a week in a commercial incubator kitchen in Long Valley. It soon became apparent to Perretti and the trio that commitment to the vision would require a permanent milling space located close to the farms it served.

“Pretty quickly I started thinking about infrastructure, because they had a temporary space they were working out of and they were very, very small at the time,” Perretti says. “And I thought, if we had a mill, we could really effect some change and really affect other growers in the area, because farmers would say to me, ‘I can grow anything. I just can’t bring it to market.’”

left, John Bennet, farmer, Ruthie’s Farm; right, Ruthie and chef/husband Eric Kaplan

Bringing a Vision to Life

That mill space ended up being right across the road from Ruthie’s Farm, in the former site of H.G. Rydell Farm Equipment where Harold “Cappy” Rydell once sold new and used farm machinery and parts.

“It was a much-loved place. He had every part for every farm equipment that you could imagine,” Perretti says. “People tell me stories of going in there and Cappy would be, like, ‘I know I got a piece for that. Just give me a couple days, I’ll find it.’ It was a real communal place for all the guys who were farming. Whenever I talk about this place, I’m going to be calling it Marksboro Mills. But to the locals, I always refer to it as Cappy’s.” Perretti purchased the property from Cappy’s sons in 2020 and, in April 2023, after renovation to the front building, River Valley Community Grains moved their equipment in and began to mill. (See related story, page 48.)

At present, the farmers supplying River Valley Community Grains have a combined total of about 50 acres planted in grains earmarked for the mill. Recent crops include oats, amaranth, winter wheat, rye, einkorn wheat, and buckwheat. This local supply is currently being supplemented with organic grain grown by farmers in Pennsylvania. Expanding local acreage in the coming years will require a delicate balancing of supply and demand in a way that allows for steady, managed growth. And the trio are very aware of the need to prove their marketing credibility to farmers who, at this stage, generally commit just a small portion of their land to grain for the mill.

On the farmer side, River Valley requires adherence to regenerative growing practices, which, for them, mirror the USDA organic protocols. A consultant to many organic grain growers in the Northeast, Dyck is an invaluable partner in River Valley’s efforts, providing guidance to farmers as they transition to growing grains without conventional pesticides.

“She’s very connected to the relationships and the conversations that we’re having locally about evaluating the land—the soil history, the management history, the testing of the soil samples, and essentially creating the plan and advising on what to do in preparation for accepting the grain,” Mahmarian says.

River Valley acquires and provides seed for their farmers, which ensures consistency in the crops being grown and transparency in their supply chain. Post harvest, they also manage the cleaning and storage of the grain. Each bag of flour carries the name of the farm from which the grain was sourced. And the farmers see a higher economic return than they do for commodity crops.

“The farmers get their benefit because of the value of these grains versus what they would traditionally farm,” Mahmarian says. “What we learned, as far as the relationships that we’ve built, is that there could be a two- to three-times [revenue] multiple on these grains versus corn and soy.”

That higher return is achieved through the hand selling and relationship building done by the River Valley team. Mahmarian now works full time for River Valley. So does Bussanich, although he also does contract consulting for the Northeast Grainshed Alliance—a membership organization made up of farmers, millers, maltsters, brewers, bakers, distillers, restaurateurs, and researchers working to increase the demand for, and supply of, grains grown in the Northeast.

Much of that hand selling takes place at farmers’ markets, where customers will find Bussanich or Mahmarian behind the table explaining the products, work, and mission of River Valley. In 2022, they were at 15 weekly markets, a strategic and physical challenge that paid off in increased sales and name recognition. At the markets they offer whole and milled grains, as well as co-branded products, such as granola, crackers, and other baked goods, made by local small-scale processors using River Valley oats and flours.

Farmers’ markets give River Valley the opportunity to tell their story directly to customers—and to get direct feedback on their products.

“People mention the earthiness and the nuttiness of the flavor,” Bussanich says. “We’re really not doing a lot of sifting, so we’re keeping the bran and the germ intact. That’s where all the flavor is and that’s where all the nutrition is. I think that’s coming out in the bread-baking process.” Perretti concurs, describing the flavor of fresh, whole local grains as “beautiful”—a flavor that she is confident many chefs and bakers will enthusiastically embrace.

