GLOBAL PRODUCE: NEW JERSEY CROPS FROM FARAWAY PLACES

Peppered among the tapestry of million-dollar farms growing Jersey corn and tomatoes are some small-time farmers specializing in the kinds of ingredients you won’t readily find at the local grocery—produce such as sticky corn, jujube, gongura, bitterball and kittley.

These unfamiliar fruits and vegetables are native to the home countries of New Jersey’s expanding ethnic communities. The farmers growing them often have agrarian roots in those countries, and in this fertile state they have adopted, they feel pulled back to the land to grow the tastes of home.

It’s as difficult to pin down the number of ethnic farms in New Jersey as it is to define what crops are “ethnic.” The potatoes and cabbages considered staples of an American diet were brought here by Irish immigrants. The Italian eggplants and basil that grow so well in Jersey summers were once considered ethnic, brought to this region with the Italian immigrants who coveted them. More recently, ever-growing Hispanic and Asian communities have made cilantro, mustard greens and hot peppers popular here.

Now, a new wave of farmers is expanding the definition of Jersey Fresh. Some farms are just an acre or two, offering picky-our- own options for members of their communities across the Eastern seaboard. Alongside them are large-scale farmers who see ethnic vegetables as a way to expand revenue by selling to the state’s growing roster of ethnic grocery stores and restaurants.

“We’re getting more calls from both ethnic growers and other growers looking for some more information on unusual crops,” says Richard VanVranken, who runs Rutgers University’s New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station in Atlantic County. He noticed the growing interest in ethnic crops years ago and helped develop the worldcrops.org website to assist farmers in growing and marketing the produce.

The potential is great, yet there are major obstacles. Farmers must understand the market so they don’t accidentally flood it and inadvertently drive down prices. That’s why some small growers are secretive about what they grow, afraid that a larger farm could adopt their crops and edge them out.

“It’s almost easier to grow the things than to market them correctly,” VanVranken says. “If we talk too much, then everybody else gets that idea and there’s market saturation.”

Introducing foreign crops in New Jersey also means running the risk of exposing them to local pests and conditions for which they are not resistant. The eggplant and basil varieties grown in this state have been bred to be resistant to area diseases, but new crops are vulnerable. Some farmers have been completely wiped out during new crop experiments and forced to start over.

Yet, they persist. The reasons why vary, of course, but they come down to some universal basics: cravings for childhood tastes, love for the land and the joy of gathering with others.

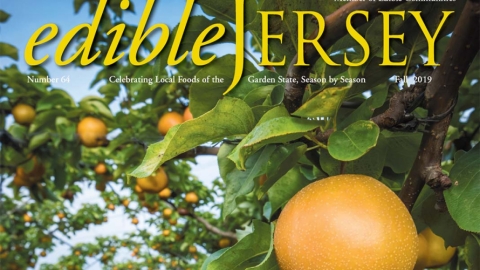

THE FAMOUS PEARS OF HAMILTON

Chong Kim did not forget the sweet taste of singo pears in the 15 years he spent working in New York City grocery stores and textile factories after leaving South Korea. The grapefruit-sized pears are prized for being crispy, sweet and juicy all at once, and they provoke a particular nostalgia, since they are customarily shared with others.

His obsession with recreating that taste in New Jersey is why his 160-acre Evergreen Farm is one of New Jersey’s most successful ethnic farms. Whole Foods carries the pears in stores as far away as Chicago, Texas and Canada. The year-round farm in Hamilton also attracts tour buses full of people of Korean, Chinese and Japanese origin on weekends—sometimes 3,000 visitors in a day—and a steady stream of locals on weekdays for its other crops, too: Korean grapes, chestnuts, jujube, black beans, soy and sticky corn (a starchy variety of white corn speckled with purple kernels).

But success did not come easily for owner Kim and his wife, Sunyi Cho. Kim, the son of a farmer in South Korea, was still working in the city when he bought a small patch of land in South Jersey in 1998 and a handful of trees from a supplier in California. He spent every weekend on the farm with his wife and son, tending to the young trees. When they began to bear fruit three years in, deer tore through the field, and Kim had to restart.

“We bought a fence, but it took two weeks to arrive and the deer ate it all during those two weeks,” Kim recalls. “It took one year to grow and restart.”

