A Jersey Girl and the Disappearing Recipes of Italy

Katie Parla invites me to meet at L’Angolo Divino, a small but lively wine bar near the Pantheon, close enough for a tourist’s convenience, yet not easily discovered amid the tangle of narrow streets that is the heart of Rome. L’Angolo Divino is a popular spot for ex-pats, with 40 seats, give or take, and jazz on the sound system.

Here, Massimo Crippa is the third-generation owner. Crippa has taken his family’s once-pedestrian wine and liquor shop and turned it into an important modern space, selling local wines, biodynamic and organic. His customers are savvy. Some refuse a certain vintage because they disagree with the politics of the vineyard owner. Others are discovering and rediscovering the classic wines of Tuscany, traditional wines that have not changed but that are suddenly fashionable. Crippa rarely takes a day off, and his longtime customers chide him for this. A forthright woman from Maine, who has boldly signed a year’s lease on a nearby apartment in an expression of ideal retirement, reminds him that he deserves a personal life. With his curls, his Roman nose and plaintive eyes, Crippa has the countenance a sculptor would love. He likely couldn’t make it through a five-minute pose. Crippa is busy; he is a businessman and a sommelier, and wine always offers something new to learn.

I have dined in the past with Katie Parla in Rome; indeed, her gracious willingness to guide strangers through her adopted home has provided me with an indelible first memory of the eternal city. It was late afternoon, and Parla scurried me along Via Cavour—past the pompous white marble wedding-cake structure that is the monument to Italy’s first king, Victor Emmanuel, past a plot of ancient ruins, a collection of crumbling columns and monuments and cats amid the hustle of traffic and modern discourse. I wanted to gawk, but Parla had a purpose. She wound me like ribbon to Via dei Chiavari, to the doors of Antico Forno Roscioli. A bakery has been in this spot since 1872. Here, the pizza is cut to order, sold by weight, and Parla, speaking for me, stood in line and made our request. We paid and spilled dutifully out of the tiny, bustling shop. It was now just past dusk, suddenly quiet. The two of us stood with our pizza on the weathered cobblestones outside. This was my first food in Rome.

I have dined for years on pizza on the sidewalks of New York, and I have folded my share of slices in New Jersey. Both New York pizza and New Jersey pizza are often fantastic, the rightful standards, in the States, against which all other pizza is judged. But the pizza of Rome, like everything else in the eternal city, is in another category altogether. Parla had ordered pizza rossa, the crust so thin as to be magic, the intensity of the tomato sauce unexpected. In trying to describe it, I can think only of the words I used, and heard often, in Italy—the short-cut words of people trying to communicate when they don’t share a language. Unbelievable. Not possible. Bellissimo.

Parla had chosen pizza, appropriately, to introduce me to Rome, one Jersey girl to another.

As a child, Katie Parla had been intrigued by Rome— the gladiators, the ruins, Caesar, Latin. To live in Rome was, and is, a dream come true. Yet, she has also learned that the Italy of her expectations is not the Italy of Rome. That Italy, the artisanal Italy, exists in the south.

Parla, who grew up in Princeton Junction, has now spent 16 years in Italy. She has become an exuberant ambassador. Parla has a degree in art history from Yale and a master’s degree from the University of Rome, where she studied Italian gastronomic culture. Tasting Rome, her cookbook released a few years ago (see Edible Jersey, Winter 2017), shares her loves for the gastronomic complexities of the eternal city—the neighborhoods, the markets, the Jewish food culture, the Libyan food culture. Tasting Rome was named International Cookbook of the Year from the International Association of Culinary Professionals. Today, Parla lives in Rome and is an authoritative source for publications worldwide, including The New York Times, Conde Nast Traveler and Saveur, and an expert consultant for a number of television production crews. Parla also is a personal guide, offering exclusive food tours, archeological tours and art tours of Rome. People respond to these bespoke experiences—Rome, especially, can overwhelm.

