Pressing On - Applejack's History in New Jersey

Standing overgrown and abandoned alongside Route 24, Nesbitt’s mill had long intrigued Raymond Nadaskay. As a member of Mendham Township’s Historic Preservation Committee, he wondered how the mill could be saved from further decay. As an architect and entrepreneur, he also contemplated the various ways that the building, which he assumed was a gutted shell, could be put into residential or commercial use. Those musings gave way to resolve on the day he was invited to look inside the mill. “I saw a great big vat on my left, another vat on my right. I looked up on the next floor and I saw two presses,” Nadaskay says. “Everything was there. When they walked away from [the mill], they just left it. Nobody took anything.” That visit set into motion a multi-year effort by Nadaskay and others to restore the mill and create a living museum dedicated to the production of New Jersey’s most renowned intoxicant: applejack.

From Grist Mill to Cider House

When John Ralston Nesbitt headed to work on November 21, 1904, it is unlikely he had any sense that this would be the final day of operation for the grist mill that he and his mother had built in 1848. Thanksgiving was only a few days away and a warming trend undoubtedly eased the prospect of working in the unheated mill. After climbing to the top floor, however, his history of heart trouble overtook him and there, one day shy of his 86th birthday, he died. With his passing, the mill ceased the processing of local flour and feed—a once-common industry that was being undercut by the easy transport of Midwestern grain.

