New Jersey’s Wine Industry has Grown Up— and it’s Poised for an Exciting New Era

The view was spectacular and the wine was delicious.

The year was 2007 and I was standing high on a hillside in Warren County, looking down upon rows of lush vines bursting with grapes. A picturesque stone barn served as tasting room and wine cellar; in the fields, a farmer’s work was under way. A “city girl” at the time, it was not lost on me that the spot where I stood was equidistant between New York City to my east and Philadelphia to my south, a mere 70 miles in either direction. To me, it was paradise.

I fell in love with New Jersey wines that day at Alba Vineyard, and it’s been an ongoing love affair ever since. I’ve had the good fortune to linger on the patio at Auburn Road Vineyard and Winery to watch the sunset with a glass of wine and plate of cheese. I’ve reveled in the wine, music, and sunshine of Unionville Vineyard. I’ve shared wine talk in tasting rooms at Hawk Haven, Bellview, Terra Nono. In my role with Edible Jersey, I’ve had countless NJ wine experiences the past 15 years and, along the way, I’ve seen an industry in growth mode.

New Jersey’s wine industry gets more exciting each year, continuously expanding with possibilities, excellence, and expertise. From our view, it’s poised to enter a new era and now, more than ever, is the time to understand, support, and experience it.

A Sip of History

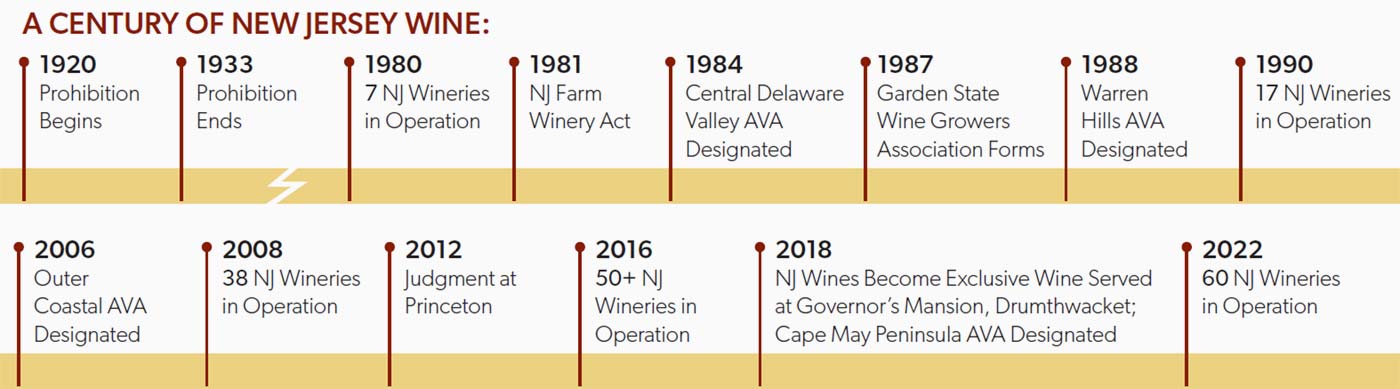

Grapes have been grown and wine made in New Jersey since Colonial days, but the industry came to a near standstill with the start of Prohibition in 1920. Except for a few wineries, such as Renault in Egg Harbor City, which received a dispensation to produce wine for church or medicinal purposes, many vineyards were left fallow or turned over to other crops during the long 13 years of Prohibition.

Its repeal in 1933, however, far from guaranteed the return of a wine industry. First of all, it can take years to prepare soil for growing a particular crop again and farmers had to weigh the investment of time and money to return to winemaking.

Adding to the difficulty was the fact that, post-Prohibition, NJ lawmakers were slow to relax laws regulating the production and sale of alcohol. State legislation regarding alcohol remained complex, especially in comparison to other states, such as California, New York, and Oregon. For nearly 50 years following Prohibition, New Jersey allowed only one winery license per million residents. The near impossibility of obtaining a license meant that, as of the early 1980s, New Jersey was home to only seven wineries.

Things finally began to change in 1981 with the passage of the New Jersey Farm Winery Act, first of several efforts by the NJ legislature to loosen the hold of Prohibition-era restrictions. The new legislation permitted NJ farms with at least three acres of grapes to produce and sell wine. As a result, the number of wineries in New Jersey more than doubled by the end of the ’80s and continued to rise throughout the ’90s.

Still, growing grapes and making wine is a long-term commitment. New vineyard plantings often require three to five years before yielding a suitable crop and another one to three years of aging prior to sale.

Judgment of Princeton: Recognition for a Nascent Industry

Due to the industry’s slow reboot post-Prohibition, NJ wines remained far under the wine world’s radar for years, even as the number of wineries increased. It takes time for grape-growing, harvest, and winemaking practices to become consistent in terms of quality and there was little momentum on the marketing front for decades. That all began to change substantially with an event in June 2012 that proved to be one of the first major acknowledgements of the quality of NJ wines.

The “Judgment of Princeton” was modeled after a 1976 blind tasting called the “Judgment of Paris” that rocked the wine world when several California wines famously trounced top French wines from Bordeaux and Burgundy. Held during an American Association of Wine Economists conference at Princeton University, the Judgment of Princeton was spearheaded by journalist George Taber, who had been a part of the Paris match-up decades earlier and wrote a book about the experience.

“George became a believer in the quality of New Jersey wines in 2007-12,” recalls Lou Caracciolo, founder of Amalthea Cellars Winery in Atco, who hosted a series of tastings with Taber during those years where NJ wines “went head-to-head with the best of Napa” and stood up very well.

