New Jersey Winemakers Embrace New Options Including One Ancient Technique That’s New Again

There’s been a welcome shift in the way U.S. wine drinkers perceive sparkling wine. Where it was once thought of as a special-occasion sipper, it’s now enjoyed every day, suitable for both toasting a newly married couple and pairing with Tuesday night dinner. Where there was once an impression that anything that wasn’t French Champagne was lesser than, there’s now the understanding that quality sparkling wine can come from anywhere around the world.

Along with this changing appreciation for bubbles, wine drinkers are embracing all types of wine made using older techniques that employ less manipulation during production. Some wine drinkers choose them because of the idea that they are healthier for both people and the planet. Others enjoy them because they’re looking to experience new styles that are fresh with intriguing characteristics and flavors.

The shifting perception of bubbles and the trend of making wine using older methods has created the perfect opportunity for an ancient style of sparkling wine—older than even Champagne —to make a worldwide comeback. There’s a handful of New Jersey wineries bottling this ancestral fizz known as pét-nat.

What is Pét-Nat?

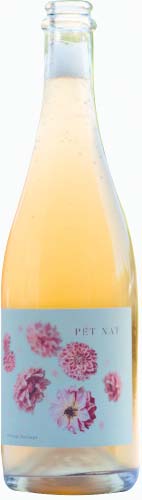

Pét-nat, short for pétillant naturel, is a French term that is best translated “naturally sparkling.” It’s sometimes referred to as the methode ancestral (or ancestral method). It is, most likely, the original method of making wine with bubbles.

Champagne, as well as other sparkling wines made in the Champagne—or traditional— method, is produced by bottling wine that has already gone through a first fermentation. The winemaker adds more yeast and sugar to the bottle, caps it off, and lets the yeast turn the sugars into carbon dioxide until a million or more bubbles are trapped in the bottle. Eventually, the cap is taken off, the yeast removed, and a cork quickly inserted.

Winemakers produce pét-nat by putting wine that has not yet finished its first fermentation into bottle, capping it, and letting it finish fermentation in the bottle. The wine becomes something that is always bubbly, often cloudy, sometimes funky (beer drinkers who enjoy sours and saisons often like the wine), and—depending on your personal taste—refreshingly delightful.

It’s the way sparkling wine was produced before the Champagne method was perfected, a method that created more stability in the bottle. Modern bottle- making techniques have taken care of the stability issue; glass is now strong enough to stand up to the pressure of sparkling wine.

“WITH PÉT-NAT, YOU’RE CAPTURING A FERMENTATION— THE YEAST AND WHAT THEY CAN DO.”

Capturing Fermentation

Vinifying grapes using the pét-nat method creates the possibility for an entirely new experience from versatile grapes.

“Usually, the goal of wine is to capture soil and climate in a certain year, a moment in time and place,” says Kevin Bednar, winemaker at William Heritage Winery in Mullica Hill, the first winery in the state to make pét-nat. “With pét-nat, you’re capturing a fermentation—the yeast and what they can do.”

Wine enthusiasts who pride themselves on picking out grapes in a blind wine tasting may find their finely honed sniffing, swirling, and sipping skills useless when identifying the grapes in a glass of pét-nat. The process often masks the telltale aromas and flavors of grapes.

“You’d have to be very talented and kind of guessing to pick out the grape variety in a pét-nat,” says Bednar. “It’s a representation of fermentation versus grape variety, vineyard site, and year.”

William Heritage bottled two pét-nats from the 2021 vintage. The first was a rosé made from Cabernet Franc and Merlot grapes. The second was a white made from Chenin Blanc.

Both were made from the same base as their still (non-bubbly) counterparts. Bednar siphoned off a portion of the fermenting juice destined to be the winery’s estate still rosé and bottled it before fermentation was finished. He did the same with Chenin Blanc, stealing some of the fermenting wine that would ultimately be bottled as a still wine.

The rosé pét-nat is full of strawberry, watermelon, and pear notes. It’s dry, tart, and refreshing. But it would be difficult to home in on the Cabernet Franc and Merlot grapes from its smell and taste. The Chenin pét-nat is full of pineapple, lemon, ginger, and citrus notes, but taste it side by side with its still counterpart and the average wine drinker would have a tough time recognizing they started out as the same wine.

John Cifelli, general manager at Unionville Vineyards in Ringoes, is intrigued by how characteristics of a grape can show in a pét-nat and isn’t as positive as Bednar that grapes in the wine are unidentifiable.

“It’s interesting how different grapes express themselves in pét-nat.” he says. “Particularly with red pét-nat, [the style] shows off the versatility of the grape.

Unionville currently has two bottles of this bubbly from the 2021 vintage: a rosé and a Riesling, which is where the winery started with pét-nat.

“We grow a lot of Riesling, and since 2018 this project has allowed us to divert some of the production to a new label,” he says. “Having a fun, fresh new product instead of a glut of dry Riesling was a no-brainer. Of course, with a touch of sweetness, Riesling is a terrific grape to work with in this style of wine.”

Unionville eased into production with 50 cases the first year, available only to wine club members who came into the tasting room and gave the passphrase “farmed and fermented” to buy it.

“It was a lot of fun,” Cifelli says. “Others at the bar became curious and joined the club, and we sold all 50 cases without it ever being on the tasting sheet. From that point, we have dedicated half of our Riesling to the sparkling version.”

