A Conversation with Alice Waters

Slow-Food Values in a Fast-Food Culture

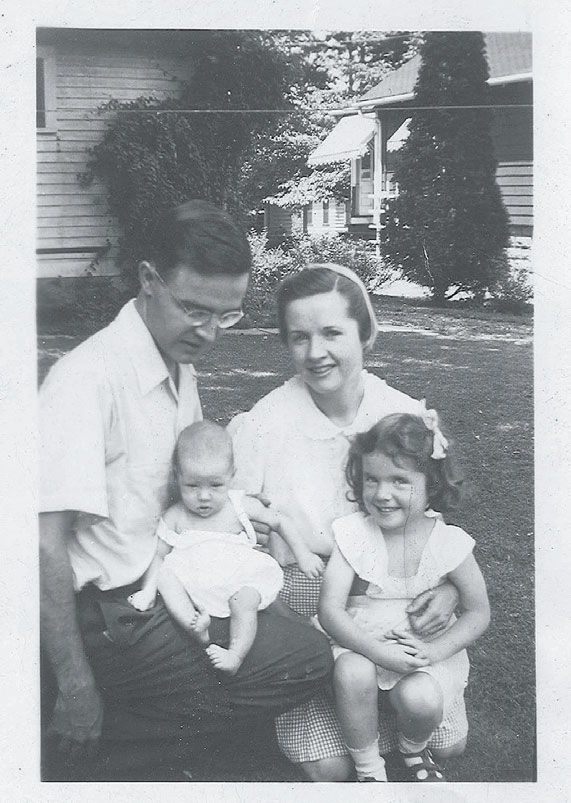

Alice Waters speaks with the cadence of a poet. She talks of food the way one might of a treasured companion, with warm reverence. And while she is most associated with California, her formative experiences happened here, in Chatham, NJ. Alice Louise Waters was born in April 1944, the daughter of a stay-at-home mom with a love for gardening and brown grains and a father who worked for Prudential and who adored jazz and coconut cake.

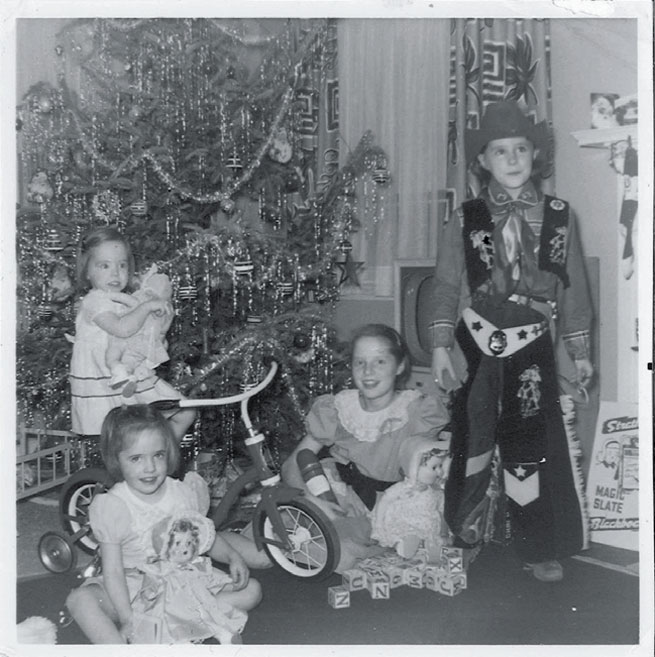

“I grew up at a very different time,” Waters reflects, pausing as if to examine a memory. “I grew up before the birth of industrial farming and fast food, and before television. I really had a different experience as a child. I played in the woods. My town was surrounded by woodlands and swamps and I never went inside. I was connected to nature.”

When Waters thinks about Jersey’s nickname, the Garden State, she reflects on what has been lost—noting that the idea of “Edible Jersey” is a lovely thought. “I know that it was because of the fertility of the soil, and the many, many, many farms that were there, but that really changed at the end of the ‘50s.” [As Brian Schilling, associate professor in the Rutgers Department of Agriculture, Food and Resource Economics, pointed out in Edible Jersey’s May 2017 article about the future of farming in Jersey, we’ve lost roughly 55% of our farms over the last 60-70 years.]

This, Waters feels, makes it vital to seek out the remaining natural places that evoke the world she reveled in as a girl: the woods and waterways, the forested trails and kitchen gardens. “It is the beginning of environmentalism to fall in love with nature,” Waters says. “And when you fall in love with nature, you never fall out of love. We are part of nature and we need to feel that again. It’s our great comfort.”