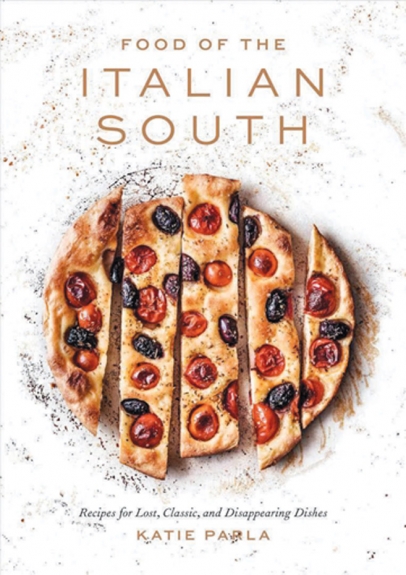

This month, Parla is releasing another impressive work: Food of the Italian South, Recipes for Lost, Classic, and Disappearing Dishes (Clarkson Potter, March 2019).

As a child, Parla had been intrigued by Rome—the gladiators, the ruins, Caesar, Latin. To live in Rome was, and is, a dream come true.

Yet, she has also learned that the Italy of her expectations, an Italy where all the shoes and the jewelry and the sweaters are hand-crafted, where the ravioli and the spaghetti are homemade and where cheesemakers and winemakers abound, is not the Italy of Rome. That Italy, the artisanal Italy, exists in the south. In Rome, people dine out or stop at the supermarket, and the pasta is prepackaged.

“That romantic vision still exists, but you really have to look for it.”

Parla’s new book is a reflection of that journey—of her many trips to the country, to Campania, Molise, Calabria, Puglia and Basilicata, to the regions of Italy often overlooked by tourists.

These areas are less populated, not so industrialized. In Parla’s travels, she sought authenticity: that granny who makes a unique pasta shape, the last shepherd in the village, etc.

Southern Italy, she has discovered, holds its own eternal secrets.

The book features 85 recipes, with photos, of the endangered classics from the Old Country, including the real origins of Italian wedding soup. (Parla notes that most Italian Americans came from the south of Italy.)

Parla is not the only one concerned about disappearing dishes. New food safety standards—i.e. the rules created in Brussels for the European Union—make it difficult for a small farm in Sicily, for example, to sell artisanal products. In Tuscany, I met a woman who has trouble finding organic produce and travels an hour each week to a farmers’ market in Florence to do so. At L’Angolo Divino, the ex-pats are talking about a Financial Times exposé of the mafia’s involvement in the Italian food supply. Olive oil has become more profitable than cocaine, and the involvement of organized crime has led to knockoffs of buffalo mozzarella, of organic wheat, of Parmesan, of extra-virgin olive oil.

Parla tells me that most people travel just once to Rome. I am surprised; I find myself wanting to return every year. Yet, I understand what she’s saying. Without the right guides, without people like Parla and Crippa, Rome can be exhausting and garish and mediocre. I have had bad spaghetti at a café near the Vatican. And it is disconcerting to leave a work by Bernini—he is the sculptor behind one of the three fountains in Piazza Navona—only to stumble upon a sign for McDonald’s, located nearby in Piazza delle Cinque Lune.

In Rome, the Testaccio neighborhood, Parla will tell you, is a bastion of local food culture. Testaccio was, for nearly a century, the slaughterhouse neighborhood, and the restaurants here specialized in cucina povera, the cheap bits: tripe, offal, intestines. In Testaccio, in search of a classic Roman experience, I dined at Cecchino dal 1887. The restaurant has red tile floors, white tablecloths and wooden chairs with high backs. The waiters are disapproving and maddeningly deliberate. I glimpsed, in the kitchen, the arm of a rotund chef.

I ordered, at the recommendation of the waiter, a braised artichoke, which was regally presented and tender, followed by bucatini all’Amatriciana with a sauce made with pork cheeks. I was struck by the elegance of this dish—the balance, how the center held, first bite to last. The waiter recommended a red wine from Casa Romana Colonna, the vineyard of a noble family that has been making wine in Lazio, about an hour’s drive from Rome, for 300 years. It was 6 euros a glass.

In other words, lunch was perfect. The experience was topped off by what I assume is another authentic Roman experience: Luigi the cabdriver expecting that his exceptional driving skills also entitled him to a full-on kiss on the lips.

Parla began her book tour last month with a dinner in South Beach with Bobby Flay. She will end her US book tour on the East Coast. On her last day in the States, as is her custom, she’ll have pizza with her friend Dan Richer at Razza Pizza Artigianale in Jersey City, which serves, according to The New York Times, the best pizza in New York, and where the pizza rossa is made with crushed New Jersey tomatoes.