Congress Hall’s 200 Years of Farm-to-Fork History

THE BIG HOUSE BY THE SEA

Strolling the stately grounds of Congress Hall, it’s easy to picture the majesty of the bygone grand-hotel era in Cape May. One can almost see cloche hats perched on flappers among the potted palms of the Brown Room, or Victorian gentlemen with starched collars relaxing with cigars in the wooden rocking chairs that grace the colonnade overlooking the Grand Lawn.

During 2016, the restored seaside resort has been celebrating its bicentennial birthday and its long history of hosting U.S. presidents, celebrities (John Philip Sousa conducted concerts on the lawn and wrote the “Congress Hall March” in its honor) and the social elite. Today, it’s known for its rich history and luxurious but relaxing atmosphere—yet this grande dame by the ocean has an equally long culinary history.

Early Farm-to-Fork: From “DIY” to Fine Dining

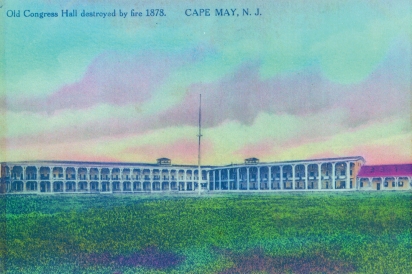

First opened in 1816 by Thomas H. Hughes, the hotel, originally called “The Big House by the Sea,” was much larger than the typical inns and taverns that served visitors to what was then known as “Cape Island.” In fact, at three stories high and 100 feet long, it was one of the largest hotels in the world at the time. Yet locals dubbed it “Tommy’s Folly,” doubting it would ever find enough visitors to fill its rooms and break even, let alone find success. However, the skeptics were proven wrong by the constant flow of Philadelphians looking for a “rugged” but beautiful vacation spot by the ocean. The hotel flourished. When a fire burned it down only two years later, Hughes simply rebuilt it and made the “Big House” even larger. To feed all of these visitors, the hotel’s kitchen shipped some items in via stagecoach but, like most businesses at the time, it relied primarily on the plentiful produce and products of the Cape May area.

“When Congress Hall opened, by necessity, produce was local,” explains executive chef Jeremy Einhorn, who oversees the hotel’s Blue Pig Tavern. Einhorn did extensive research in Congress Hall’s historical menu archive to recreate dishes for the hotel’s bicentennial birthday dinner in the ballroom this past summer. “In the time before refrigeration and rapid transit, it was extremely difficult to get anything outsourced. Everything that was served was either an imported luxury, such as tropical fruits, or local produce.”

Before the 1830s, dining was not yet a sophisticated affair at Cape May’s inns and hotels. Vacationers were sometimes expected to help in the preparation of their own meals, as documented in 1829 by a guest of the nearby Atlantic Hall, even assisting in the slaughter and butchering of local mutton.