Her entire career can be considered a testament to that truth.

In the 1970s, if you had walked into a restaurant and asked about the sourcing of the asparagus, you would have been met with a stare. By the latter third of the 20th century, industrial food and big agriculture had taken hold of the American food system, with a guiding mantra of “more, cheaper, faster.” Food, we were told, should be easy on the wallet. It should be convenient and simple to prepare.

Locally sourced? Organic? That wasn’t part of the agenda.

Yet in a Berkeley, California restaurant named Chez Panisse, opened in 1971, Alice Waters sparked a revolution that would rock the gastronomic landscape. Her vision centered on fresh ingredients, sourced locally and served at their prime. It hinged on a quest for flavor, French-inflected, that ultimately led Waters to the organic farm.

In time, she would be lauded for sparking the farm-to-table movement. She would earn accolades as a restaurateur and humanitarian: the first James Beard Award given to a woman for Outstanding Chef in 1992; a French Legion of Honor in 2009; a Presidential Humanities Medal from President Obama in 2014, for “celebrating the bond between the ethical and the edible.” (Michelle Obama’s garden on the White House lawn? That was Waters’ idea.)

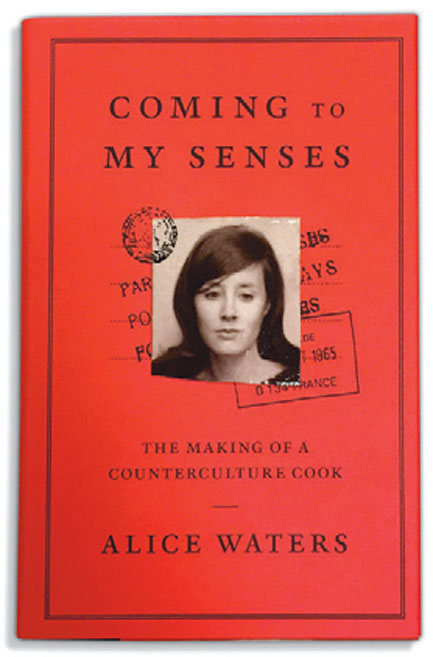

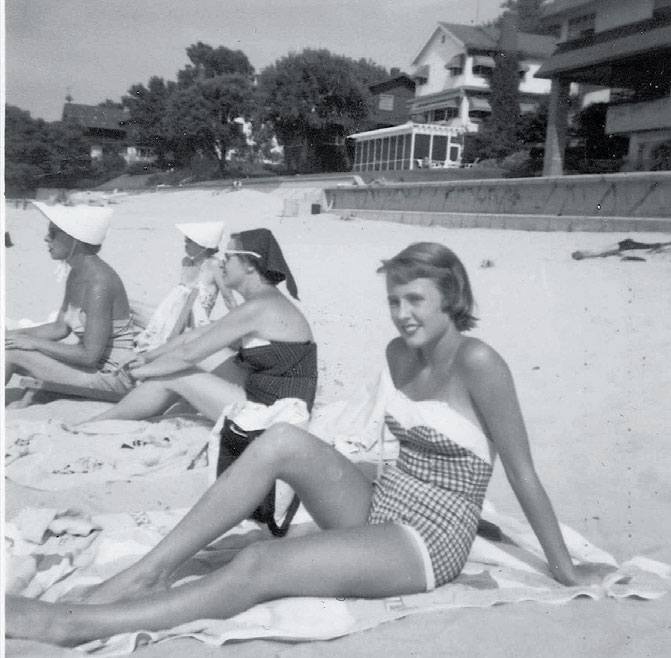

The movement was never the plan. Not at first. Waters simply wanted a restaurant where she could cook food that tasted alive, the way it had during a college trip to Paris and Brittany that she calls a sensory awakening in her memoir, Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook [Clarkson Potter; 2017, with Cristina Mueller and Bob Carrau]. “I was won over in Paris when I was 19 by taste,” Waters says, tracing everything to that experience. “We can find that and then gather at the table and come back to our senses.”

As for the locavore philosophy that would come to be her badge of honor? That was logic: You want better ingredients? You head to the source.

Fast-forward, and this slow-food ethos would define Chez Panisse and redefine the American culinary landscape in the process, establishing a formula now seen on menus everywhere: the shout-outs to local farmers, the embrace of seasonality and philosophy that fine food need not be served on white tablecloths—or even be prepared by a formally trained chef. For as prevalent as New American cuisine has become, it wasn’t a thing until Waters made it so.

