When Life Gives You Lemons

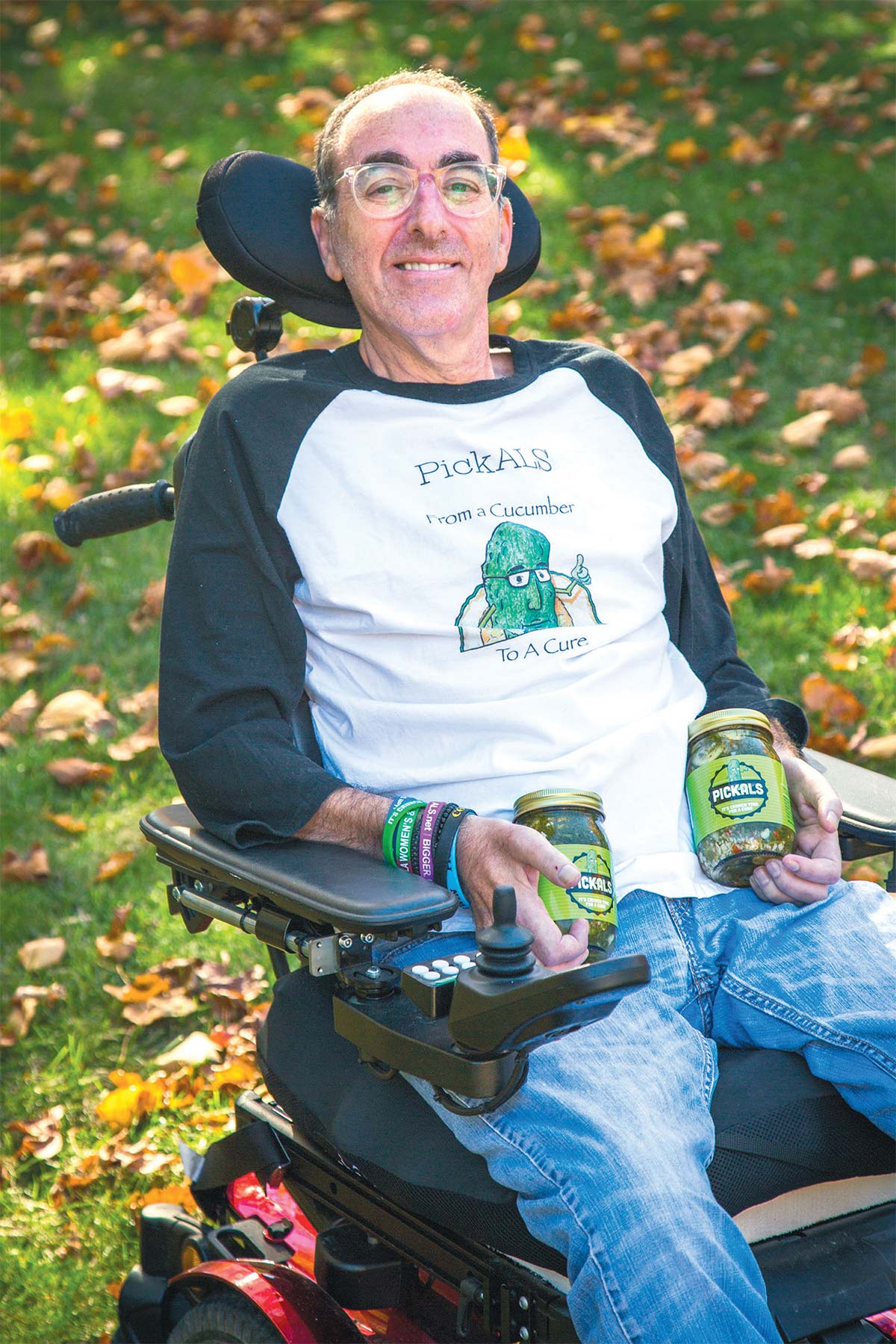

When Arthur Cohen was diagnosed with ALS, he decided it was crunch time for a cure. Meet the crunchy, garlicky, salty and ever-so-sweet legacy known as Pickals.