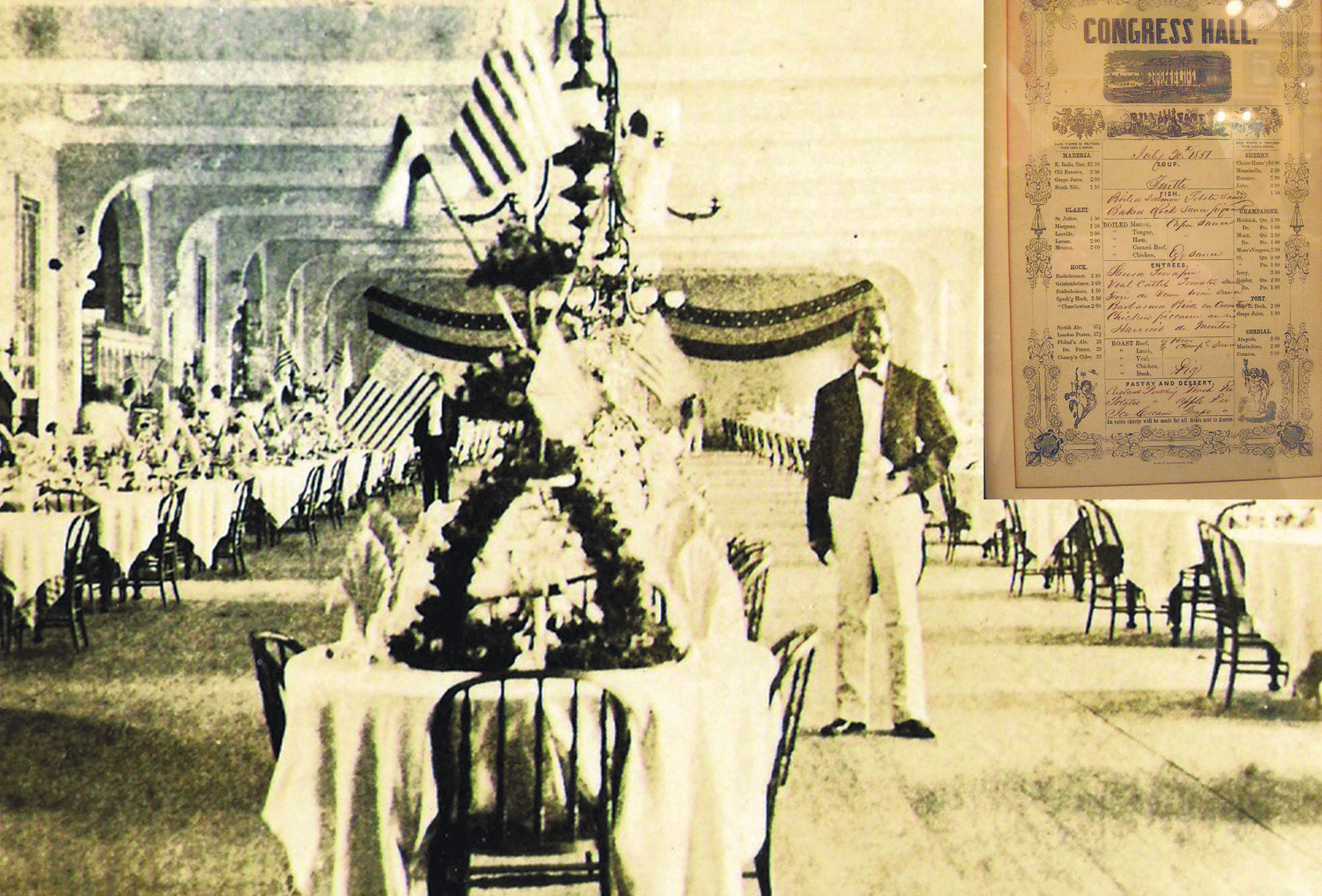

In 1826, Hughes sold Congress Hall and set his sights on a higher ambition; in 1828 he was elected to the House of Representatives— inspiring the new owner, Samuel Richards, to give the hotel its current moniker, Congress Hall. Shortly after, a more genteel and wealthy clientele began to appear in Cape May, which brought major changes to Congress Hall’s dining scene. The hotel hired chefs and attendants who could properly prepare and serve more sophisticated cuisine. Although beef dishes were the status symbol of fine dining at the time, Congress Hall’s menu continued to favor locally sourced items. For example, a “Bill of Fare” from 1851 lists roast beef near the bottom of the entrees, but “headlines” delicacies such as Turtle Soup and Stewed Terrapin.

“What really struck me in my research,” says Einhorn, “was that Congress Hall would also promote their local meats on their menus. They were bragging about their farms, even back then.” During the 1850s, this “bragging” may have also been personal: Congress Hall’s fourth owner, Waters B. Miller, also owned a nearby farm that supplied the hotel with most of its produce

By the Victorian era, dining at Congress Hall meant “fine dining”—and that was synonymous with the French way of doing things. “By the late 1800s French was the fashion, and French style was a lot more pomp and circumstance,” says Einhorn. “If you look at the old-style banquets with French service, a skilled server would carry a dish out, arranged carefully on a platter, and would present it to the guests tableside.”

In his research, Einhorn came across one French-sounding item that appeared again and again in the late 1800s—not only on Congress Hall’s menus, but on menus all over the country: macaroni au gratin. “Otherwise known today as macaroni and cheese,” Einhorn laughs. “It looks like it’s been ubiquitous Americana for some time!”

Presidential Guests and “Underground” Kitchen Staff

In 1878, another fire leveled Congress Hall once more. It was rebuilt yet again into its current incarnation, this time with fireproof brick. Upon reopening in 1879, its fine reputation attracted vacationing United States presidents. Ulysses S. Grant was a guest here (he would only eat his meat “cooked to a crunch” and refused any poultry, according to the kitchen’s notes), and in 1883, President Chester A. Arthur stopped briefly to shake hands with Congress Hall bathers. In the summer of 1891, President Benjamin Harrison rented out the entire first floor, and that year Congress Hall was dubbed the “Summer White House.” President Harrison’s favorite food was the plentiful and well-known delicacy of Cape May’s waters at the time: oysters. His wife claimed he would eat them three times a day if he could.