That her approach remains profound, nearly 50 years on, points to the seismic shift in food production that occurred over the last century. As Waters wrote in “The Farm-Restaurant Connection,” a 1989 essay in The Journal of Gastronomy, “Most of us have become so inured to the dogmas and self-justifications of agribusiness that we forget that, until 1940, most produce was, for all intents and purposes, organic, and, until the advent of the refrigerated boxcar, it was also of necessity fresh, seasonal and local. There’s nothing radical about organic produce: It’s a return to traditional values of the most fundamental kind.”

As simple, yet revelatory as a plate of just-picked salad greens, Waters’ culinary politics links ethical sourcing, the capacity to generate community at the table and a conviction that healthy food is a human right. Embedded in those values is a philosophy that challenges fast-food culture head on. “The transportation of food, the packaging of food, the farming of food, the factory farming of food—it’s something unconscionable, and the only way to break it is to purchase differently,” Waters says.

PHOTOGRAPHS: COURTESY OF ALICE WATERS

Eating is political

Now in its 47th year, Chez Panisse continues to espouse a slow-food philosophy—and the more one thinks about it, the more radical that seems. As a transfer student at UC Berkeley in the mid-1960s, Waters fell in with the Anti-War and Free Speech Movement that rocked the campus and ricocheted through the media. Students staged sit-ins and pushed back against the lingering paranoia of McCarthyism. They decried the Vietnam War, and mounted a countercultural pushback. Chez Panisse rose up amid this backdrop, its menu a response to what Waters perceived as an attack on pleasure by the establishment.

As David Kamp writes in The United States of Arugula [Broadway Books, 2006]: “Chez Panisse wasn’t a retreat from politics—it was politics, a representation of what American food could be if people weren’t complacent about gassed, flavorless tomatoes and frozen TV dinners.” With Waters as guiding force, Chez Panisse came to symbolize the antithesis of all that. It was a place where people came together and talked politics and truth and art. It was a place where revolutionary values were debated and defined over prix-fixe feasts.

Notably, the kitchen always made room for strong women to work alongside strong men. The first meal was cooked by Victoria Wise, a philosophy Ph.D. with no formal experience. Waters’ long-time pastry chef was close friend Lindsey R. Shere, who would go on to author the cookbook Chez Panisse Desserts, and whose almond tart, served on the restaurant’s opening night, is the stuff of legend. Alumna over the years include Peggy Smith of Cowgirl Creamery, and chefs Suzanne Goin and April Bloomfield, among others.

“I never thought about it back then,” Waters says. “I didn’t think of myself as a woman in a man’s world. I just wanted to have this restaurant and I knew that there were restaurants run by women in France. I didn’t think about it as unusual.”

Nevertheless, she created a progressive model of leadership and sought a synergy between male and female energies. Currently, six of eight leadership positions at Chez Panisse are held by women. “I didn’t intend that,” Waters says. She admits, though, to being pleased. “Particularly at this moment in time, we do have to pay attention. Men and women should make the same for the same job. I’ve always said that.”

Early on, Waters also believed that to be fully awakened, one had to reconnect with the senses—yet Americans were eating factory-farmed burgers in their cars. To Waters, this signaled a breakdown in the social fabric. She craved the conviviality of a shared table where views and dishes could be savored. She craved flavor that catapulted one into the present tense.

This fed her eventual conviction that sustainable, local and organic sourcing is the only ethical choice, well before others caught on or New American cuisine had a name. “I want way more than organic, but the standard is high enough for me that it rules out a lot of . . . well, practically all of the corporate, cruel animal farms and butchering factories.”

Asked whether she sees echoes of the Vietnam-era counterculture in the present moment, Waters is decisive. “I do see it. It feels like the ‘60s to me: the government lies, and the wars,” she says. “When you watch 18 hours of Ken Burns’ ‘Vietnam,’ you really understand that all of the things we were feeling back then were valid. Young people have an urgency that we felt back in the ‘60s. They want to do something, and they are trying to see where they can fit in.”

As she talks about this, Waters grows animated, her voice centering like a gathering storm. She is heartened that, like her, today’s revolutionaries are finding their voices through food. “A lot of people are feeling the draw to farming, and I’m very excited about that. Very excited.”

“We thought that we could change the world by being against something. Now we can change the world by being for something,” she says. “This is a delicious revolution, and once you get involved, you can’t let go of it. We have a choice: We can support the people who are doing the right thing, or we can support the people who are doing the wrong thing. We spend our money in that way every single day, so there is a lot of power involved.”

