Meny Vankin Cooks from the Heart at Montclair's Mishmish

The Soul of an Israeli Chef

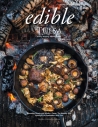

When you taste Meny Vankin’s shakshuka, an Israeli dish of eggs cooked in tomato sauce, you can pick out flavors and try to fathom what makes his version so good. There’s garlic. There’s chopped cilantro. There’s olive oil (from Spain), the herbal fragrance of za’atar, the tang of the feta that fills a tub in the open kitchen of Mishmish, Vaknin’s 46-seat restaurant in Montclair (opened December 2014). But still, you know you’re missing a crucial ingredient. And to understand what that ingredient is, you have to understand Vaknin and his experience with food— most of all, the food of Israel.

Vaknin, 33, was born in Yeruham, a town in Israel’s Negev Desert. His parents came to Yeruham in the early 1960s, with a wave of fellow Jewish immigrants from Morocco. “Yeruham was a developing town,” Vaknin recalls. “In the beginning there were a lot of North African Jews: Tunisian, Persian, Moroccan, a melting pot. Later on, Russians and Ethiopians came. The culture was small town. Everybody knew everybody. Everybody tasted each other’s food. Jews from all over North Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and even India settled in his hometown. “I’m influenced by Indian cuisine,” Vaknin says, recalling the assorted flavors of Yeruham with a kind of awe.

“For Moroccan Jews, the kitchen is the main part of the home,” Vaknin explains. “Growing up, everything was based around food. My grandmas and aunts were women who cooked, and they did so with great pride.” Vaknin recalls his great-aunt’s house, where “at any point of the day you could see at least two things being made—I’m talking big pots that could feed 20 people.

Vaknin’s family cooked Moroccan Jewish food. “My mom taught me everything I know about spices,” he says. Cumin, turmeric and ginger are staples. On Tuesdays, his great-aunt always made a pot of fresh couscous. On Fridays, his mom made beef meatballs (with eggs encased inside) and harissa-spiced fish stew, a dish that is on the menu at Mishmish today.

For holidays like Passover, a sheep was slaughtered at his uncle’s farm. After the blessing rabbi left, Vaknin would spend hours breaking down the animal with his uncle, from the time he was just six years old. “Then we ate sheep for the next two weeks,” Vaknin says with a smile. “That was my town.”

A memory of his neighbor, Ester, shows the hospitality and culinary prowess that defined the community of his early years. Ester cooked frena, “a big, thick pita good for six or seven people,” in an ancient oven—powered by stones and an open fire. “She would make 200 on a Friday afternoon and send them to people for shabbat. I would come home from school or, later, from the army, and my aunts would send me with a case of flour to Ester. I would come back with freshbaked bread. Ester was a tiny little lady. All over her house, in every bedroom, was proofing frena.”

Life in Yeruham was simple, rural and nothing like what Vaknin would encounter when he moved to New York City at 22. He worked in an uncle’s restaurant. That gig never took off, so Vaknin found work at Rose Water, a restaurant in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

Rose Water was, for Vaknin, a flipping of his “culinary switch.” The restaurant had a Middle Eastern focus at first, but evolved to become a New American restaurant. Vaknin loved the nature and scale of the work; some days Rose Water served 200 people during brunch. He admired the passion and professionalism that the owner, chef John Tucker, brought to his food, wine and customers. This experience sent Vaknin to the French Culinary Institute at 27. After graduation, he helped open the famed Boulud Sud as a line cook— another restaurant where food, wine and customers were given great respect, the same kind they got back home in the Negev Desert.

Now, a visit that was supposed to last six months has lasted ten years. Vaknin absorbed technical and business skills during long shifts in Daniel Boulud’s Manhattan kitchen. In 2014, he realized his dream and opened Mishmish. By then, he had found the crucial ingredient to his shakshuka.

The food at Mishmish is Moroccan-Jewish and Mediterranean. Though modern Israeli food has taken off in recent years (as shown by the success of cookbook author Yotam Ottolenghi and restaurants like Zahav in Philly), Vaknin is hesitant to characterize his food as Israeli, even though many Israeli dishes are on the menu. In his hometown, “Israeli cuisine” was an idiosyncratic bricolage of cuisines imported from the reaches of Europe, Asia and Africa. Further, during his 12 years in the United States, Vaknin has been influenced by even more cuisines, notably Mexican. What Vaknin does at Mishmish is prepare food he remembers from Israel using French technique— sometimes adding an Indian accent, a Mexican twist, or another element that makes sense to him. For example, Vaknin takes sabich (a roasted eggplant sandwich) and shawarma—both traditional—and turns them into tacos.

At Mishmish, regulars fill a six-chair counter overlooking the kitchen and watch Vaknin create. He is relaxed in the kitchen, with the cool, focused air of a jazz musician—reaching to pick up bread with tongs, spinning to season a lamb burger on the grill—and moves with a casual fluidity. As Vankin adds his crucial ingredient to a single-serving pot of shakshuka, you feel like you’re in his home.

In a way, you are. The smells are garlic, onion and charred eggplant—the same as those of the kitchens in which Vaknin grew up. The vibe is come-over-for-dinner. There are faded family pictures on some of the walls, including a series of a young Vaknin and his grandmother preparing sfenj, Moroccan donuts.

“The way the women I grew up around treated their food, and the way they treated the people who ate their food, was so soulful,” Vaknin says. “At Mishmish, I am working from both ends of the spectrum: the fine, the classic, the French; and then the grandma: the rustic, the cultural, my roots, my legacy.”

And that’s what makes his shakshuka. You can taste the shakshuka’s crucial ingredient in Vaknin’s other dishes. You can taste it in the cool burn of housemade harissa, in the satisfying char on grilled halloumi cheese. You can taste it in the tang of labneh, in the faint brine and Platonic softness of octopus and in the depthless flavor of an Old World, mind-opening hummus. Vaknin’s crucial ingredient comes all the way from Yeruham. The crucial ingredient is a timeless blend of warmth and tradition. The crucial ingredient is soul.

Mishmish

215 Glenridge Ave, Montclair

973.337.5648

mishmishcafe.com