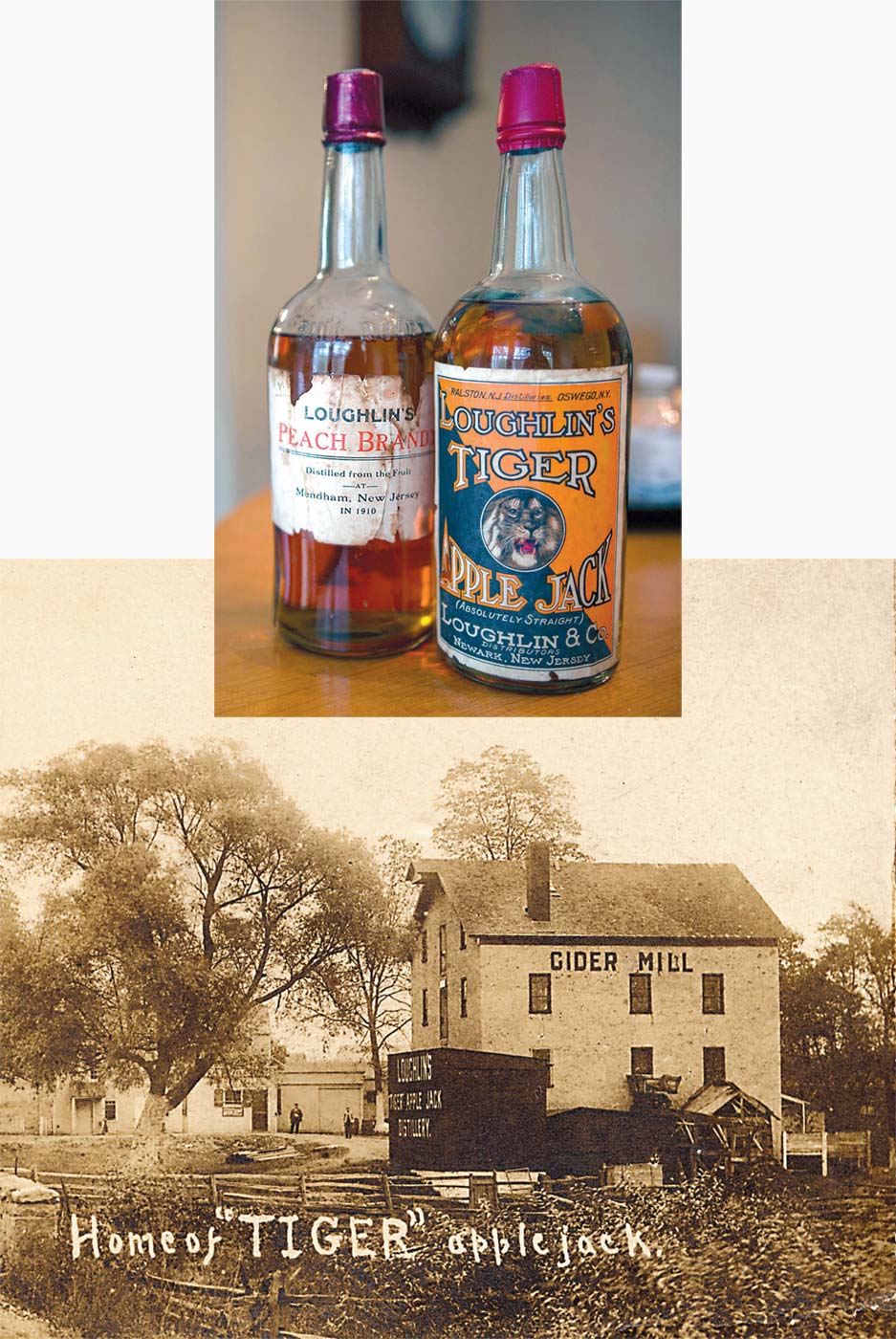

Thomas J. Loughlin purchased Nesbitt’s mill in January 1905. A liquor wholesaler from Newark, Loughlin had been leasing a distillery at the Thompson farm on Hilltop Road in Mendham since 1899. For several years prior to taking on that lease, Loughlin had purchased the entire annual applejack output from Thompson’s distillery—presumably to bottle for resale. According to patent filings, he began labeling his product “Tiger Apple Jack” in 1901. Consumers’ thirst for applejack had grown dramatically throughout the 1800s and, in 1904—one of the best apple years ever seen in our state—New Jersey was on track to produce an estimated 1 million gallons of the spirit (see sidebar, page 29).