At the Princeton match-up, NJ wines were pitted against vintages from many of the same estates that had participated in the Paris event, including renowned labels such as Chateau Mouton-Rothschild and Haut Brion. At the end of the judging, rankings showed Chardonnays from New Jersey’s Unionville, Heritage, and Silver Decoy (now Working Dog) wineries among the top four picks against the French White Burgundy wines, an outstanding showing. Although the French won the Bordeaux category, NJ reds from Heritage, Tomasello, Bellview, Silver Decoy (now Working Dog), and Amalthea Cellars performed extremely well.

The results of the Princeton competition garnered NJ wines long-overdue recognition for their quality. Equally important, NJ wines now had the attention of wine writers and afficionados.

“The Judgment of Princeton was every bit as consequential to us as its counterpart in Paris was to California all those years ago,” says Scott Donnini, owner of Auburn Road Vineyards in Pilesgrove. “It meant that we had to be taken seriously…. There was no longer a rational basis for excluding the Garden State from consideration when discussing serious wine growing regions of the world.”

A Booming Market

A decade after the Judgment of Princeton, the New Jersey wine industry appears to be in full throttle. “New Jersey is now home to more than 60 wineries with 20 more in the pipeline,” says Devon Perry, executive director of the Garden State Wine Growers Association.

The number of grape varieties grown in New Jersey has also been on the rise. There are now more than 80 varieties of grapes grown throughout the state, including Pinot Noir, Riesling, Cabernet Sauvignon, Blaufränkisch, Chardonnay, Sangiovese, Albariño, and many more. The industry continues to benefit from research and technical support provided by Rutgers University and its Cooperative Extension agents.

“There is clearly growth ahead,” says Perry. “In the 10 years since the Judgment of Princeton, we have seen a tremendous amount of development as well as the desire to elevate fine wines in the state.”

New wineries, expanded tasting rooms, more retail outlets, initiatives such as the Winemakers’ Co-op, and the establishment of winery trails and wine festivals have made it easier for more consumers to experience Garden State wines first-hand. In 2018, Governor Phil Murphy and First Lady Tammy Murphy announced that NJ wines would now be the only wines served at the Governor’s mansion at Drumthwacket. The pandemic also proved to be a boon of sorts as it brought many first-time visitors out to local wineries to enjoy their scenic, expansive (and safe) outdoor experiences.

As the industry grows, so does the opportunity. New Jersey is a mega-market for winemakers. Home to nearly 9.3 million people, New Jersey ranks 11th in the nation in population, according to the 2020 U.S. Census. It also ranks 6th in the nation for wine consumption, with an estimated 33 million gallons of wine consumed each year in the Garden State. Less than 3% of the wine currently consumed in New Jersey, however, hails from NJ grapes. When one considers that 85% of all domestic wines sold in the United States comes from California, the opportunity becomes even more clear.

“We’ve got tremendous momentum in the Mid-Atlantic,” says Perry, referring to NJ’s location at the epicenter of a regional market that includes New York and Philadelphia. “We provide an accessible ‘wine country’ experience right in their backyards. Here, you can meet the owners and develop relationships [with winemakers] that are very unique.”

What’s Next

The Garden State Wine Growers Association (GSWGA) and Perry, who was appointed to her role in March, have a variety of plans to keep that momentum going. New Jersey Wine Week in November will feature the awarding of the annual Governor’s Cup; a new Ambassador program will involve consumers, media, and other interested individuals with Association initiatives. A Wine Growers Select program, whereby three wine selections from each winery will be chosen for recognition by fellow winemakers and other experts, will soon debut.

A new marketing campaign is in the works, “Fall in Love with New Jersey Wine Country,” and destination and hospitality recommendations will be added to the Association’s popular app so that “visitors and residents have a really nice resource for exploring the state,” says Perry.

Planning has also begun for the first New Jersey Restaurant and Wine Week to be held in 2023, matching NJ wines with high-end culinary experiences.

“The goal is to celebrate and elevate the finely grown products and people of the New Jersey wine industry,” says Perry. “They are award-winning, multi-generational vintners and we want to associate them more with the media and culinary partners in the Mid-Atlantic. After all, we are one tank of gas away from about 33 million people.” Still, as she looks to the opportunity beyond New Jersey’s borders, Perry knows loyalty begins at home.

“We’ve learned in a period of great economic uncertainty that our industry works very well in the State of New Jersey as a collaborative force. I’m most excited about New Jersey falling in love with NJ Wine Country, and being as proud of it as we are.”

To learn more about New Jersey wines and download the GSWGA app, visit newjerseywine.com.

IT STARTS IN THE SOIL

From north to south, the terrain and growing conditions vary greatly within our small state, but much of New Jersey is relatively well-suited to grape growing. Thanks to our climate, soil, elevation, and other geographic characteristics, New Jersey is home to four American Viticultural Areas (AVA), a federal designation given to regions identified as beneficial to grape growing. New Jersey’s AVA regions include Warren Hills AVA, Central Delaware Valley AVA (shared with portions of eastern PA), Cape May Peninsula AVA, and the Outer Coastal Plain AVA.

There are approximately 200 AVAs in the United States, and NJ’s Outer Coastal Plain AVA, established in 2006, is among the top 10% nationally in terms of size, encompassing 2.25 million acres in south Jersey and currently home to approximately 20 wineries. The region, located between the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay, earned its AVA designation due to its relatively flat, low hills and sandy, well-drained soil, all characteristics considered favorable to grape growing.