The winery has gone from 50 cases of the 2018 vintage to 200 cases of the 2021 vintage, and Cifelli believes the current vintage will not make it through a 12-month sale cycle.

Educating Wine Drinkers About Pét-Nat

At Unionville, where people visit with a specific interest in quality New Jersey wine, they’re likely to trust the person behind the tasting room’s bar who offers them a sample of something different. But does the general wine drinking public feel the same?

“Only about 5 percent of our guests come in looking for some kind of ancestral pét-nat,” says Christine Zubris, owner of Versi Vino, a by-the-glass wine bar, restaurant, and bottle shop in Maple Shade. While the wine bar hasn’t yet served a local pét-nat, there is always one from somewhere in the world on its list.

Between the unfamiliarity of the category, and the wine’s tendency to be cloudy—since not all pét-nats are filtered before bottling and the yeast is never disgorged from any pét-nat—many wine drinkers are skeptical.

“I always put pét-nat on a flight with other sparkling wines to make it an entrance into the space,” says Zubris. “Not until customers taste it do they become believers.” Many people end up ordering a full glass or taking home a bottle.

Even so, Zubris usually has just one pét-nat on the menu for a very practical reason: The style tends to go flat quickly.

Drinking Pét-Nat

There are significantly fewer bubbles in pét-nat than in Champagne so they dissipate more quickly. A bottle of Champagne that’s left uncorked for an hour and then closed will still have some bubbles left in it the following day. Not so with pét-nat.

“Pét-nat is capable of lasting more than a day if you stop it immediately,” says William Heritage’s Bednar. “After it’s poured, immediately put a sparkling wine stopper on to keep the bubbles.”

Todd Wuerker, winemaker and owner of Hawk Haven Vineyard in Rio Grande suggests storing pét-nat upright so the yeast settles.

“This allows you to open the bottle and get a really neat presentation,” says Wuerker, who makes several different bottles of pét-nat from all estate grapes each year. The wines fly out of their close-to-the-ocean winery between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

“You have the ability to see two different styles of wine from the beginning of the bottle to the bottom of the bottle,” he says. “You get a really nice clean, almost traditional style sparkling wine at the beginning but then as you pour it, you’re going to get more yeast, more full body, and pick up more of the lees characteristics in the wine.” Lees are the leftover, spent yeast cells in the bottle that add to the cloudiness and some of the funkier aromas and flavors that pét-nat can have.

When serving, unless you’re doing a celebratory toast, skip the tall, skinny flute glasses. Serve pét-nat in regular wine glasses to get the most of its aromas and flavors. Whichever type of glass you choose, serve it cold.

One final and important thing to know about pét-nat is to always open it away from you and over a sink or outside. The bubbles can burst forth from the mouth of the bottle when the cap is removed, causing a bit of a mess.

PÉT-NAT–PRODUCING WINERIES IN NJ

There are only six New Jersey wineries currently producing pét-nat. Note that the style is produced in small quantities and often sells out quickly.

BELLVIEW WINERY

150 Atlantic St., Landisville

bellviewwinery.com

BENEDUCE VINEYARDS

1 Jeremiah Lane, Pittstown

beneducevineyards.com

HAWK HAVEN VINEYARD & WINERY

600 S. Railroad Ave., Rio Grande

hawkhavenvineyard.com

SHARROTT WINERY

370 S. Egg Harbor Rd.

(Rt 561), Blue Anchor

sharrottwinery.com

UNIONVILLE VINEYARDS

9 Rocktown Rd., Ringoes

unionvillevineyards.com

WILLIAM HERITAGE WINERY

480 Mullica Hill Rd., Mullica Hill

williamheritagewinery.com

SPARKLING AT THE START

The history of sparkling wine in the Garden State reaches back to the 1860s when French immigrant Louis Nicolas Renault—who came from a family of French coopers (barrel makers) in Champagne—planted vines in Egg Harbor. Before Prohibition, Renault was the largest producer of Champagne in the United States. At the Paris Exposition in 1900, judges awarded Renault’s Champagne a gold medal.

Prohibition put an end to New Jersey’s dominance in the sparkling wine category, but these wines are once again bubbling up in the state. Wineries are producing various styles of fizz that wine lovers can open for a celebratory toast or for a Tuesday night dinner, although it’s now rare to see these wines labeled as Champagne in New Jersey or any other U.S. wine region.

An early 2000s trade agreement made it illegal for U.S. wineries to call their sparkling wines “Champagne,” reserving that designation strictly for wines made in the famous French region. U.S. wineries, including Renault, already bottling wine with a Champagne label before the agreement may still use the word.

A SAMPLING OF NEW JERSEY’S OTHER BUBBLES

Traditional Method Sparkling Wine

(made similarly to Champagne)

Tomasello Winery Blanc de Blanc Brut

Tomasello Winery Rkatsiteli

William Heritage Winery Estate Reserve Blanc de Blanc

Hawk Haven Vineyard Estate Brut

Sharrott Winery Brut

Old York Cellars Sparkling White

Charmat Method Sparkling Wine

(made similarly to prosecco)

Hopewell Valley Vineyards Bramante made with Brachetto D'Acqui and Moscato Bianco

Hopewell Valley Vineyards Spumante Secco made with Moscato and Glera

Amalthea Cellars Dream Barrel Sparkling Chardonnay

Piquette

(made by rehydrating grape pomace with water and adding sugar to ferment)

Sharrott Winery Blaufrankisch Piquette

Beneduce Vineyards Aqua Pazza