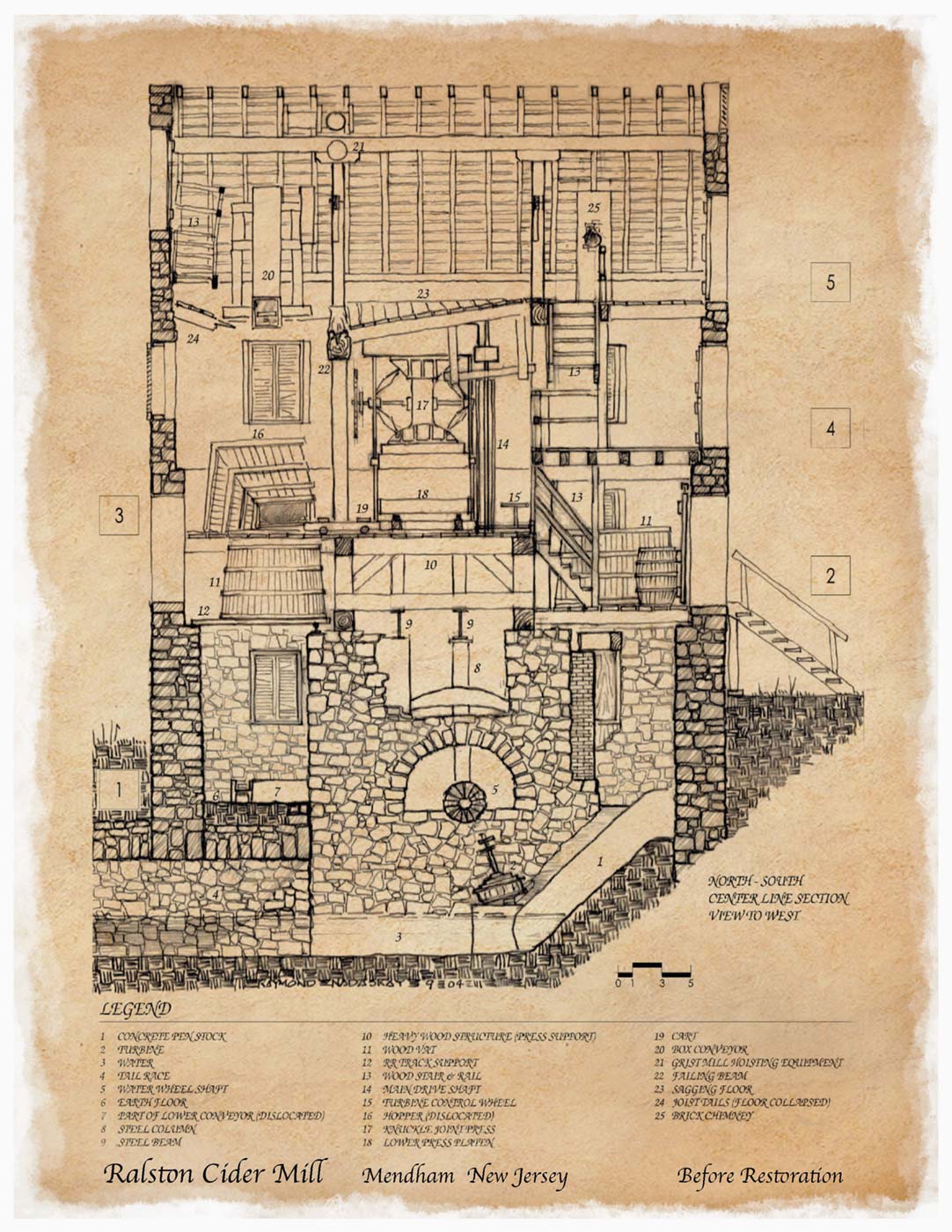

Before Loughlin could move his distillery into Nesbitt’s mill, the mill had to be converted from grain grinding to cider production— the first phase in making applejack. After working with only a single knuckle-joint press at the Thompson distillery, the move allowed Loughlin to add an additional, more efficient screw press, which increased his cider-pressing capacity from 500 gallons a day to over 2,000 gallons.

Once Loughlin’s conversion was complete, local farmers could dump their apples near a washing pit from which a conveyor carried the fruit to the top floor of the mill. There the apples were fed into a grater installed into an opening in the floor. The ground apples (pomace) dropped onto a platform below that held a five-foot-square lattice rack topped with a four-inch-deep wooden form over which a large cloth was draped. Once that form was filled, the cloth was folded over the pomace to create a bundle and the form was removed. A new lattice rack was then added on top of the bundle and the process was repeated. When stacked with five or six bundles, the entire platform could be rolled down a track and directed to either the knuckle joint or screw press, which sat on opposite sides of the mill. With this design, another stack could be built while the first stack was being pressed, enabling continuous pressing.

As the presses bore down on the pomace, juice flowed into enormous wooden vats that sat on the floor below. When no more juice could be extracted, the spent pomace was dumped out of a chute onto the ground below and the platform was rolled back under the grinder for reloading.

Much of the weight of the massive machinery was borne by the grist mill’s thick stone walls and heavy oak timbers. Repurposed railroad tracks were added to support the four heavy vats that held the fresh cider during the early stages of fermentation. That cider was then pumped to larger fermentation vats, which sat in a shed Loughlin built alongside the roadway. Once fermentation was complete, the cider was pumped to a still where it was distilled into applejack.

From top: apples going into grinder, raking pomace, placing pressing cloth on frame

AS THE PRESSES BORE DOWN ON THE POMACE, JUICE FLOWED INTO ENORMOUS WOODEN VATS THAT SAT ON THE FLOOR BELOW.

Powering the Business

The siting of Nesbitt’s mill along a well-traveled road provided prime visibility for the “Loughlin’s ‘Tiger’ Apple Jack Distillery” sign painted onto the roadway-facing side of the vat shed. The siting also gave Loughlin access to an abundant and renewable source of power: Burnett Brook.

Nesbitt powered his two sets of heavy grindstones with a 16-foot wooden waterwheel, mounted inside the mill basement. Although steam engines were widely available, Loughlin kept the mill’s water- powered system, but replaced the waterwheel with a more efficient cast-iron water turbine. The flow of water to the turbine was controlled by a metal gate in an upstream dam. When opened, water flowed through an underground wooden pipe and into the mill basement where it was directed into the turbine. The spinning of the turbine set into motion a cog-and-gear configuration that turned the drive shaft, which provided power to the belts, pulleys, and gears that ran Loughlin’s presses, grinder, conveyor, and pumps. The water flowed back into Burnett Brook where it was used again to power other mills downstream.

Applejack’s popularity attracted considerable fraud, and adulterated products undermined the market for pure applejack. These concerns were reflected in Loughlin’s advertisements—in which he claimed to be the largest applejack distiller in the country. His taglines of “The drink of our Forefathers,” “As Old as the Hills It’s Made In” and “Distilled in a pot still in the old-fashioned way by one who knows how” played on the ideas of authenticity, tradition, and craftsmanship. Other Tiger advertisements emphasized the health benefits of applejack as a tonic of “unequaled medicinal value.” This seems to be a direct response to the Temperance Movement’s vocal assault on alcohol as a menace to public health.

(left) Fresh cider from pressing; (right) Sammy Fornaro, Jr.

A Hidden Enterprise

As Prohibition became inevitable (see sidebar, page 30), Loughlin moved his still into a hidden basement below a shed attached to the mill. To hide the tell-tale smoke from the still fire, he ran the chimney pipe up through the basement ceiling into a large pot-bellied stove on the floor above. In that way, curious law enforcement officers who opened the shed door would see the stove and assume it was the sole source of the smoke that could be seen exiting the shed via the stovepipe.

