A Taste of Chambersburg's Past at the Club Condado

An advertisement for the Club Condado’s New Year’s celebration on December 31, 1939, promises a “De-Luxe Supper” and an “Extra Fine Holiday Floor Show, Music and Dancing.” A few miles outside Trenton on River Road, the club occupied a striking building in the Spanish Colonial Revival style, then popular in Southern California: red clay roof, white stucco walls. Bartenders in white coats shook up cold Manhattans and martinis. Tables for hundreds of guests filled the dining-room floor, with waiters in black tuxedos dotting the scene, delivering steaks and cocktails to the crowd. The stage hosted a big band and vocalists singing popular songs—“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” maybe, or “And the Angels Sing”—and men and women filled the dance floor, floating on fine food and drink at a place as beautiful as the famous nightclubs in Miami or New York City.

My great-grandparents, Jules Gasparri and Lucia Frascella, owned the Club Condado from 1939 through 1955. Jules, formerly Tullio, had immigrated from Spoleto, Italy, in 1914 as an 18-year-old who spoke no English and had only a grammar-school education. He laid railroad tracks and enlisted in the US Army, serving in World War I and receiving a Purple Heart. My family describes him as a “Jersey country gentleman”: gardening, hunting and breeding boxers and Great Danes and ornamental birds.

Lucia, one of eight children in a big Italian-American family, grew up in Trenton’s Chambersburg neighborhood, also known as the ’Burg. By that time, the ’Burg was a well-established Italian-American enclave. Families sat on the front steps of their row homes when the weather was warm, the children running in the streets. Every September, the neighborhood celebrated the Feast of Lights, parading behind a statue of the Madonna through the streets. For decades, nearly every corner of the ’Burg seemed to host an Italian restaurant or bakery or pizza shop: the Italian People’s Bakery, Roman Hall, DeLorenzo’s Tomato Pies.

In 1928, long before they dreamed of the Condado, Jules and Lucia converted the first floor of their Elmer Street row home into a Prohibition-era speakeasy. Jules churned out alcohol in the upstairs bathtub with his brothers-in-law, doctoring it with food coloring to concoct whiskey and gin. Decades later, my grandfather—Jules and Lucia’s son—met Governor Richard Hughes, who had visited the speakeasy long before. He told my grandfather, “Your father made better booze than any restaurant today.” Lucia did all the cooking at Elmer Street, dishing out lasagna and spaghetti to feed hungry college kids from Princeton and Rutgers; she’d slip the cops a free plate of pasta when they passed by the building.

Once they went from the ’Burg to the Club Condado, though, the rib-sticking macaroni got displaced by fancier fare. They hired a proper chef, Giuseppe, who cooked a few Italian dishes—the Condado was known for its chicken cacciatore—but the kitchen focused on American fine dining: steaks and chops, shad roe, king crab, lobster. Artistic by temperament, Giuseppe had a habit of storming out of the club in fits of rage. On those nights, Lucia assumed control of the kitchen. Giuseppe would be welcomed back the following night with open arms: Good cooks were hard to find, and Giuseppe’s work made up for his unpredictable temper. On the land behind the Condado, Jules grew vegetables to serve in the dining room, and Lucia canned the surplus tomatoes to last the kitchen all year—farm-to-table, decades before Chez Panisse.

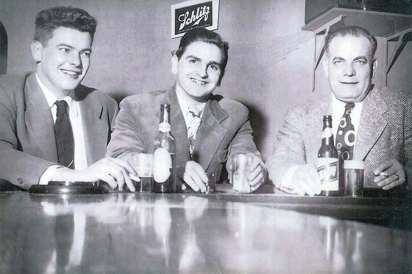

Beneath the Condado’s cosmopolitan glamour, it was a family affair—the mom-and-pop made good. Jules, known to his staff as “the Duke,” greeted his guests and kept tabs on his employees. After closing the club at two-thirty in the morning, he would take a handful of staff out for breakfast at a diner down the road. Lucia oversaw the kitchen and kept tabs on the bookkeeping. My greataunt Roseanne, now 92, remembers working every job in the place: cooking, bussing and waiting on tables, even singing with the band. Even the family’s boxer was put to work, keeping the bar floor clear of stray potato chips.

My grandfather Jack did his time at the Condado too, bussing tables and working behind the bar. One summer vacation, home from college, he worked as the club’s manager, allowing his parents a well-deserved break. When his stint ended, he came to his father with a business plan, offering to buy the club from him when he wanted to move on. But Jules was adamant that his son would have a different life: He would be a doctor or a lawyer. While my grandfather was finishing his senior year of college, Jules sold the Condado. The new owners kept the club open for just few years, unable to cope with flood damage to the property.

One big element of any immigrant story is the wish Jules had for my grandfather: that his children would have a better life than he had. Another piece of the story is assimilation. The Club Condado was elegant in a way that was recognizable to any American—and in no way specific to my great-grandparents’ Italian-American culture. The ’Burg today bears little resemblance to the old neighborhood. In the latter half of the twentieth century, a combination of shuttered factories and “white flight” drove most of the former population to the suburbs, and the restaurants followed: Marsilio’s has a restaurant in Ewing; DeLorenzo’s has outposts in Hamilton and Robbinsville. No one in my family speaks Italian except my mother, who has pursued it only in the last decade.

Our family’s cultural lineage from Jules and Lucia is most evident in the way we treat food: the heavy plates of antipasti at every family gathering, my grandfather’s generosity with red wine, the biscotti my Aunt Ro sets out when she serves me tea. My mother taught me to make ricotta gnocchi from a recipe she received from Lucia, her Nonni. The ingredients and instructions for handling the dough are part of my family inheritance—but the pleasure of welcoming people into my home and serving them this handmade dish is just as much a part of my birthright.