Pickles should make you smile.

They bring zest to the plate and the palate. Pickles are the bonus to any lunch, the perfect accessory, that little extra surprise that reminds us that we eat for pleasure as well as for sustenance. Pickles are fun.

It is therefore revealing that when the Arthur Cohen began grappling with the ALS diagnosis he received in November 2013, his attention turned to pickles.

Cohen, a portrait photographer who died of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in August at the age of 61, had enjoyed making his own pickles for family and friends. As ALS inched its way through the muscles of his limbs, the progressive neurodegenerative disease stole Cohen’s ability to take pictures. He could no longer pursue his life’s work.

So he told his wife he wanted to switch gears and make pickles. But not just as a hobby. For real.

Even in the best of times, it’s not easy to start a small business, let alone a venture with an idealistic goal. Yet when Arthur Cohen told his wife he wanted to spend whatever time he had left making pickles to raise money for ALS research, she was immediately on board.

“One of the interesting things about being terminally ill is you realize, ‘What’ve I got to lose?’” says Janet Coviello. “You develop a sense of fearlessness.”

They called their new product “Pickals,” pronounced just like “pickles,” but with a new ending and a serious purpose. “It was one of those things that lit a fire under both of us,” Coviello recalls. “I really believe it kept him alive. He was so passionate about it, and he made so many friends and brought people together. “

The couple began discussing the idea in the spring of 2014. They tested the waters with pickling parties in the kitchen of their Maplewood home, with Cohen instructing friends on the finer points of how much garlic and what kinds of cucumbers to use. Coviello, an advertising copywriter, added her own creative flourish to the project with tag lines such as “Crunch Time for a Cure.”

Cohen was no chef. Coviello says their two grown children recall him making only three dishes: grilled pizza, barbecue chicken and lasagna. But about 10 years ago, he decided to make pickles with the cucumbers from their garden, and he began scouring recipes and tweaking the proportion of vinegar or salt until he developed his own cold brine.

Arthur Cohen

“Typical of Arthur,” Coviello says, noting her husband’s tenacity and enthusiasm for the project at hand, as well as his success.

“Initially, he made pickles from the cucumbers he grew in the backyard,” Coviello says. “That was how it started. As he got more into it, he would go to indoor farmers’ markets all year and buy kirby cucumbers. He liked them because they were always crisp. He was particular about how thick to cut them. He started making more and more pickles.”

“He used to give them to friends,” she says. “I can’t tell you how many people tell me they’re the best pickles they’ve ever had. They’re fresh-tasting, super crunchy, garlicky, salty. I don’t like when pickles are soggy and olive green. These stay really crunchy. They’re just really good.”

Cohen’s pickling parties took off and word of mouth spread through the ALS community.

“There was an awful lot of camaraderie and humor,” says Beth Daugherty, a neighbor and close friend of the Coviello-Cohen family, recalling the early days of Pickals. “Arthur had incredible charisma and energy, and he got people excited about things, and it was fun going to their kitchen. I loved the cause and I loved the pickles.”

In 2015, Patriot Pickle, a company that makes pickles for restaurants and commercial venues, offered the use of its factory in Wayne. Pickals became a real-deal product. At first, friends volunteered their time at the facility in Wayne, greatly helped by the co-owner of Patriot Pickle, William McEntee Jr.

“For a long time, he donated cucumbers and garlic and labor,” Coviello says.

Daugherty was among the friends who helped at the factory.

“It used to be we would go and pack ourselves,” Daugherty says. “Now we have an agreement with them and we pay a co-packer to produce them.”

Cohen’s enthusiasm and graciousness could almost make his friends forget the bad news that led to the creation of Pickals. But not quite. ALS is brutal.

“It’s a science fiction disease,” Coviello says. “You are dying in slow motion.”

Medical websites, such as that of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, are filled with the outlines of ALS symptoms. ALS often strikes in middle age, with symptoms that seem to be minor, at first: muscle weakness, atrophy and cramps, stiffness, a tendency to trip and fall. But patients also may present with more alarming symptoms, such as slurred speech and difficulty chewing and swallowing. All those symptoms eventually await ALS patients, progressing until they are frozen in their own bodies, unable to move or speak or swallow or breathe. But they generally do not lose the ability to understand and remember, so they are fully aware of what they are going through.