Yet when Wal-Mart touts organic, and fast-food restaurants boast healthy menus, how can consumers stay the course? Waters’ advice: Ask questions before you buy: “How big is the farm? Is it organic? How do they treat their farmworkers?” Then buy from the farmer, not the middleman. “I want to buy directly from the person who is doing that work and keep him or her in business.”

That Waters views shopping for the restaurant or for a simple dinner at home with friends in much the same way is not coincidence. Her original mission at Chez Panisse was always to build community around the table. “Eating what’s in season. Eating with family and friends. Celebrating the harvest. Including children at all times. Complete connection to nature and the care of the soil because that’s where your food comes from. These are values from the beginning of time, and we’ve always held them, until recently. And then: greed. And then: the industrialization not only of our farms, but of our schools. That’s the very dangerous place where we are right now.”

As for the idea that her approach is too expensive or that local, organic sourcing isn’t viable for the average consumer? “These are myths. We have to understand that corporations are trying to advantage themselves and indoctrinate our children. ‘You don’t like anything but pizza. You want to watch television while you are eating.’ I’ll tell you: Every child that I know would rather have an interaction with a person than a television.”

The same can be said for adults. “Francine Du Plessix Gray said that the dinner table is the primary right of civilization, and I’ve thought about that so much. Taking the time and attention to pass the food, to share the food, to have a conversation,” Waters says. “How do you teach slow-food values in a fast-food culture? We have to look at the values that we are digesting with the food.”

See Alice Waters live: On March 2 at 7:30pm, William Paterson University will host “An Evening with Alice Waters,” part of its yearlong Food for Thought series. Waters will speak about cultivating slow-food values in a fast-food world. For tickets, visit wp-presents.org.

ALICE WATERS’ ADVICE TO THE INDUSTRY

On cooking with a purpose: “We are part of a very big, important movement that is thinking about the future of this planet. We are stewards. We are powerful, important voices. A fundamental awareness is emerging, and we’re all part of a bigger picture.”

On valuing every role: “When you have a mission that is righteous and important, it makes every job in the restaurant valuable. The dishwasher is valuable. They’re part of this. They’re helping us build something new.”

On sourcing sustainably: “When we started buying food from farms 47 years ago, it was directly from the farmer. There was never an issue with food costs. The money we spend is on preparation of that food at the restaurant.”

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY OF ALICE WATERS

Chez Panisse rose up amid the backdrop

of ’60s counterculture, its menu a

response to what Waters perceived as an

attack on pleasure by the establishment.

PLANTING SEEDS

These days, Waters is as well known for Chez Panisse as for Edible Schoolyard, the nonproft she founded in 1995 that advocates for the creation of school gardens and edible education. IfWaters has her way? Every child in America will one day enjoy free, organic and sustainable school meals, including breakfast, a hot lunch and snack. It’s about health, sure, but it’s also about feeding the next generation of empowered individuals and anchoring communities.

“When we buy directly from farmers and bring the farmers to the schools, we bring their values in through the cafeteria door;” Waters says.’’l want to make that path direct so that rural farmers can And a valid economy for themselves, and a purposeful one too. Twenty percent of the population is in school. So, if we purchase that food from the people who take care of the land, it would begin this revolution—it could happen global, truly.”

When a child is provided with healthy food, it’s a way of saying: you’re seen, and you’re valued. In a disconnected time when meals are accompanied by TV and tweets, that’s a radical idea. “We have to really reinvent what we serve our kids,”Waters says.

Her track record suggests that it’s possible. Launched with a single garden in Berkeley, Edible Schoolyard has grown to connect more than 5,500 programs. Beth Feehan, New Jersey’s Farm to School coordinator; credits Waters with kick-starting a movement that was overdue. “Alice Waters sparked a revolution that has become an army and continues to grow” Feehan says. “This has changed the landscape for looking at food in schools drastically.”

While Farm to School is distinct from Edible Schoolyard, Feehan credits high-profile individuals like Waters with creating the framework for a garden-based education that made it possible. “It is absolutely the central educational tool to enlighten children to healthy food. A classroom presentation about a carrot does not compare to tasting a carrot that’s pulled out of the ground.”

Compared to just 10 years ago, Feehan notes a marked increase in the number of New Jersey teachers bringing garden education to the classroom. “The schools are demanding it. The PTAs are demanding it. Superintendents are embracing it and putting it in the budget. ‘The movement is also gaining broad public support. In 2017, New Jersey residents were able for the first time to support Farm to School and School Gardens on their state tax returns.