Then, when the trees were just five years old, a dry August spoiled the fruit. And in his 12th year as a farmer, all the trees died unexpectedly. At that point, Kim said he threw in the towel. He recalls that his son told him firmly, “No more farm. I hate the farm.”

But then Kim stopped in at a local agricultural office and noticed a poster about a type of bug that had ravaged the area’s apple orchards, and put two and two together. Equipped with knowledge about what had ruined his pear trees, he started again with a plan for protecting the trees using small amounts of pesticides. Today, the farm has relocated to a 160-acre spot in Hamilton Township, and visitors come from as far away as California to try Kim’s famed pears.

Kim says his father taught him the technicalities of growing Korean pears, which are heavy due to their size and must be protected from winds so they don’t fall. Kim has manipulated the trees to grow in arches. Not only does it make for a beautiful landscape to roam under when picking the pears, but it also protects the fruit from strong winds during nor’easters and hurricanes.

Though growing the pears in Jersey poses challenges, Kim says the climate is even better than South Korea for the fruit. When the harvest is complete in November, the pear trees must be left alone for 100 days—a time period when the weather must be neither too cold nor too hot. New Jersey, it turns out, is perfect.

“The sea breeze is very good for the tree,” Kim says.

Over the years, Kim has used his taste buds to guide him, calling on his memory of the perfect pears he had in Korea to continually improve his crop. He aspires to be the world’s best Korean pear farmer, and he knows that success requires trying harder and harder each season.

“It is very hard for me, but when people are happy to eat our fruit, I’m really happy,” Kim says, before sending me home with six crates of pears to distribute to friends and family. “I hope that every American tastes my pear.”

Ridge gourd at TIKSmart in Pemberton

Eggplant at TIKSmart in Pemberton

FRESH GONGURA IN PERMBERTON

TIKSmart is easy to miss: A dirt road leads to the farm’s single acre of crops, which are tucked behind rows of soybeans and next to a much larger alpaca farm in Pemberton. It’s a smalltime venture that is mainly a hobby for the group of Indian professionals, including a doctor and an IT project manager, who run it. During the planting season, they take turns driving to the farm from nearby cities to tend to the field.

The IT project manager is Hema Kanthamneni, who helps operate the farm. She leads me past plants of okra, tomatoes, heirloom eggplants and Indian pumpkins to rows of roselle leaves, the farm’s main prize. “Gongura,” as it is known in the Telugu-region of central India, is a staple of the region’s cuisine that is valued for its medicinal properties. It adds a distinct lemony zip to curries and lentils, as well as a healthy dose of vitamin C and iron. Gongura is used in a variety of ways in Telugu cuisine, including as a pickle, but finding it fresh in New Jersey is a challenge.

“When I go to the farmers’ market, I get kale, Swiss chard and beetroot. But when I go to the Indian store, all the options have pesticides. The vegetables are coming from Florida or some other place and were cut weeks before,” she says. “I want to have fresh, organic Indian vegetables, too.”

Word about the farm, which is just a few years old, has spread primarily through informal WhatsApp groups in the Indian community. The farmers are giving away most of the vegetables, charging only for the gongura, as they wrap up their second year in operation.

They don’t expect to make much money from the venture, but that isn’t their focus. Instead, they are eager to cultivate a lifestyle of healthy living. They plan to clear land for outdoor yoga and a picnic area where families can spend some time in nature after picking their vegetables.

“We know very well we are not going to make money, but at the end of the day, we are happy that we are eating whatever we grow here,” Kanthamneni tells me as she and the others sit down for a midday meal of homemade egg biryani.

Prab Tumpati, a doctor who is one of the owners of the farm, explains how they have managed to collect materials and farm equipment from Craigslist and eBay to get by on a tight budget. They once loaded up free horse manure from a nearby farm into their minivans when they were scouting out ways to improve the soil.

The sweat and toil that has gone into building up the farm has clearly been a labor of love: Tumpati estimates that he and his partner, Srinivas Indukuri, have made an hourly wage of about $1.50 this season for all their time and investment. But, they both come from families of farmers in India and seem to relish recreating that agrarian lifestyle, if only for a few hours each weekend, in New Jersey.

“My friends go to the gym. They pay the gym, then they use their energy from their muscles, and they use electricity to run the treadmill,” Tumpati says. “Me: I’m getting a workout, I’m producing something we can eat, and we’re making a few dollars here and there. It’s fun.”