Most people with ALS will die within three years of diagnosis, but the ALS Association reports that 20% of patients will live for five years, 10% will live for 10 years, and 5% survive for 20 years or more.

Arthur Cohen knew full well what the last few years of his life would bring. Faced with the impending loss of everything except the love of family and friends, he said to his wife, “Let’s make pickles,” realizing that eventually he would lose even that.

“Arthur was able to do less and less over time,” Coviello recalls. “He went from making the pickles and being the leader, and then he couldn’t chop a cucumber anymore. Then he was going to the factory to oversee things, and then he was going to the factory in a wheelchair, and then, he was an observer to this thing he created. And that was hard for him.

“He also felt, not guilty, but, he was relying on volunteers and friends who were doing this out of the goodness of their hearts,” Coviello says. “But I would tell him that this was a way for his friends to help him. People don’t know what to do in a situation like this. They want to help, and they don’t know how. So, this was how.”

“He had this vision of trying to make something positive out of all this,” Daugherty says. “It was a great idea, and a great thing for Arthur to do, to make something positive out of this horrible disease. He found a way to bring people together.”

As president of the nonprofit Pickals Foundation board, Daugherty is part of what Cohen called the organization’s “Brine Trust.” She is proud to say Pickals has raised $250,000 for ALS in the past two and a half years, through fundraisers as well as pickle sales.

Initially, Pickals donated proceeds to the ALS Association, which became a household name in the summer of 2014 as the beneficiary of the Ice Bucket Challenge, which raised $115 million. Later, Coviello and Cohen decided to send the comparably modest proceeds from Pickals to smaller organizations that needed it more.

Two Massachusetts-based organizations caught their attention: ALS Therapy Development Institute (TDI), a nonprofit biotech research company in Cambridge that Coviello said has done groundbreaking research and is “very small and streamlined,” and Compassionate Care ALS, a nonprofit in Falmouth, which supports ALS patients and their families. The motto for ALS TDI is “ALS is not an incurable disease. It is an underfunded one.” Among the organization’s research projects is a Precision Medicine Program, which uses genome sequencing, surveys, speech and activity tracking and other data to analyze a pool of ALS patients in an attempt to classify subtypes of ALS and create targeted therapies.

In the early days, Coviello, Cohen and friends would sell Pickals at supermarkets and festivals the way Girl Scouts sell cookies, by setting up a table and smiling at shoppers in hopes that they’d stop to check out the wares. The business has certainly grown since then. About a year ago, Pickals launched its online sales. Daugherty sees great potential for growth. Local food shops, such as Squirrel & the Bee in Short Hills and Sobsey’s in Hoboken, carry the brand. Before his death, Cohen learned that Kings Food Market had begun selling his pickles in select locations. In September, the retailer announced that Pickals would be available in all of their stores statewide. It is worth noting that Cohen came up with the idea of Pickals as a way to help future ALS patients, rather than himself. The disease moves much faster than any research project. As Cohen’s symptoms progressed, the family moved to a more handicap-accessible house in West Orange, leaving behind the kitchen in Maplewood where Pickals began. Pickals was a gesture of good faith and of generosity. It kept Cohen busy and jovial, and continues to inspire his friends and family.

After Cohen’s death, Coviello received hundreds of messages of sympathy, including many from her husband’s photography clients—aspiring actors, up-and-coming musicians, authors, models. One message stood out in its simplicity. It mentioned that Cohen always seemed happy.

“He had a larger-than-life personality and was a very beloved figure,” Coviello said.

He also left a legacy of fun, in the form of snappy green pickles that fight ALS with humor and good cheer.

For more info on Pickals, or to order or donate online, go to pickals.org (fourjar packs are $36, six-jar packs are $54 and 12-jar packs are $108). And be sure to follow the advice shared frequently by Cohen throughout his final months: “Until further notice, celebrate everything.”