The guests weren’t the only famous people at Congress Hall. In 1852, Harriet Tubman worked as a hotel cook in Cape May to help raise money for her slave freeing operations. Some historians believe that, since Congress Hall was such a large employer at the time, it is extremely likely that Tubman was employed in the kitchens of Congress Hall that summer. Even more interesting, by this time Congress Hall was regularly welcoming wealthy guests from below the Mason-Dixon Line—Tubman could have been bankrolling her slave-freeing operation by cooking for unsuspecting slaveowners.

From the early 1900s until the beginning of the following century, the hotel experienced a roller coaster ride of booms and busts, with a renovation in the early 1920s under owner Annie Knight. Congress Hall eventually fell into disrepair and was closed to guests in 1991. In 1995, Curtis Bashaw acquired the property; it is due to his vision and passion for history that the details of the hotel’s heritage, both culinary and otherwise, are so well preserved today.

Restoring a New “Golden Age”

Throughout its 2001 restoration, Bashaw and his team intended to retain as many original fixtures and features as possible. A stash of original china from its Victorian heyday was discovered, packed away in a box. Reproductions were soon commissioned from the same two companies—still in business today—that had produced the 19thcentury originals.

In a move that mimicked the supply arrangements of Waters Miller’s day, Cape Resorts (Bashaw’s parent company, which runs Congress Hall and other local hotels) purchased Beach Plum Farm, located only three miles from Congress Hall. The farm, along with its two sister farms, now supplies all of Cape Resorts’ properties with almost a half a million dollars’ worth of fresh produce every year, as well as meats such as Berkshire pork and chicken, eggs, herbs and even flowers.

“I love it, and I do think that I’m on a little bit of a mission,” says Bashaw, who can often be found at the farm pulling weeds and helping with the harvests. “The tripod of our economy down here in Cape May County was always tourism, agriculture and fishing,” he adds. “In recent years, the agricultural portion kind of went a bit fallow. But now, given the fact that people want food that’s wholesome and that they know the pedigree of, they really see the value of the farm and what we can supply to all our hotels on a regular basis. And because we have this farm, most deliveries are only a few miles, just as it was back in the Victorian era.”

Although colder days are now setting in, Beach Plum will continue to supply Congress Hall throughout the winter with hothouse lettuces, potatoes, meats, eggs, dried herbal teas and pickled vegetables and tomato sauces, made and preserved from the summer’s harvest. Guests at Congress Hall are supplied with handmade soaps and lotions made with rosemary, mint, lavender and lemon verbena from Beach Plum’s large herb garden and can warm themselves by the fire with wood from the farm’s dead or fallen trees.

The Brown Room, a chic, Roaring Twenties–style space that was originally home to Cape May’s first post-Prohibition cocktail bar, serves cocktails infused with both Beach Plum’s produce and Congress Hall’s history. In summer, some artisan drinks include cucumbers, berries or herbs grown on Beach Plum’s acres.

Even in the colder months, bartenders are always looking to incorporate the farm’s products. “Our cocktail menu changes from season to season, and we try not to recycle the same ones. If we get enough pumpkins from Beach Plum this year, I will be using them for our Pumpkin Martini,” says Stephen Mannino, food and beverage manager at Congress Hall. “But I am also working on trying to incorporate more from the farm this year than last.”

The bar has also developed a few cocktails inspired by past presidential guests. The Drunken Theatrics is a concoction of Bulleit bourbon, lemon juice, strawberry simple syrup, ginger beer and bitters that was inspired by Franklin Pierce, known to have a passion for whiskey. The Whiskey Smash combines Woodford Reserve bourbon, lemon juice, blackberry simple syrup and mint in a tribute to a cocktail that James Buchanan and his Democratic cronies may have enjoyed. Both will remain on the menu until the New Year.

As far as Bashaw is concerned, Cape Resorts and Congress Hall will not be resting on their culinary laurels. Currently, he’s investigating the possibility of bringing dairy farming back to the area, with visions of supplying his hotels with local yogurt, cheese and ice cream. He also dreams of one day creating a local agricultural “gap year” program for high school graduates.

“I think there is a new spirit of entrepreneurship amongst the kids,” says Bashaw. “If what we’re doing here can inspire others to say, ‘I could do that,’ I just think that would really reinforce the economy down here, our agriculture. “

Regardless of how many new ideas get implemented, Bashaw continually draws inspiration from Congress Hall’s history.

“Benjamin Franklin once said, after the Constitutional Convention, that we have a republic, ‘if you can keep it,’” says Bashaw. “The funny thing about Congress Hall’s history is that it had nine owners in 200 years, but there were times when it failed and there were times where it had a golden age. Right now it appears to be in another golden age, and I could say, ‘I’m going to make it last forever!’ But I can’t make it last forever. I can only do what I can do to keep it.”

Congress Hall

200 Congress Place, Cape May

609.884.8421