“My friends go to the gym. Me: I’m getting a workout. I’m producing something we can eat, and we’re making a few dollars here and there. It’s fun.” —Prab Tumpati of TIKSmart Farm

Farming crew at TIKSmart Farm in Pemberton. BACK, LEFT TO RIGHT: Papireddy Tiyyagura, Sreenivas Koonadi, Srinivas Indukuri, Srinivasu Buddi FRONT, LEFT TO RIGHT: Kasee Viswanadham Tumpati, Hema Kanthamneni

Farming crew at TIKSmart Farm in Pemberton. BACK, LEFT TO RIGHT: Papireddy Tiyyagura, Sreenivas Koonadi, Srinivas Indukuri, Srinivasu Buddi FRONT, LEFT TO RIGHT: Kasee Viswanadham Tumpati, Hema Kanthamneni

Amadu Gray at World Crops Farm in Vineland

Bitterball, World Crops Farm in Vineland

KITTLEY AND BITTERBALL IN VINELAND

Saturdays are the day to visit World Crops Farm in Vineland. That’s when the sleepy 12-acre farm turns into “party central,” longtime customer Abbey Johnson tells me as owner Morris Gbolo rings up her purchase of kittley, a bitter, grape-sized variety of eggplant that is traditionally cooked in West African stews.

“This is like the gathering place for all of us. When we meet here, we feel happy,” she says. “We encourage the children to come. This brings us closer. It reminds us of where we came from.”

Johnson explains that people who come from New York City bring African clothes and other wares that can be hard to find in parts of New Jersey. Others from Maryland and Washington, DC, also make the trek to spend time together and pick vegetables such as collard greens, habañero peppers and eggplants. Johnson is Nigerian and Gbolo is Liberian, but she says the differences in their cultures matter less in New Jersey, where they all come together as Africans.

Gbolo’s face lights up as Johnson talks about the Saturday gatherings.

“In Africa, when we go to the farm, we feel happy. In the US, we have a lot of stress. It’s work, work, work, but at least sometimes we take off time. My friends come, and it gives a sense of release,” Gbolo says.

By helming the farm, Gbolo has become a leader in his community. But it’s just one way that he gives back. He also holds a full-time job as a case manager at Atlantic City Rescue Mission, which helps people who lack housing. He returns to Liberia as well to provide assistance to people there.

Keeping the farm going hasn’t been easy. Gbolo has had health troubles and crop troubles: Last year, many of his crops suffered in the heavy rains. But he is encouraged by the visitors who come from as far as Ohio, eager for a taste of home and some time with kindred people. Gbolo says he has shipped vegetables to Michigan and North Dakota. The most popular request is for kittley and bitterball, another eggplant variety that can be eaten raw but is often stir-fried or added to stews.

Gbolo also likes to have access to the foods of his native Liberia. His passion for agriculture began as a young child, observing his elders farm. He studied agriculture and forestry at the University of Liberia before a civil war drove him and his wife to Ghana. When he came to Atlantic City in 2002 in search of opportunity and a stable life, Gbolo’s knowledge of African crops helped him land a job with Rutgers University’s agricultural program. He eventually secured a federal grant to help him start farming.

World Crops remains a part-time venture: It’s closed in the winter, and Gbolo and his wife both work full-time jobs to make ends meet. Still, he says he is content.

“The smaller the farm, the less income you have, but also the less you need. It has advantages and disadvantages,” he notes. “For me, I love it. I can grow this for people to have it. That’s what I love to do.”

Owner Morris Gbolo, World Crops Farm in Vineland

Owner Morris Gbolo, World Crops Farm in Vineland

More than a dozen farms in New Jersey grow produce specifically for the ethnic market. For more information about the farms in this story:

EVERGREEN ORCHARD FARM

1023 Yardville Allentown Rd, Hamilton Township

609.259.0029

evergreenfarm.us

TIKSmart

225 Fort Dix Road, Pemberton

215.450.0309

gongurafarm.com

WORLD CROPS FARM

330 Tuckahoe Road, Vineland

609.289.5153

worldcropsfarm.com

Growing interest in global foods and ingredients traditionally used by immigrants from Latin America, Asia and Africa are driving shifts in food retail and the sale of fresh produce. Rutgers’ Agricultural Experiment Station has teamed up with the University of Massachusetts’ Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment and other organizations to create a resource for information on the growing, marketing and availability of crops popular among immigrant populations in the northeastern United States. Learn more at worldcrops.org.