Along with direct-to-consumer sales, River Valley services wholesale bakeries and retailers in New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia—some of which purchase cleaned whole grains and then mill their own flour in house. “Some days I do a lot of deliveries,” says Bussanich, who put 30,000 miles on his car last year. “I’ll usually start my day with making Jersey deliveries, like Montclair and Bloomfield, and then will travel into Brooklyn and Manhattan and then from Manhattan down to Philly.”

IT SOON BECAME APPARENT TO PERRETTI AND THE TRIO THAT COMMITMENT TO THE VISION WOULD REQUIRE A PERMANENT MILLING SPACE LOCATED CLOSE TO THE FARMS IT SERVED.

A Shared Mission

The tremendous personal investment of time and effort spent on marketing, deliveries, and working with farmers, as well as milling and packaging, is indicative of the growth-over-time, work-with-what-you-have, demonstrate-what-is-possible philosophy that has guided Bussanich, Hozer, and Mahmarian since the start of the company. It’s a perspective that immediately appealed to Perretti.

“I really liked their approach,” she says. “I remember when we were trying to figure this all out as best we could ahead of time. And then Mike was just, like, ‘Let’s just start where we are.’ And I was, like, ‘I love that. That really makes sense to me.’”

She was also moved by their dedication to taking a collaborative approach to their broader mission of facilitating environmental repair by building alternative markets for local farmers.

“In most of my career and life, I have judged things very much on relationships,” Perretti says. “It’s about really seeing the people that you’re working with. Is there a shared value? Is there a mission? Is there a purpose outside of just making money? Because if it’s just that, I’m not interested in working with you. These guys impressed me very, very much. They really put a lot of effort into what they did. And I just clicked with them.”

With River Valley Community Grains as her anchor tenant, Perretti has taken her first step toward realizing her dream of creating an agricultural hub at Marksboro Mills. In addition to the space that houses River Valley, the property includes a large barn/warehouse, a house, and a three-bay garage outbuilding—providing ample space for River Valley to expand its milling capacity and add retail space for their products, as well as those from other New Jersey farms and artisan processors. The house, once the village schoolhouse, will be used by Perretti’s farm manager, who, she hopes, will be integral to bringing more Warren County farmers and land into production of heritage grains. Perretti would also like to bring in complementary tenants, including a baker, which would create an on-site demonstration of the farmer-miller-baker connection that is foundational to the revival of local grains. And while she is overflowing with ideas about how the barn and property could be used for community gatherings, theater, music, and art, Perretti wants Marksboro Mills to evolve in a collaborative way that reflects and serves the needs, desires, and resources of the local community.

• • •

After centuries of absorbing the shaking caused by the steady grinding of heavy millstones, the thick stone walls of Colonel Mark Thompson’s water-powered mill are now silent as are New Jersey’s other once-abundant stone grain mills (see sidebar). Where once an entire building was needed to grind grain into flour, modern small-scale milling equipment grinds hundreds of pounds of grain an hour in a small space without the disruptive vagaries of water flow and ice. This small-mill technology allows for the relocalization of grain production—bringing long-forgotten flavors back into the local marketplace, enabling artisan bakers to return to making more traditional rustic breads, and creating new markets for local grain farmers.

Perretti’s vision of an agricultural hub goes beyond grain production. She sees the site as bringing back the role of small mills—and Cappy’s—as a community gathering place. It also helps fulfill the desires expressed by Frelinghuysen Township residents who responded to Environmental Commission surveys in 1986 and 1989. When asked what they considered to be “most important visually and worthy of protection,” two-thirds of those residents identified old farms, farmland, rural atmosphere, and Marksboro’s historic town center as among their top priorities.

Still, many challenges remain. Growing grain in the Northeast is tricky; high humidity and ill-timed rainfall can lead to lower protein levels and pathogen infections that render grain unsalable for human consumption. Scaling up while maintaining a balance between supply and demand will be a constant challenge. So will overcoming the perception that the organic and local food movements are impractical and elitist—and that they are driven by a romantic desire to return to the past, rather than a commitment to creating an alternative to an impersonal, opaque, global food system that doesn’t fully compensate farmers for their work in environmental repair.

For Perretti and the River Valley team, the goal is to create a positive economic, environmental, social and culinary impact by staying focused on their local community.

