Dennis Foy's Enduring Roots

New Jersey’s own farm-to-table founding father

As the sun climbs up toward the windows of chef Dennis Foy’s Lawrenceville art studio, it fills the space with a honeyed light. Brush in hand, the chef mixes colors and then turns his attention to the line between land and sky. When he is not at d’floret, the 24-seat Lambertville restaurant he owns with wife and business partner Estella Quiñones-Foy, you can often find him here.

Writers like to draw neat lines between every aspect of a chef ’s life and the kitchen. Foy resists such easy characterizations. “People get caught up in the dichotomy between cooking and painting,” he says, pausing to showcase a study for an oil painting. “For me, cooking and painting have the same sensibility of expression, but cooking is collaborative. With painting, it’s very singular.”

Their point of union comes in an enduring drive to create, to explore the range of the senses. “I want to live an engaged life,” Foy says, explaining a work ethic honed during his Army service in Vietnam and a University of Pennsylvania master’s degree. Everything in his life centers on that impulse, which feeds his characteristic intensity. The result is an influential career spanning four-plus decades.

In a three-star New York Times review, Foy garnered praise for cooking “whatever is best that season and in the market that day.” That was in June 1978, when he was just 26 and running the kitchen of his brother John’s Tarragon Tree in Myersville. There, the pair forged the framework of a new philosophy: it was farm-to-table before farm-to-table had a name.

Across a string of restaurants in New Jersey and Manhattan— Mondrian, EQ, Bay Point Prime, and Dennis Foy’s Lawrenceville Inn, to name a few—Foy moved on to define a seasonal sensibility that now dominates American cuisine. Along the way, he influenced other chefs, including Craig Shelton of Ryland Inn and Debbie Ponzek of Montrachet and Aux Delices.

“My first restaurant was called Rosalie’s Kitchen, and it was a former location of Dennis Foy’s,” recalls Marilyn Schlossbach, the Jersey Shore’s culinary queen. “What sold me was the edible garden that surrounded it. Dennis and Alice Waters were two of my earliest influences.” There was Alice on the West Coast and Dennis Foy here. A fundamental shift was under way.

Ingredient-Driven

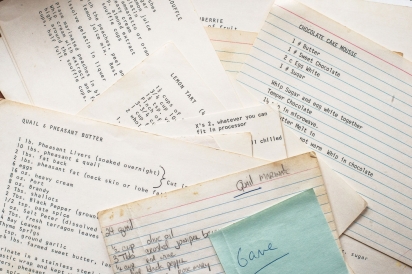

Foy’s culinary training began in his mother’s kitchen, where cooking centered not on recipes but on ingredient lists. He still has many of them, stowed in a file with other gems—like handpainted Mondrian menu covers. “My mother was a tremendous cook,” he recalls. When the partnership with his brother broke apart, Foy opened his new iteration of Tarragon Tree in Chatham. Fast-forward to 1981, and the Times would write a different kind of profile of the chef.

Showcasing his passion for the local ingredient, even then, “A Chef’s Day Out at the Quail Farm” reads like modern food writing. In the story, we meet a team of chefs foraging at Griggstown Quail Farm, Foy among them. We see him sourcing trout along the Delaware. Natural talent turned to desire for mastery, and Foy completed a one-week internship under nouvelle cuisine luminary Michel Guérard. “It was so critically important to me, because he was all about color and texture,” Foy says. “I wasn’t thinking in those terms at the time, but the artist side of me got it immediately.”

He proceeded to cook through the entirety of le répertoire de la cuisine alongside the late Bob Long, the Tarragon Tree chef who would go on to achieve four stars at the Frenchtown Inn. “Bob was a gifted and obsessive perfectionist,” Foy says. In part, he attributes their shared rigor to the expectations of East Coast diners, Francophiles who were dining at La Grenouille and Le Cirque. “Food is taking off in America,” he says. “Travel is taking off. So, culturally, you have this mix.”

Chef Debra Ponzek, who did an externship at the Tarragon Tree and then served as Foy’s executive chef at Toto in Summit, recalls the period vividly: “Dennis was ahead of the curve,” she says. “When I worked for him, my perspective was as an upcoming chef. I didn’t realize the impact. Dennis was really the first person who did farmto- table.” She still credits him as a mentor.