After distillation, the illegal applejack was run through an underground pipe into a free-standing garage, which was designed so that the presence of a basement could not be detected from outside the building. The applejack was bottled— most likely without barrel aging—and then brought up into the garage via a hidden trap door. A truck parked in the garage could then be loaded in secrecy and driven out.

After Loughlin’s death on July 3, 1920, the mill was purchased by George DuBucs, a native of France, then residing in Queens, NY. It is unknown whether DuBucs distilled applejack during the time that he owned the mill. But it is known that a popular speakeasy operated just across the road from the mill. And the obituary recounting DuBucs’ brutal mangling in the mill’s machinery on February 3, 1930, confirms that he was continuing to press cider—the home fermentation of which had not been banned. DuBucs’ widow sold the mill to Sam Fornaro Sr., who continued to press cider there until around 1938. At some point, he converted the mill from waterpower to electrical power.

Sammy Fornaro Jr. was a child during the final years of Prohibition. Yet he quickly pushes back on claims that his father distilled illegal applejack—insisting that the still was already gone when the family took over the mill. He is less strident about whether or not his father served applejack in the speakeasy across the street, which he also owned—and which he turned into Sammy’s Ye Olde Cider Mill restaurant after Prohibition.

Archival rendering: courtesy of Raymond Nadaskay

THE RESTORATION BEGAN WITH CAREFUL DOCUMENTATION OF THE EXISTING STRUCTURE TO UNDERSTAND THE MILL’S CONSTRUCTION AND TO FIND CLUES, SUCH AS WEAR MARKS AND STAINS, THAT REVEALED WHERE MACHINERY HAD BEEN PLACED.

Ruin & Revival

No longer a working distillery, the mill’s interior slowly began to succumb to the inevitable damage of disuse, seeping water, and time. A visitor to the mill in the 1950s reported that a family of raccoons had taken up residence in the old apple hopper. And so the mill remained, fate undetermined, until Nadaskay’s visit, which eventually led Fornaro to sell the mill to Mendham Township in 2004 and to the formation of a nonprofit to oversee its restoration and operation as a museum.

After years of research and rebuilding by historians, archeologists, millwrights, and others, the Ralston Cider Mill stands as the sole functioning historic hard cider mill in a state that was once home to hundreds of applejack distilleries. Although rotted timbers, worn out belts, and missing bearings needed to be remade, the mill is not, Nadaskay emphatically points out, a re-creation. “I want to stress that we didn’t remake anything,” he says. “It took a long time to figure out where certain things were, but it’s all original. Nothing is made up. There is no conjecture.”

The restoration began with careful documentation of the existing structure to understand the mill’s construction and to find clues, such as wear marks and stains, that revealed where machinery had been placed. The building was then stabilized, and the machinery was restored to working order.

Fornaro’s memories of seeing the mill in operation also helped the millwrights piece together its configuration. “They hired two millwrights from upstate New York,” Fornaro explains. “They would come down on Mondays, work on the mill and go home on Friday. Every Tuesday I used to come down and they would have paper written as to ‘what was here and how did that look?’ I tried to tell them from my memory and they replaced everything the way it was—or very close to it.” Fornaro also animated the mill’s history with childhood memories, such as riding up the apple conveyor with his sister and watching farmers arriving in wagons and trucks to take the discarded pomace home to use as livestock feed.

In fall 2008, the power to the drive shaft was turned on and the Ralston Cider Mill whirred to life for its first public demonstration of early 20th century apple pressing technology. Since that day, fall tours, evening lectures, school field trips, troop outings, and annual pressing days have given thousands of visitors lessons in the technology of waterpower and the elegant simplicity of mill engineering, as well as the experience of seeing firsthand the inner workings of an industry once central to our state’s economy and identity.

Archeological surveys located the foundation of the vat house, miller’s house, and scale house where farmers’ trucks were weighed before and after unloading their fruit. The long-range plan is to rebuild those structures in order to create a more complete picture of a working applejack distillery.

Ralston Cider Mill is a testament to the determination of Nadaskay and other historic preservationists who understand the educational and inspirational value in providing working examples of historic technology and craftsmanship.

“The passion part of it hit that first day,” Nadaskay says, “and it never went away because every time we would do something there, it was a new discovery.”

THE RALSTON CIDER MILL STANDS AS THE SOLE FUNCTIONING HISTORIC HARD CIDER MILL IN A STATE THAT WAS ONCE HOME TO HUNDREDS OF APPLEJACK DISTILLERIES.