“None of us has ever said that we want to get this on every grocery shelf in America. We’re not thinking that way at all,” Perretti says. “It’s, like, think small. Think about repair. Think about maybe doing a pilot program—an illustration of how it could work that could be replicated throughout the state.”

“That’s why I got excited about this project,” she continues. “Because I think this speaks to something different and it speaks to something that communities are hungry for. Something with purpose. Something that connects different aspects of a community. Coming together in a fresh way, a mutually supportive way—and having fun doing it.”

www.rivervalleycommunitygrains.com

NJ’S GRAIN MILL PAST

Once a common sight along our region’s rivers and streams, New Jersey’s early grain mills had various styles of work and payment. Some were merchant mills—larger operations that purchased wheat from farmers, ground it into flour, and then sold that product to the market. There were also small mills that engaged in custom grinding for farmers within a five-to-ten-mile radius of the mill. These millers were often paid with a percentage of the ground grains, which they then kept for personal use or sold. In his book The Early Grist and Flouring Mills of New Jersey, Harry B. Weiss notes that farmers’ visits to the local custom mills also provided them an opportunity to exchange opinions with other farmers and catch up on the latest news.

“IN MOST OF MY CAREER AND LIFE, I HAVE JUDGED THINGS VERY MUCH ON RELATIONSHIPS. IT’S ABOUT REALLY SEEING THE PEOPLE THAT YOU’RE WORKING WITH. IS THERE A SHARED VALUE? IS THERE A MISSION?”

“WHENEVER I SEE A WAREHOUSE LIKE THAT, WITH A FAÇADE LIKE THAT….”

A NEW PURPOSE

Ruthie Perretti was searching for a site for her new business venture and here she was, looking across Route 94 at the white stucco and brick building affectionately known locally as “Cappy’s”. She remembered the building well from her teen years, when her parents had first moved to Marksboro in the 1970s.

“It was part of my ‘village’,” she recalls, and she had always “liked [its] vibe.” The handwritten “For Sale” sign now standing out front offered up a phone number. Ruthie called.

Soon, Perretti, her husband, Eric, and the millers from River Valley Community Grains found themselves walking through the building’s interior.

“It took my breath away,” Perretti recalls. “All the wood rafters. It was just stunning … Packed to the gills with farm equipment.” Built in the 1950s and once home to H.G. Rydell Farm Equipment, it had not been a functioning business for two decades. But, like so many old warehouses and industrial buildings that have fallen out of use across New Jersey, it still had a lot to offer. And Perretti could see it.

“I was very excited by it all. I come from a design background. Old, worn-down patina—that’s the stuff I love the most.” The building’s former owners, now in their 70s and 80s, “had taken beautiful care of the place.” Six months later, in 2020, the purchase became official. Cappy’s would be the home of Marksboro Mills.

Repurposing old buildings can have unique challenges. On the design front, Perretti wanted a partner “who would be a confidante and supporter, that I could throw any question to.” She reached out to Rachael Grochowski, founder and principal of RHG Architecture + Design in Montclair. The two women primarily knew each other through Grochowski’s kids, who were involved in community and arts projects in Montclair and customers of Ruthie’s BBQ, but they had never worked together professionally.

“I [first] showed her the site via cell phone and she loved it,” recalls Perretti. The two spoke at length about the project’s mission, and Perretti sensed the architect “was very mission driven as well. We have similar values, and it made it really easy because I could totally trust her to make decisions.”

Grochowski quickly came on board. “Ruthie’s vision of creating space on an underutilized structure to mill local-grown grains is about healing on so many levels. Her commitment to creating change inspired me.”

The firm’s initial task was to work through creating the space for the grain mill, which included zoning and site plan. “A grain mill isn’t a simple task because of the code requirements dealing not just with food but grain specifically,” says Grochowski.

Design choices such as concrete floors, new window styles, a new garage door and lighting requirements soon followed. Exposed elements were retained and consideration given to future possibilities, such as having small-batch baking on site.

Community healing, repurposing of buildings, and sustainability (economic, cultural, and environmental) are just a few of the words—and values—Grochowski mentions when discussing the project.

“There is something spiritual about reusing existing buildings,” notes the architect. “They hold the history of the past and can also transform the future, but it takes people with vision, like Ruthie, to take a risk to create something for the benefit of the larger whole.” —N. Painter