Through their 18-hour days, Foy challenged Ponzek to express the natural talent that he recognized in her immediately. “He actually went to the farms,” Ponzek says. “Any bird or game that I would break down, it always had feathers on it. The flavors I love today are from working with Dennis all those years ago.”

“There was a Puritan ethic to it,” Foy says of the time. “If I could do things at my best possible level, it would be as close to God as I could get.” The kitchen, however, only tells one side of the story.

Chasing the Muse

To shop with Foy at the Trenton Farmers’ Market is to understand something essential about the man. Wandering on a fall Thursday, we pick up Terhune Orchards spinach and Cranberry Hall parsnips, Sandy Acres turnips and Amish chickens. Come spring and summer, he’s here three times a week. The banter between chef and farmer is accordingly warm and familiar.

“I can’t tell you how much fun I have knowing who I’m buying from,” Foy says. Tellingly, they all call him Dennis.

At Sandy Acres, he admires the butternut squash, then chats with owner Henry Estenes about the relative virtues of glass versus plastic greenhouses. Glass has improved markedly in recent years, in both quality and in price. The implications aren’t lost on Foy. “Without this market, I don’t think some of the farms would survive,” he says, appreciative of the tight margins that define success for farmers in an expensive state.

In turn, those farms support healthy restaurants—a collaboration Foy sees as critical. “I think about the history of what we did,” he says. “The fact that this market has survived all these years—and not only survived, but thrived—is an extraordinary statement about the growth and awareness of farm-fresh product, and I think New Jersey was on the map doing that before anybody else.”

Leaving the market, we drop the chicken at d’floret, then wind our way up the Delaware River. There’s only one place Foy will buy eggs, and it’s Rockhall Acres Farm in Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania. Owned by a husband-and-wife team, it’s a gorgeous labor of love.

Like Foy, Saul Ramos has a military background. He and wife Valerie also manage a bucolic homestead that supplies 85 to 90 percent of the family’s meals. “I can buy from almost anyone, but considering the service to our country and the quality—it’s just fabulous,” Chef Foy says. “They’re the best eggs, and it’s because the chickens are running all over the 50-acre organic farm.”

The heirloom-breed eggs come in shades of sky blue and clay. There are steer, kunekune hogs, even a stray guinea hen that’s made a home here: the eating is so good that an outsider moved in. “Our relationship is built on friendship and deep respect,” Foy says of his decades-long connection with Ramos. That his eggs make for gorgeous pasta and pastry is a bonus.

Farm-to-Table Grows Up

When his eponymous restaurant closed in Lawrenceville a few years back, a casualty of the real-estate market, Foy proclaimed that he was done cooking. But Quiñones-Foy knew better. Challenged to find the perfect spot—something Foy was convinced would never happen—she focused on Lambertville. When he tells the story, he laughs and shakes his head. She had done it. The river city is the perfect culinary home for an artist-chef.

Foy describes d’floret’s kitchen—particularly in the morning—as a place of contemplative stillness. The ingredients have been sorted and the room is quiet. He is alone with the early daylight, and it’s something like a sanctuary. Scanning ingredients sourced just hours earlier, he begins to plan the evening’s menu.

Asked why farm-to-table dining has continued to surge, Foy points to agricultural industrialization and GMOs. “The reason people are so keen on farm-to-table, or even putting gardens in their backyards, is to have access to food where they know the source. It’s about health.” Because if you strip away the flannel and mason jars, the reclaimed wood and metal fixings, what remains of farm-to-table is what matters most: the farmer, the chef, the food, and the plate. It’s an old way of cooking, the original alchemy of seasonality and heat—and, here, it is a decidedly grown-up experience.

As diners float into the restaurant, the lights dim and music fills the space. Quiñones-Foy welcomes the guests, who settle beneath a selection of Foy’s recent paintings, a modernist departure from his representative landscapes.

Conversation fills the room. Then the food begins to emerge from the open kitchen. Notes of truffle and sage turn handmade gnocchi into comfort food. Fennel and tomato confit melt beneath Atlantic cod. The evening is a dance, methodical yet intuitive. At the point where the singular and collaborative meet, Foy’s creative passion is rendered visible on the plate.

Watch for a joint art show this spring featuring Foy and jeweler/photographer Joseph Romanowski. For details, visit goldtinker.com.

d’floret

18 S. Main St., Lambertville

609.397.7400