With the help of tour guides, visitors can understand the Ralston Cider Mill through multiple lenses, such as renewable energy and adaptive reuse. In the Visitor Center, they can learn about the complicated history of alcohol taxation and control. And by observing and contemplating Nesbitt’s decisions about where to site and how to power his mill, visitors can get a clear picture of what it means to have a place-based business that is deeply embedded into the local landscape and fully participating as an integral, vital component of a local farm economy.

Archival photo: courtesy of Ralston Cider Mill

A BRIEF HISTORY OF APPLEJACK MAKING IN NJ

Applejack is an effective method of preserving apples, and intensifying the kick of hard cider. It was also once an important part of New Jersey’s local farm economy— giving farmers a market for excess and damaged apples, including those knocked off of trees by windstorms.

Although also made in other states, applejack has always been identified as a New Jersey product. In 1834, our state had 388 cider distilleries. Seventy years later, according to an article in the Jersey City News, the output of applejack in New Jersey was estimated to be 1 million gallons. Known also as cider brandy, cider spirits, and Jersey Lightning, applejack was produced all over the state, with the product of Morris County enjoying a reputation for fine quality.

Applejack is made by distilling hard cider and then barrel aging it, typically in charred oak. Historical accounts differ on the optimal aging time, with five years being frequently cited.

Traditional farmstead applejack, however, was made by leaving a barrel of hard cider outside in the depth of winter to allow the action of freezing—partial thawing—refreezing to eventually separate the hard cider into an alcohol- filled heart encased in a body of ice. A hot poker was then pushed through the ice and the alcohol was drawn off. The colder the winter, the higher the resulting alcohol.

This method produced a more potent drink than hard cider, though not as strong as distilled applejack. The freezing method also resulted in epic hangovers, and chronic consumption could lead to a condition known as apple palsy. That is because freezing did not remove the methanol, acetaldehyde, and fusel oils—toxic impurities that can be removed or lessened by distillation. —F.M.

PROHIBITION IN THE GARDEN STATE

The legal production of applejack ended in New Jersey on September 8, 1917, with the passage of the Food and Fuel Control Act, which banned the wartime use of food crops in the production of distilled spirits. This paved the way for the 18th Amendment, which was passed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and ratified by the requisite 36 states on January 16, 1919.

The Volstead Act defined the process by which the 18th Amendment’s ban on the manufacture, sale, and transport of intoxicating liquor would be enforced. The Act defined “intoxicating” as anything over .5 percent alcohol and set the date for the implementation of Prohibition as January 17, 1920.

New Jersey was the last state to ratify the 18th Amendment and Prohibition did not enjoy widespread public support in the state. In the 1919 governor’s race, which became known as the Applejack Campaign, the winning candidate, Edward I. Edwards, identified himself as being “as wet as the Atlantic Ocean” and vowed to fight against enforcement of the law. Although Prohibition-era newspapers ran stories of raids on New Jersey applejack stills, Colonel Ira Reeves, federal Prohibition administrator for New Jersey, calculated that fewer than one-half of 1 percent of the state’s bootleggers ever got caught.

Noting that New Jersey was considered one of the wettest states in the nation and deeming Prohibition laws unenforceable, Reeves summed up the outcome of his work in our state this way: “After months of the most strenuous effort—doing my office duties during the day, raiding at night, often working eighteen hours a day for two or three weeks at a time—I took inventory of what had been accomplished. I had raised the price of alcoholic beverages and reduced the quality.”

New Jersey was one of the first states to ratify the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment. Prohibition, the so-called “Noble Experiment,” officially ended on December 5, 1933.

RALSTON ANNUAL APPLE PRESSING DAY: SATURDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2021

You can visit the Ralston Cider Mill on fall weekends to tour the building, learn the history, and see the machinery in action. But it is only at the Annual Apple Pressing Day that you become immersed in the full sensory experience—the pervasive aroma of apples, the rhythmic click-whir-hum of mill machinery at work, the steady drip of apple juice and the determined buzz of yellow jackets claiming their share of the harvest.

A team of volunteers is required to process the truckload of apples that is donated each year by Alstede Farm in Chester. As volunteers work, visitors get to see every aspect of the process— from apple washing through to the collection of freshly pressed juice. Along the way, guides explain the pressing process and the mechanics of the mill.

The 2021 Annual Pressing Day will be held Saturday, October 23. General admission is $15. Visit the Ralston Cider Mill website for Pressing Day details and updates. All other fall 2021 weekend visits require an appointment, which can be made on the website. —F.M.

Ralston Cider Mill

336 Mendham Road West

(Route 24), Mendham, NJ

ralstoncidermill.org