With an eye on cultivating global citizens, Edible Schoolyard has recently been focused on teaching children about the world through food—discussing the climate and geography of the Middle East, say, while serving hummus and spicy carrot soup with warm pita that the children cook themselves. “It’s validating a truth about children and food,” Waters says. “They like foods, all kinds of foods, when they’re introduced to them in a way that empowers them.”

The way Waters sees it? Schools are our last truly democratie institution, and the place where revolution can begin anew.”You know, 85% of kids in this country don’t have one meal at the table. This is why I am focused on school lunch.Taking the time and attention to pass the food, to share the food, to have a conversation. To show those children that we love them. I think we have to do something dramatic. I do.”

WILLIAM PATERSON UNIVERSITY DISHES UP ‘FOOD FOR THOUGHT’

One need only consider the proliferation of academic food-studies programs nationwide to realize that the next generation is food-focused (no, not just on Instagram.) It has become a lens through which students study the world around them, from public health to the sciences to the humanities. This is heartening to those of us who view food as a prism, a medium with the capacity to shine light on nearly every aspect of the human experience.

As the saying goes, we all eat. Every day. With this in mind, William Paterson University in Wayne has been engaged in a yearlong programming series dubbed “Food for Thought.”

“I saw that there were at least 12 courses that dealt with food in some manner,” says Jane Stein, executive director of performing arts, who designed the series. “The global aspect, the culture, food and community, communicating food, nutrition, food insecurity. It was a thread that connected all of the units of the university.”

“Food for Thought” launched during the fall semester with a theater production from artsy agitators the Guerilla Girls. The collective of masked feminists, who maintain anonymity—wearing, yes, gorilla masks—staged a production about the history of women in food, from M.F.K. Fisher to Southern food legend Edna Lewis.

In the months since, the series, which is open to the public, has attracted luminaries, including former Gourmet editor Ruth Reichl, who spoke in November about food safety and the future of food. She also enjoyed some Jersey hospitality in the form of an Italian sub from Brother Bruno in Wayne. “She’s not a diva, and she loves all kinds of food,” Stein says. “She started to eat it, and it was just this look of pure contentment and enjoyment on her face, eating the simplest food.”

Other highlights include a day with famed forager “Wildman” Steve Brill [pictured]. During hikes across campus, he opened students’ eyes to the edible world hidden beneath their feet. “The thrill of discovery was just intense,” Stein says. “Finding a mushroom that you could eat and tasting things that you walk by on the ground. There was a little leaf that tasted exactly like fresh corn.”

This spring, the series continues with a keynote from Jersey native Alice Waters, to be held in conjunction with the university’s Distinguished Lecturer series. (See page 30 for an exclusive interview with Ms. Waters.) Stein, who views Waters as a culinary hero, expects her to talk about her unconventional path into the culinary world, as chronicled in her new memoir, Coming to My Senses [Clarkson Potter; 2017, with Cristina Mueller and Bob Carrau]. She will also discuss her vision for the future of food in the United States. “I hope that this will be a great capstone of the series,” Stein says.

Other events will focus on food justice both near and far. On March 27, writers Francis Lam, Helen Rosner, Chris Schonberger and Jordana Rothman will discuss the intersection of food writing and social responsibility. On April 4, former Savoy owner and harbinger of farm-to-table in Manhattan, Peter Hoffman, will join members of the environmental design collective SPURSE to discuss their cookbook, Eat Your Sidewalk. It posits that a “bottom-up” embrace of urban foraging is the next wave in sustainable eating.

Melina Macall, co-founder of NJ-based Syria Supper Club (“Shared Meals, Shared Humanity,” Edible Jersey, Fall 2017) will also host two spring events under the umbrella of “We All Eat.” In the fall, she focused on Cuba, highlighting her research into the after-effects of a collapsed food system and solutions that rose in its wake. On March 21, she will bring Syria Supper Club to campus for a Syrian lunch and discussion about how displaced people can establish roots through food. On April 18, the “We All Eat” will conclude with “Bringing Your Cultural Heritage to the Table,” which will look at the stories and cultures behind iconic American foods, tastings included.

As a food-justice advocate and adjunct professor for the University, Macall draws a line between such hands-on experiences and the classroom. “I teach about food justice, and the students learn about the US food system and the impacts of that food system nationally, globally and directly on them,” she says. “They also learn about other systems around the world, including Cuba. It creates an awareness. Through all of this, we learn about advocacy.”

Stein suggests a reason that culinary topics are so powerful in supporting that aim. Like music, food is a language that everyone speaks. —J.H.

For a complete listing of upcoming events in the “Food for Thought” series, visit wpunj.edu/wppresents/wp-presents-series/food-for-thought.html.